Summary:

U.S. healthcare is transitioning from fee-for-service to value-based care, emphasizing quality, cost-effectiveness, and innovations like telehealth, HaH, and PCC.

HALM CORE CONTENT:

2.3 Healthcare trends and barriers across the continuum of care (e.g., extended care, acute hospital care, ambulatory care, home care)

2.4 Non-traditional settings and methods to improve access

2.4.1 Hospital at Home

2.5 Patient-centered care

2.8 Telehealth impact and other emerging technologies

2.9 Value-based care models

2.9.1 ACOs

2.9.2 Bundled payment models

2.9.3 Clinically integrated networks

2.9.4 Co-management agreements

2.9.5 MIPS/MACRA

2.9.6 The transition from volume to value-based care implementation

CASE SCENARIO:

A 72-year-old man with a history of obesity, chronic kidney disease stage 3b, heart failure, osteoarthritis with significant degenerative changes in both of his knees, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia wants to change his primary care physicians. He chooses a primary care physician who is part of an accountable care organization. His new physician assesses his medical conditions and starts a regimen for treatment of his knee pain with different medications, physical therapy, and a weight-loss program.

After six months, the patient’s knee pain persists, and the physician refers the patient for an orthopedic evaluation. The decision is made to have a knee replacement. The patient undergoes total knee arthroplasty and is sent home from the hospital after two days with his regular medications as well as home physical therapy, home health to monitor his cardiac status, a course of anticoagulation administered regularly by the patient and his caregiver, and a device to monitor his vital signs and post-operative recovery including increasing ambulation and flexibility exercises in his home.

With mounting pressures from rising costs, uneven health outcomes, and increasing consumer demands for higher-quality care, the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) model in the United States is challenged. In response, the U.S. healthcare ecosystem has been shifting in fits and starts with care innovation across care environments. Payment innovation has accompanied operational innovation, with value-based care (VBC), better aligning reimbursement with high-quality, cost-effective care.

Access and the Contemporary U.S. Healthcare Landscape

Although many individuals in the United States have health insurance, there are still barriers to access; the complexity in using healthcare coverage is one obstacle.(1) Long wait times for appointments, difficulty finding in-network physicians, and transportation all may lead to care delays.(2)

While hospitals retain a prominent position in U.S. healthcare, only 8% of the U.S. population had an overnight hospital stay in 2018.(3) This is counterbalanced by a vast amount of outpatient activity with more than 1 billion office visits annually in the United States.(4) Notably, there are also shifts in post-acute and long-term care. More than 68,000 post-acute and long-term care providers cared for 7.3 million individuals, according to the 2020 National Post-acute and Long-term Care Study.(5) Care innovation is necessary in each of these domains to improve outcomes, quality, and effectiveness.

Hospital at Home

The concept of hospital at home (HaH) allows patients to receive hospital-level care in their homes. This includes daily physician or nurse visits, monitoring of vital signs, laboratory testing, intravenous (IV) fluid and medication administration, and hospital transfer if needed. This care is supported by advanced medical technologies and multidisciplinary teams. The model has gained interest due to its ability to improve outcomes and patient satisfaction while reducing healthcare costs.

HaH’s origins can be traced to early 20th-century healthcare delivery when house calls and care in the home were standards of practice. Even with the expansion of hospitals after the Hill-Burton Act, at-home care continued for less intensive needs.

Burton and Leff tested a HaH model in the 1990s.(6) They demonstrated that acute care at home for older adults resulted in better patient outcomes and lower costs compared to traditional hospitalization. The COVID-19 pandemic created a watershed moment for HaH care. Hospitals with overwhelming capacity constraints adopted HaH to manage non-COVID and low-acuity COVID-19 cases. CMS also launched the Acute Hospital Care at Home program in 2020, allowing hospitals to bill Medicare for HaH services. This, combined with greater trust in home-based care, has driven more acceptance of HaH.

