The Institute of Medicine’s landmark report To Err Is Human(4) catalyzed a movement to reduce preventable harm in healthcare systems. In response, researchers have focused not only on clinical interventions, but also on the science of teamwork, exploring how interdisciplinary collaboration affects patient outcomes.(5) Healthcare’s complex, interdependent nature renders it a powerful environment in which to explore and apply team theory. Models derived from business, military, and aviation sectors have frequently informed healthcare applications.(5)

Cross-Functional Teams: Lessons from Other Industries

In business, cross-functional teams (CFT) — defined as groups with diverse professional expertise collaborating on a shared objective — are often deployed to drive innovation and solve complex problems.(6-9) Specifically, these are groups of 6–14 individuals from different work areas within an organization and ideally from different levels of organizational hierarchy. Broadly, the concept relies on diversity of perspective from members, enriching the understanding of the problem and streamlined solutioning because of broad engagement.(3)

In healthcare literature, however, the term “cross-functional” is often used synonymously with “interdisciplinary,” referring instead to teams of diverse clinicians working toward clinical goals.(10) Regrettably, business-like applications of cross-functional methodology are underutilized and insufficiently described in healthcare literature.(3) An abundance of non-peer-reviewed articles espouse CFT merit but offer little description for their implementation.(1,2) Adding to disorganization, medical education often lacks specific business and innovation content, creating inexperienced physician leaders with little exposure to alternative innovation methodologies.(11)

Emerging physician leaders long for actionable guidance to advance the quality agenda.(12) This manuscript presents a real-world application of a CFT methodology. Key physician leadership insights and practical considerations are shared to inform the implementation of future CFTs specifically within healthcare.

Project Overview and Team Formation

In early 2024, a CFT was established at a regional health center in Barrie, Ontario, to address the challenge of inpatient emergency department boarding (IEB). The topic and scope were predefined by the hospital senior leadership team (SLT) and approved by the board of directors before project initiation. The CFT was formed by, and accountable to, the hospital CEO and vice president of quality, risk, and patient experience.

The initiative was supported by dedicated funding for a six-month full-time secondment for all CFT members, excluding the physician member, who was supported at 0.4 full-time equivalent. The team was expected to deliver strategic recommendations by the end of the term; implementation, however, remained the responsibility of the SLT to ensure alignment with broader organizational priorities.

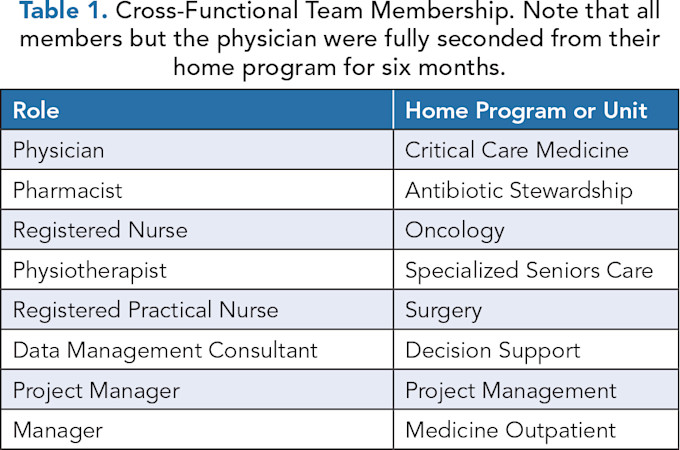

Member recruitment was conducted via an open call to all hospital staff, with efforts made to ensure diverse representation, independence from ED operations, and absence of employee performance concerns. Prior quality improvement training was considered an asset. In total, eight members were selected, see Table 1.