HaH COMPONENTS

HaH programs comprehensively screen patients with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria that include clinical stability, home safety, and caregiver availability.(7) Patients who may benefit from HaH include those with pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations, heart failure, cellulitis, or infections that require IV antibiotics.

A standard HaH care team includes physicians who oversee patient care via telehealth and in-home visits, advanced practice professionals (APPs) such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants, and nurses who provide in-person care, administer medications, monitor clinical conditions, and identify necessary social support services. HaH teams also may include pharmacists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, or dietitians.

Improvements in technology have fortified HaH, with remote patient monitoring (RPM) and telehealth making it easier to monitor patients, perform HaH virtual consultation, and communicate with patients and caregivers. In addition to intensive care coordination and individualized care plans, HaH requires that teams bring testing equipment into the home for laboratory and imaging studies. HaH models also facilitate home delivery of medications, durable medical equipment, and supplies.

HaH programs have protocols to escalate care and transfer the patient to a hospital if needed. They partner with social services to support patient needs such as transportation, food security, or home safety. HaH programs also educate patients and caregivers about clinical conditions, treatment, and emergency protocols.

The CMS Acute Hospital Care at Home program has a list of requirements for HaH programs, including compliance with the Condition of Participation standards for hospitals, daily assessment by the physician in-person or via telehealth, twice-daily evaluation by a registered nurse or paramedic, immediate connectivity to a nurse if needed, a 30-minute response time for a decompensating patient, and data submission to CMS. Regulations also may vary by state in APP scope of practice, coverage for certain services, and whether home health licensing is necessary.

HaH TODAY AND TOMORROW

The benefits of HaH make a compelling case for its expansion. HaH has reduced the cost of care by 38% with fewer laboratory and imaging tests and consultations compared to inpatient hospitalization according to one study.(8) HaH patients also had increased levels of activity and decreased readmissions.

Based on early experience with the Acute Hospital at Home waiver, complex patients receiving HaH had 0.5% mortality during HaH and lower mortality compared to similar patients who were hospitalized with a lower readmission rate as well.(9,10) Such data continue to support expansion of HaH and evolution in the capabilities of the teams that deliver it.

Patient-Centered Care

Demographic shifts in the U.S. population are reflected in greater diversity in opinions, languages, and culture in the population. As such, clinicians must individualize their care more than ever to make it equitable and patient-centered. Patient- or person-centered care (PCC) integrates the values, beliefs, and preferences of the patient in shared decision-making as an acknowledgment of patient autonomy.(11) This leads to a plan of care that is appropriate and acceptable for the patient. PCC enhances patient satisfaction and is associated with decreasing admissions, readmissions, and length of stay in various studies.

One often-seen tension is the pull between evidence-based practice and PCC. One multicenter analysis noted that organizations with strong improvement-oriented cultures, accountability, and regular, meaningful staff engagement were more likely to provide evidence-based clinical care and effectively incorporate patient and family preferences in developing and implementing the plan of care, reducing that tension.(12)

IMPLEMENTING PCC

PCC requires a commitment to transformation. While there is no definitive PCC playbook, insights from a qualitative study suggest seven domains are critical for PCC in any organization: leadership, patient and family engagement, staff engagement, a focus on innovation, alignment of staff roles and priorities, synchronization of organizational structure and process, and a caring environment.(13)

As value-based care has matured, PCC is now recognized as an important, although not yet dominant, quality measure. The alignment of PCC and VBC is complicated by the paucity of applicable patient experience and preference measures, and cost calculations that are payer- instead of patient-focused.

Strategies have been proposed to align PCC and VBC, including using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in clinical trials, general practice, and in value calculations, and purposeful integration of patient preference in clinical decisions and guidelines. As care innovation advances, organizations will likely need to incorporate PCC and PROMs more extensively to inform feedback related to clinical care and operational decisions.

Telehealth and Emerging Technologies

Although telehealth emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic, its history is actually decades old. NASA and the Nebraska Psychology Institute piloted closed-circuit television for remote monitoring and consultation in the 1960s.(14) Programs such as Project ECHO in New Mexico developed simultaneous specialty care and educational uses for telehealth platforms.(15)

Today, telehealth is an essential element of care delivery. Digital cameras and wearables assist telehealth with real-time imaging and biometric measurement. Telehealth can also support remote robotic surgery, intensive care unit capabilities, behavioral healthcare, and diagnostics in teleradiology and telepathology.

Post-COVID-19, telehealth continues to be a means of healthcare access, although its use has declined for some; 48% of all Medicare beneficiaries were telehealth users in 2020, and 24% were telehealth users in 2023 based on Part B claims.(16) It is interesting to note demographic differences in telehealth adoption among patients. Telehealth use has been lower among individuals who lack insurance coverage, among young adults, and among residents in the Midwest compared to other parts of the United States.(17) CMS recognized the importance of telehealth by adding a number of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for telehealth services that have been updated annually.

Remote patient monitoring has been adopted as a component of telehealth in various clinical settings, be it inpatient, outpatient, or at home. RPM interventions based on measured data have been integrated into COPD and heart failure management, post-operative care for patients’ status-post arthroplasty, neonatal care, home and remote cancer care, diabetes management, home dialysis, and most recently, COVID-19.

Combining RPM with patient education has a positive effect on patient outcomes. CMS and commercial payers have acknowledged the increasing relevance of RPM with reimbursement for a set of RPM CPT codes. The 10-fold increase in RPM use for Medicare beneficiaries since COVID-19(18) suggests there is expanding interest in using RPM to enhance patient care.

Accountable Care Organizations

The term “Accountable Care Organization” was introduced by Elliott Fisher and colleagues at Dartmouth in 2006. They envisioned ACOs as groups of providers, including hospitals, physicians, and other caregivers, who would take collective responsibility for a defined population’s care with shared clinical and financial accountability and quality measurement. Section 3022 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 created the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP). This program encouraged healthcare organizations and physicians to form ACOs to manage and be accountable for the care of Medicare beneficiaries.

ACOs have continued to evolve since their inception, with payers adopting ACO principles in VBC contracts and CMS bringing new models forward, such as the Pioneer ACO Model, which tested more advanced ACOs, and the Next Generation ACO Model that allowed for greater financial risk and reward. ACOs now include physician-led, hospital-based, and integrated delivery system ACOs. In 2022, more than 11 million Americans were receiving healthcare through 1,000-plus ACOs in the United States.

ACOs have met with headwinds even as they have grown in number.(19) Some organizations have struggled to meet savings targets or manage downside risk in advanced models. Hospital ACOs can experience misalignment with incentives. Coordinating care across diverse providers can be logistically challenging. Critics also argue that ACOs may not sufficiently address social determinants of health. CMS has recognized many of these factors in new ACO models.

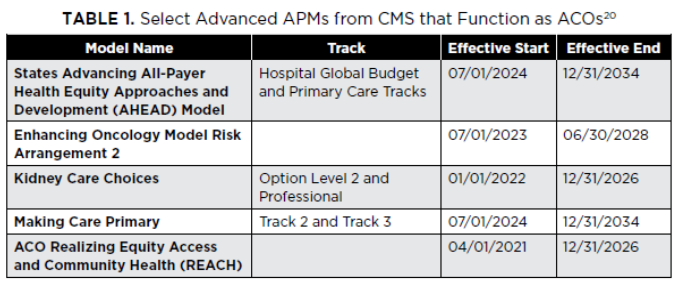

CMS continues to adjust the ACO model as one of several advanced alternative payment models (APMs) (see Table 1). There are newer specialty-care ACO constructs, such as the Enhancing Oncology Model and Kidney Care Choices models, and, recognizing potential shortcomings of primary care-focused ACOs, CMS created the States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development Model (AHEAD Model) and the ACO Primary Care Flex Model.