Leadership Enablers and Critical Considerations

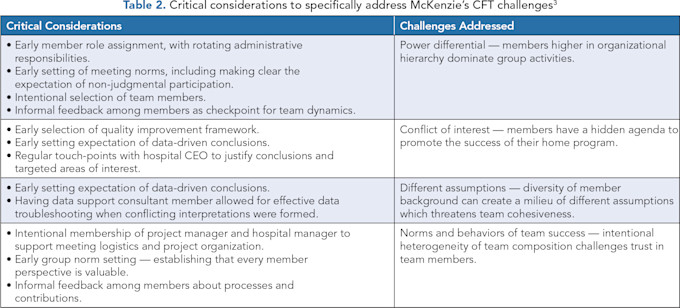

Upon project completion, CFT members specifically identified key processes or contributors to success and outlined key learnings, as described herein. See Table 2 for critical considerations specifically addressing McKenzie’s CFT challenges.(3)

Early Scope Definition and Norm-Setting

Early agreement on project scope, goals, and exclusion of recommendation implementation planning allowed the team to maintain focus. It is important for the seamless and productive functioning of any group, and thus critical to set group norms at the beginning. These included formal, outright selection of meeting times, description of assignment expectations, and creation of a safe space for open discussion.

Ground rules for meetings and collaboration norms further supported psychological safety and efficiency, pillars of the cross-functional framework. Routine administrative tasks, such as preparing minutes, chairing meetings, and contacting partners, were shared equally among members. Several members specifically sought feedback related to productivity and team dynamics from each other at regular intervals.

Infrastructure and Resource Support

The hospital provided comprehensive support, including technology (laptops, monitors, webcams), workspace, and travel funds. These logistical enablers, often overlooked, were vital to ensuring team functionality and continuity. Virtual and in-person work was supported.

Protected Time for Team Members

The time required to garner a holistic understanding of nuanced healthcare issues should not be underestimated. Our group spent the better part of four months building a sense of hospital-specific contexts. Time-consuming activities, such as frontline job shadowing, were critical for understanding actual processes and fostering credibility among frontline staff. It is the opinion of this group that the resulting engagement and workshopping of recommendations were far more impactful. Social capital was leveraged when recommendations directly affected these individuals.

Importantly, team members were fully seconded from regular duties to allow focused engagement. This time investment was essential for in-depth contextual learning, credibility-building with frontline staff, and robust partner engagement. Shadowing and on-site observations proved instrumental in developing meaningful and practical recommendations.

Regular and Active Leadership Engagement

Throughout the project, structured, one-hour biweekly updates with the hospital CEO and vice president of quality provided critical support and feedback loops. These sessions reinforced accountability, contextualized system barriers, and clarified alignment with strategic goals, including the evolving hospital strategic vision. They also allowed iterative refinement of the team’s approach and deliverables.

Preliminary conclusions and draft recommendations required clear justification. The team found this to be incredibly impactful by highlighting the need for clear data and checking member assumptions.

Visible Executive Sponsorship

Supervisor support is key to the impact of CFTs.(3) The hospital CEO played a pivotal role in promoting the project through internal communications and regional collaborations. This vocal endorsement fostered staff cooperation and helped overcome resistance from hesitant partners. In cases of low engagement, formal communication helped reset expectations. In cases of future CFT methodology, the authors recommend proactive, formal communication from the CEO to all employees outlining specific expectations for engagement, namely, a timely email reply and unbarred document sharing.

Data-Driven Discovery

Strategic and intentional data collection to support understanding of the current state was critical. CFT membership of a hospital decision-support consultant allowed for untampered access to rich hospital data with continuous and timely optimization of data reports. Rapid data synthesis and analysis occurred. Several authors have worked in previous quality improvement programs when the decision support work was done on a consultative basis, often shared among several projects. Resulting delays in communication or data reports often hindered project progression.

Moreover, the creation of a thoughtful and intentional constellation of data points is required for a full understanding of complicated healthcare processes. Specifically, this group aimed to collect and refine quantitative data, integrating insights from multiple forms and sources of qualitative data to enrich interpretation and provide a deeper understanding. Intentional diverse input from a varied audience was sought.

Sources of qualitative data included but were not limited to formal questionnaires, semi-formal small-group sessions, informal frontline engagement in the clinical setting, and targeted job shadowing. Targeted audience included all identified frontline providers involved in the process, hospital managerial and logistics staff, physicians, and patients.

Importantly, early selection of an appropriate quality improvement framework supported structured inquiry and mitigated groupthink. It must be underscored that upon conclusion, the justification of recommendations required demonstration of unbiased data interpretation. This was critical to the project’s success, as recommendation uptake would have been significantly reduced by audience prejudice otherwise.