The AHEAD model collaborates with states to decrease healthcare costs, improve population health, and advance health equity. The ACO Primary Care Flex Model is designed to increase program participation for low-revenue ACOs and rural providers. It features a prospective payment option and a one-time payment to cover administrative costs.

ACOs have delivered more than $21 billion in total savings since they started, including $4.3 billion in Medicare savings in 2022 with 69% of ACOs achieving shared savings in the last performance year.(21) Research indicates that ACOs have resulted in modest improvements in quality, although they have leveraged care plans, home visits, clinician-specific data, and care coordination for medically complex patients far more frequently than non-ACO organizations.(22)

Bundled Payments

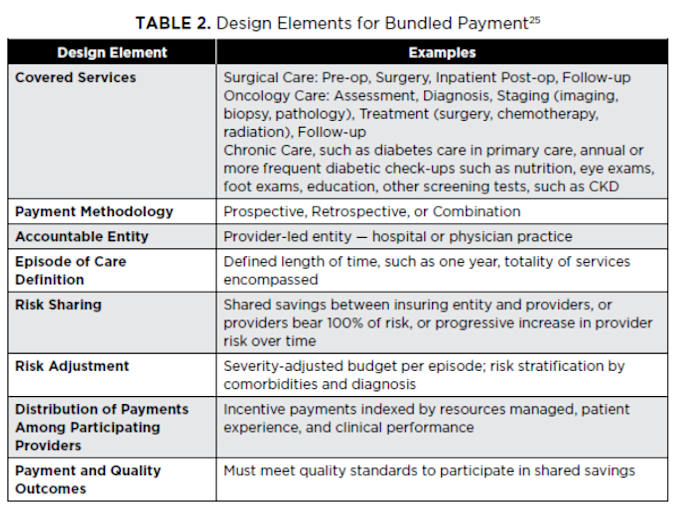

Another form of APM is bundled payment. These payment models incentivize providers to deliver coordinated, high-quality care by offering a fixed payment for an entire episode of care, covering all services provided during that period (see Table 2). Bundled payments gained attention initially in the 1980s and 1990s. The Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Demonstration (1984–1989) provided bundled payments for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgeries, covering hospital and physician services. It demonstrated cost savings and maintained quality.

Bundled payment models expanded at the start of the century with large employers, such as Walmart and Lowe’s, and employer coalitions partnering with health systems to negotiate bundled payment contracts for high-cost procedures, such as joint replacements and certain cardiac procedures. The ACA formalized bundled payments as part of payment reform, and CMS launched the three-year Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration. This demonstration covered all Part A and B services for 28 cardiac and nine orthopedic inpatient surgical procedures and services.(23)

This heralded a series of additional initiatives that included the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) from CMS. This encompassed four payment models covering 48 clinical episodes.(24) The Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement was released as a mandatory model in 2016, along with BPCI Advanced as a voluntary model. Certain design elements are integral for bundled payments.

It is essential to define an episode of care, which includes all related care services, such as diagnostics, treatments, hospital stays, rehabilitation, and follow-ups, within a specified time frame, usually 30 or 90 days. Episodes can be related to procedural (e.g., joint replacements, cardiac surgery), acute (e.g., pneumonia, myocardial infarction), or chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes management).

Payment is a single negotiated amount paid to cover all services within the episode. The models that determine payment can be prospective — payment is made up front and distributed among the providers involved in the bundle — or retrospective — providers are reimbursed fee for service initially and total costs are reconciled against the bundled payment after the episode. Providers may share in savings if costs are less than the bundle price or absorb losses if costs exceed them.

To be effective, bundles require significant collaboration across the episode care continuum (e.g., hospitals, physicians, post-acute care facilities). Care pathways or standardized protocols for the episode ensure consistent, evidence-based care. A review of 20 studies confirmed that bundled payment maintains or improves quality of care while lowering costs for total joint replacement.(26) However, for other conditions or procedures, data showing improvements was less consistent.

CMS has added a new model to better assess the effectiveness of bundled payment: the Transforming Episode Accountability Model (TEAM). TEAM bundles payments for lower-extremity joint replacement, hip and femur fractures, CABG, spinal fusion, and certain abdominal surgical procedures.(27) TEAM as a mandatory model is also designed to address health equity and incorporate regional pricing. Hopefully, TEAM will yield data that can establish the true effectiveness of this care innovation.

Clinically Integrated Networks

Clinically integrated networks (CINs) grew out of a trend of vertical integration in healthcare in the early part of the 21st century. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) defines a clinically integrated structure as a joint contracting program that includes:

Independent contracting, especially if payers and the network cannot agree on terms.

Price setting only for services that are part of the clinically integrated program.

Sharing of substantial financial risk in the arrangement by all physician participants.

No unnecessary exchange of pricing information.

No assistance in the refusal of or restriction of physicians in contracting with payers.(28)

There are three main types of CINs: a joint venture physician-hospital organization, a subsidiary or subsidiaries of a health system, or independent practice associations (IPAs).(29) In general, CINs can withstand FTC scrutiny if they demonstrate:

Active participation by physicians in developing and operating the CIN.

Shared goals of quality, efficiency, decreased utilization, and lower costs.

Processes for reviewing clinician performance and removing inefficient clinicians.

Development and implementation of evidence-based clinical guidelines.

Use of interoperable health information technology to ensure care integration.

A nonexclusive network.

Restricted access to provider pricing data.

Healthcare systems view CINs as a lever to increase their breadth of clinicians and services across multiple settings, thereby improving population health and negotiating leverage with payers.

Organizations that have successfully created large CINs have developed common clinical protocols, expanded quality measurement, and increased meaningful performance feedback to clinicians.(30) They also have realized efficiencies by co-locating practices and driving health information exchange across electronic health record (EHR) platforms.

Still, there is limited information regarding the actual performance of CINs. CINs do appear to have met or exceeded many of their goals of care related to reducing utilization, managing clinical conditions, and improving patient experience. The inherent challenge with such reporting is that comparisons are often against internal data or generalized CMS data. Nonetheless, CINs appear to have staying power as aggregators of physicians and clinical services.

Co-Management Agreements

The most traditional example of co-management is a hospital contracting with a physician group to co-manage a service line. Another example is an arrangement between providers to co-manage different aspects of patient care. A specialist may provide surgical care and then refer the patient back to their primary care provider for post-surgical monitoring.

When co-management aligns a hospital and physicians, those physicians can focus on improving quality and efficiency in that service line in exchange for compensation payable by the hospital. These arrangements can cover one hospital or an entire health system and can be applied to any service line such as orthopedic surgery, cardiology, or maternal care. By increasing efficiency, reducing waste, and increasing profitability, co-management agreements have “legitimate business and medical purposes.”(31)

There are two types of co-management arrangements. The first is direct contract co-management in which the physicians are individually engaged or engaged as a group. The other model is the limited liability company (LLC) model. In the LLC model, the hospital contracts with a management company, the LLC, formed to co-manage the service line. This LLC can be wholly owned by the physicians or jointly by the physicians and the hospital.

In both constructs, fees are paid as hourly- and performance-based services. Hourly-based services are administrative, such as clinical workflow improvements, scheduling, oversight of other clinicians in the service line, credentialing, patient case management, materials management across the service line, program development, and medical staff committee service and leadership.

Performance-based services are clinical in nature and focus on achieving pre-determined quality outcomes for the designated service line. Performance-based compensation is variable in that, based on service line performance, physicians may receive any compensation amount from $0 up to a maximum incentive amount consistent with fair market value (FMV) by a third-party valuation firm.