Physician Leadership

A dedicated physician team member served as a liaison to the broader medical community, promoting medical professional engagement and ensuring medical perspectives were accurately represented. Specifically, the physician member coordinated email communication with physician leaders, led small-group and individual engagement sessions, supported networking to allow physician job shadowing, and provided perspective from the viewpoint of medical professionals. An unanticipated benefit was enhanced SLT buy-in given the physician’s credibility. This added significant weight to the final recommendations.

Intentional Team Composition and Autonomy

Essential within the CFT was a diversity of healthcare experience. This promoted rich discussion and perspective on patient flow processes. Specifically, nursing and allied health membership promoted frontline engagement during hospital ward visits and job shadowing. The group found that frontline staff were more apt to open up and participate honestly with these members.

As critical to clinical diversity was representation from appropriate non-clinicians. These non-clinicians were essential for the project and group organization. To our knowledge, this has not been previously described in CFT literature, which often focuses solely on highlighting the diversity of clinical perspectives. Specific membership of a project manager, hospital managerial staff, and data consultant supported informed, self-reliant team success. Each brought with them expertise to facilitate the logistics of the project; a CFT made solely of clinicians would not have been nearly as effective.

Team autonomy — functioning independently from existing hospital infrastructure — allowed for focused and unencumbered progress. Non-clinician team members also leveraged internal relationships to streamline data collection and partner engagement.

Conclusion: Leadership Lessons and Future Implications

Healthcare is a complex and interdependent system of processes. Adding to complexity, macro- and micro-organizational considerations must be taken into consideration when targeting a desired outcome. That is, the local environment, not limited to individuals, expertise, and patient population, must be considered and understood to optimize patient outcomes.

A CFT offers an opportunity to broaden and contextualize understanding of hospital processes by looking outside of a particular clinical locale and supporting exhaustive input and data analyses. This offers a potent model for developing holistic solutions to entrenched healthcare challenges. Success, however, requires intentional design and membership, leadership endorsement, dedicated time, and a culture that values data-driven decision-making and collaborative learning.

This manuscript describes practical insights from a lived leadership experience implementing a CFT in healthcare. The hope is to support healthcare leaders and physicians aiming to embrace this powerful methodology.

Acknowledgments: The authors acknowledge the assistance of Leslie McArthur and other members of the cross-functional team.

References

Ogle T. What Can Functional Teams in Healthcare Provide? Continued.com. July 13, 2023. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.continued.com/respiratory-therapy/ask-the-experts/what-functional-teams-in-healthcare-provide-186 .

Zambon J. Managing Cross-Functional Healthcare Teams: Navigating Collaboration for Project Success. LinkedIn. Published September 4, 2023. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/managing-cross-functional-healthcare-teams-navigating-jillian/ .

McKenzie L. Cross-Functional Teams in Health Care Organizations. Health Care Superv. 1994;12(3):1–10.

Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Vol 6. National Academies Press; 1999. PMID: 25077248

Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, Benishek LE, Thompson D, Pronovost PJ, Weaver SJ. Teamwork in Healthcare: Key Discoveries Enabling Safer, High-Quality Care. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):433-450. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000298

Morley L, Cashell A. Collaboration in Healthcare. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2017;48(2):207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2017.02.071

Atlassian. How to Build a Cross-Functional Team. Atlassian. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.atlassian.com/work-management/project-collaboration/cross-functional-teams .

Burkus D. How to Manage a Cross-Functional Team. Harvard Business Review. April 26, 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://hbr.org/2024/04/how-to-manage-a-cross-functional-team .

Lynn R. What Are Cross-Functional Teams? Planview. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.planview.com/resources/articles/lkdc-cross-functional-teams/ .

Alexander JA, Lichtenstein R, Jinnett K, Wells R, Zazzali J, Liu D. Cross-Functional Team Processes and Patient Functional Improvement. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 Pt 1):1335–1355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00421.x

Ghufran S, Mushtaq A. Business in Medicine—Part Ignored in Medical Curriculum. BMJ. 2011;343:d7556. https://doi.org/10.1136/sbmj.d7556

Digby GC, Douglas SL, Hobbs H. Strategies for Emerging Physician Leaders to Advance the Quality Agenda. Physician Leadership Journal. 2021;8(4):30–37.