There are important guardrails to consider when establishing or reviewing a co-management agreement.

Does the arrangement satisfy a legitimate business need of the parties?

Is the referring party the best or only party to deliver the services for the need?

Are the services (and fees) tailored and limited so that there is no question about their purpose and intent?

Would the arrangements be reasonable if no referrals were received?

Successful co-management agreements improve clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, service line efficiency, and effectiveness. These agreements help physicians retain autonomy over their practice and provide an avenue for them to share in financial rewards of strategically aligned programs. Hospitals benefit from the focus on quality and cost and have a legal protection through such constructs in providing performance-based incentives. There is little published data evaluating co-management agreements, likely due to their distribution and application across different environments.

MIPS and MACRA

The merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) are milestones in transforming Medicare payment models. Prior to MACRA, Medicare physician reimbursement was largely determined by the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. The SGR, however, required annual congressional interventions to avert reductions in payment.

MACRA repealed the SGR formula in 2015, with an intent to end the annual cycle of fiscal adjustments to physician payment. It also established a framework for transitioning from volume- to value-based reimbursement through the MIPS and alternate payment models (APMs). The legislation simplified existing quality programs, rolling them into MIPS, and provided incentives for participation in APMs, which involved more risk-sharing but offered greater potential rewards.

MIPS consolidated the physician quality reporting system (PQRS), value-based payment modifier (VBM), and CMS EHR Incentive Program, known as “Meaningful Use,” into a single performance-based payment system with four categories:

Quality (45% of the MIPS score): Performance across quality measures, including patient outcomes, practice improvement, and guideline adherence.

Cost (15% of the MIPS score): Cost-efficiency of care, including total cost of care during the year or a specific episode of care.

Improvement Activities (15% of the MIPS score): Efforts to improve practice, such as care coordination, patient engagement, and health equity.

Promoting Interoperability (25% of the MIPS score): The use of certified EHR technology.

Providers with high MIPS scores earn positive payment adjustments funded by penalties for lower-scoring providers, creating a budget-neutral system.

APMs offer a separate pathway to accept financial risk and accountability for patient outcomes. Providers participating in qualifying APMs are exempt from MIPS and receive a higher Medicare conversion factor update, +0.75% versus +0.25%, beginning in 2026 while also being eligible for model-specific performance payments. APMs also include a separate lump sum incentive payment that expires at the end of the 2024 performance year and the requirement that participants meet a threshold percentage of payments or patients through qualifying APMs.

These thresholds scale up in the 2025 performance year, making it more difficult to be a qualifying provider. APMs include ACOs (see Table 1) as well as other payment structures, such as BPCI-Advanced, the Maryland Total Cost of Care (TCOC) Model—Care Redesign Program, and the concluding Vermont Medicare ACO Initiative.

CMS is not the only entity supporting and evaluating APMs. Several states and payers have APMs as well, including episode-based payment, Medicaid APMs, and second-generation patient-centered medical home tracks.

Data regarding the impact of these programs are mixed. For instance, MIPS scores do not necessarily correlate with performance, as seen in a study of more than 80,000 primary care physicians.(32) Physicians with low MIPS scores had worse performance on diabetic eye examinations, hemoglobin A1c screening, and mammography screening compared to physicians with high MIPS scores. However, physicians with low MIPS scores had better performance with regard to influenza vaccination and tobacco screening. Interestingly, physicians with low MIPS scores and better patient outcomes cared for more multimorbid and vulnerable patients.

The Ongoing Shift from Volume to Value

The transition from volume to VBC in U.S. healthcare requires a fundamental shift in how medical services are delivered and reimbursed. Changes in reimbursement have been essential with VBC to overcome FFS inertia. The ability of these care innovations and payment models to effect change is predicated upon:

Improvements in data quality and delivery.

Analytics and population health management tools that make it easier to identify, communicate with, and treat at-risk patient groups.

Workflow changes combined with technology that makes it easier to engage in evidence-based practice.

Physician leadership for the culture shift necessary for team-based PCC.

By prioritizing value, the U.S. healthcare system aims to achieve the “Triple Aim”: better patient experience, improved population health, and reduced per capita costs. With the right tools and more financial alignment, it may even improve clinician engagement and access to resources for all patients, supporting the parameters that now define the Quadruple and Quintuple Aims as well.

Chapter Summary

Multiple areas of care innovation are occurring simultaneously with shifts in reimbursement in the United States. As healthcare organizations adjust to incorporate the innovations that will work best for their patients, they also continue to examine and create structures that can allow them to deliver care more broadly with greater alignment across services and physicians.

Excerpted from Healthcare Administration, Leadership, and Management (HALM): The Essentials, First Edition (American Association for Physician Leadership, 2025).

References

Levitt L, Altman D. Complexity in the US Health Care System Is the Enemy of Access and Affordability. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(10):e234430. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.4430

Telesford I, Winger A, Rae M. Beyond Cost, What Barriers to Health Care Do Consumers Face? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. August 22, 2024. Accessed November 20, 2024. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/beyond-cost-what-barriers-to-health-care-do-consumers-face/#Percent%20of%20adults%20who%20delay%20or%20did%20not%20get%20health%20care,%20by%20type%20of%20care,%202022 .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2019 Summary Tables. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2019-namcs-web-tables-508.pdf .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Table P-10a. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2019 Summary Tables. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2018_SHS_Table_P-10.pdf , retrieved November 11, 2024.

Lendon JP, Caffrey C, Melekin A, et al. Overview of Post-acute and Long-term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2020. In: National Health Statistics Report 208. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; August 27, 2024. Accessed November 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr208.pdf .

Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at Home: Feasibility and Outcomes of a Program to Provide Hospital-Level Care At Home for Acutely Ill Older Patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(11):798–808. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00008. PMID: 16330791.

Kanagala SG, Gupta V, Kumawat S, et al. Hospital at Home: Emergence of a High-Value Model of Care Delivery. Egypt J Intern Med. 2023;35:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-023-00206-3 .

Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital Level Care at Home for Acutely Ill Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;172(2):77–85. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0600 .

Levine DM, Souza J, Schnipper JL, et al. Acute Hospital Care at Home in the United States: The Early National Experience. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177(1). https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-2264 .

CMS. Fact Sheet: Report on the Study of the Acute Hospital Care at Home Initiative. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services News Release. September 30, 2024. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-report-study-acute-hospital-care-home-initiative .

Institute of Medicine. Toward Health Equity and Patient-Centeredness: Integrating Health Literacy, Disparities Reduction, and Quality Improvement: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009.

Engle RL, Mohr DC, Holmes SK, et al. Evidence-based Practice and Patient-Centered Care: Doing Both Well. Health Care Manage Rev. 2021;46(3):174184. https://doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000254 . Epub 2019 Jun 24.

Bokhour BG, Fix GM, Mueller NM, et al. How Can Healthcare Organizations Implement Patient-Centered Care? Examining a Large-Scale Cultural Transformation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2949-5 .

Anawade PA, Sharma D, Gahane S. A Comprehensive Review on Exploring the Impact of Telemedicine on Healthcare Accessibility. Cureus. 2024;16(3):e55996. https://doi:10.7759/cureus.55996 .

Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. Outcomes of Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection by Primary Care Providers NEJM. 2011;364:2199–2207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009370.

CMS. Medicare Telehealth Trends Report. Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. July 15, 2024. Accessed December 2, 2024. https://data.cms.gov/sites/default/files/2024-09/c213a5e9-9e70-4b46-b5f1-2fb941ea0f6c/Medicare%20Telehealth%20Trends%20Snapshot%2020240827_508.pdf .

Lee EC, Grigorescu V, Enogieru I, et al. Updated National Survey Trends in Telehealth Utilization and Modality (2021-2022). ASPE Office of Health Policy Issue Brief. April 19, 2023. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/7d6b4989431f4c70144f209622975116/household-pulse-survey-telehealth-covid-ib.pdf

Parikh H, Tarosky A, Maglione A. OIG Report Recommends Increased Oversight of Medicare’s Reimbursement for Remote Patient Monitoring (RPM). Nixon Peabody Insights. October 8, 2024. Accessed December 2, 2024. https://www.nixonpeabody.com/insights/alerts/2024/10/08/oig-report-recommends-increased-oversight-of-medicares-reimbursement-for-remote-patient-monitoring ,

Khullar D, Schpero WL, Casalino LP, et al. Accountable Care Organization Leader Perspectives on the Medicare Shared Savings Program: a Qualitative Study. JAMA Health Forum. 2024;5(3):e240126. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.0126.

Quality Payment Program. 2023 and 2024 Comprehensive List of APMs. QPP. December 26, 2023. Accessed November 12, 2024. https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/document/3ad0ec11-dc16-4af0 -8a98-ddd8b8ae660f.

CMS. Performance Year Financial and Quality Results. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2023. Accessed November 22, 2024. Accessed November 22, 2024. https://data.cms.gov/medicare-shared-savings-program/performance-year-financial-and-quality-results .

Bao C, Bardhan IR. Measuring Value in Health Care: Lessons from Accountable Care Organizations. Health Affairs Scholar. 2024;2(3):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/hasschl/qxae028

CMS. Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/ace

CMS. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative General Information. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/Bundled-Payments

Struijs J, de Vries EF, Baan CA, et al. Bundled Payment Models Around Work: How They Work, and What Their Impact Has Been. The Commonwealth Fund. April 6, 2020. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/bundled-payment-models-around-world-how-they-work-their-impact .

Agarwal R, Liao JM, Gupta A, Navathe AS. The Impact of Bundled Payment on Health Care Spending, Utilization, and Quality: A Systematic Review. Health Aff. 2020;39(1):50–57. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.201900784 .

Shashikumar SA, Ryan AM, Maddox KEJ. Medicare’s New Mandatory Bundled-Payment Program—Are We Ready for TEAM? NEJM. 2024;391(22):2065–2067. doi.10.1056/NEJMp2410850.

Schaff MF, Anderson GD. The Nuts and Bolts of Establishing a Clinically Integrated Network, Las Vegas, NV. November 2015:American Health Lawyers Association, Physicians and Hospitals Law Institute, Accessed February 17, 2025, http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/345447/file-2402958872-pdf/HORNE_The_Nuts__Bolts_012315.pdf?t=1422568193753 .

Hart J. Clinically Integrated Networks. The Business of Primary Care. Accessed February 17, 2025, https://www.thebusinessofprimarycare.com/articles/clinically-integrated-networks .

Ridgely MS, Timbie JW, Duffy E, Wold LJ, Buttorff C. Consolidation by Any Other Name? The Emergence of Clinically Integrated Networks. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(Suppl 1):114. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13493

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Re: OIG Advisory Opinion No. 12-22. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. January 7, 2013. Accessed December 4, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/advisory-opinions/658/AO-12-22.pdf .

Bond AM, Schpero WL, Casalino LP, Zhang M, Khullar D. Association Between Individual Primary Care Physician Merit-based Incentive Payment System Score and Measures of Process and Patient Outcomes. JAMA. 2022;328(21):2136–2146. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.20619.

Topics

Quality Improvement

Action Orientation

Financial Management

Related

The Collaboration Imperative: Why Healthcare Executives Must Unite Against an Existential ThreatWhy Big Companies Struggle to Negotiate Great DealsA Clinical Care Pathway to Provide Value-Based Care to Patients Hospitalized with CHF, COPD, and Pneumonia