Every physician experiences three career stages; each stage is associated with challenges and adventures. Unfortunately, there are no courses in medical school and postgraduate training on navigating the three stages of a physician’s career. By dividing your career into three segments and carefully managing each stage, you can look forward to enjoyment and success.

STAGE 1: AGE 20–39. TIME AND ENERGY, BUT NO MONEY

Despite the cost of an education — the average medical student graduate has more than $200K in student debt — interest in medicine has not declined, with over 50,000 applicants for half as many seats.(1) Managing the first stage of a physician’s career requires financial discipline, and unfortunately, not every medical student, resident, or fellow has had a proper education in personal finance.

We strongly recommend that physicians establish relationships with financial planners early in their careers. Such a relationship leads to years of prosperity into retirement (Stage 3). Even without formal business training, a few fundamental principles are critical:(2)

Recognize the time/value of money. Money is worth more now than later. If you have money now, you can invest in an opportunity that may not be available later. Or you can buy something now that may not be available later. Also, funds that you have now can be invested with a rate of return allowing growth of your original investment.

Invest early. For physicians just starting practice, we recommend meeting with a financial adviser and starting an early investment strategy that will grow over time. Investing early allows for the time/value of money concept to be fully realized. A simple investment of $1,000 per month over 30 years with an average return of 5% will be worth $1,150,036 because of compounding interest.

Diversify your portfolio. Markets ebb and flow over time. A diversified portfolio allows an investor to mitigate financial risk. For example, an airline stock will fall in value as fuel prices increase. Conversely, oil and gas company stock will rise in value as fuel prices increase. Investing in these stocks mitigates the risk of the other.

Understand risk and reward. Investments with a higher rate of return generally are also of higher risk. That means that over time, they are more volatile and can just as easily decrease as increase. A basic tenet of investment is that the average investor earns an average rate of return over time.

For early career physicians, the best advice is to hire a professional to help manage finances, invest early into a diversified portfolio, and minimize long-term investment risks.

STAGE 2: AGE 40–59. MONEY AND ENERGY, BUT NO TIME

Nearly every practicing physician has experienced this stage and its accompanying burnout blahs. Physicians can enhance their efficiency to have more time and more work-life equilibrium. We use the word “equilibrium” rather than “balance” because physicians work hard, and there is seldom a balance between work and life outside of our medical practices; rather, it is an equilibrium tipping toward work in the early years at the exclusion of lives outside of medicine.

Burnout has many negative consequences for physicians. Burnout can lead to depression, anxiety, chronic stress, irritability, decreased self-esteem, and even an increased risk of suicide. It is noteworthy that the suicide rate among physicians is more significant than in other professions and also higher than in the general population.(3) It is also of interest that there are higher rates of alcohol and substance use among physicians experiencing burnout.(4)

Burnout can lead to decreased job performance, increased absenteeism, and reduced enjoyment of our practices. It can also lead to increased medical errors and increased risk of a malpractice suit. Burnout will ultimately affect patient satisfaction and can damage our online reputation. This decrease in enjoyment also motivates physicians to leave the practice of medicine at an earlier age.

Finally, burnout can negatively affect our health and well-being. Burned-out physicians are at an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and other health consequences, including hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, hospitalization because of cardiovascular disorder, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, headaches, gastrointestinal disorders, and respiratory problems.(5)

Suggestions for Beating Back Burnout

Start small and make micro-adjustments that will improve your attitude toward your practice and make your situations more tolerable. For example, if you are a middle-aged physician and find entering data into the EMR daunting or emotionally painful, consider asking for a scribe to do the data entry. Additionally, software programs use AI to convert voice to text, which may eliminate the need for scribes.

If working 60-plus hours a week is difficult, consider avoiding evening and weekend calls. Of course, this will also reduce compensation.

Another suggestion is to leave your comfort zone and the boredom accompanying burnout. After one of us [NB] performed his 3,000th penile implant, he realized he was bored with the operation and missing that dopamine rush following a successful operation.

He changed his focus from men’s health to female sexual dysfunction, which is a condition in its infancy. He attended lectures and meetings on the subject. This shifting of gears allowed him to leave his comfort zone and reduce his boredom.

As another example, one of us [MJK] became a medical school dean at University of Nevada at Las Vegas at age 59, which allowed him to change his career focus.

Time-Saving Suggestions

If we had to pick one problem that affects nearly every physician, it is the abundance of administrative tasks. These tasks are usually time-consuming and they take doctors away from their focus on caring for patients. The time spent on administrative tasks is a contributor to physician burnout.

Stop doing work that doesn’t contribute to patient care. First, identify unnecessary tasks, then ask your colleagues and your staff for ideas to eliminate those tasks. For example, patients can register online before the office visit. Onboarding reduces time in the reception area to complete demographic information and the health questionnaire. Also, there should be a process that allows returning patients not to have to re-enter the same data for each visit. The streamlined workflow facilitates onboarding patients and distributing the patients in the exam room in preparation for the doctor-patient encounter.

Whenever possible, simplify and automate the login process. Automation might include using a single sign-on even at large institutions where patients might be sent to multiple hospital areas and where a single login should suffice. The technology available includes radio frequency identification or RFID and bio-identification, such as fingerprint and facial recognition.

Another process that can be simplified is extending the time intervals for password reset requirements. Consider implementing a password-keeper program. A password program also avoids the unnecessary requirement for users to reenter their username and password when already logged in to the electronic health record (EHR).

Advanced rooming and discharge protocols can be standardized to enable the staff to take on additional responsibilities, saving physicians time and reducing practices’ costs. Additional tasks include identifying screening tests and immunizations due, updating specific history components in the chart, and helping with patient education and follow-up planning.

Conducting advanced activities during patient rooming will enable the physician to spend more time directly interacting with the patient rather than focusing on these necessary elements. The augmented patient discharge process will ensure patients understand and remember their discharge instructions, improving adherence to treatment.

We also suggest using AI technology to reduce the administrative burden. A good example is using AI to assist with the prior authorization process.

Obtaining prior authorization for a patient before being seen by the physician, asking for permission for a procedure, or consent to use a prescribed medication is the bane of most medical practices. It is time-consuming and expensive, as your practice must obtain permission to provide medical care at this uncompensated time. The process can also delay the patient’s medical care. Because of the volume of prior authorizations that doctors must create, practices must hire dedicated staff to handle prior authorizations instead of investing in staff or tools to enhance patient care.

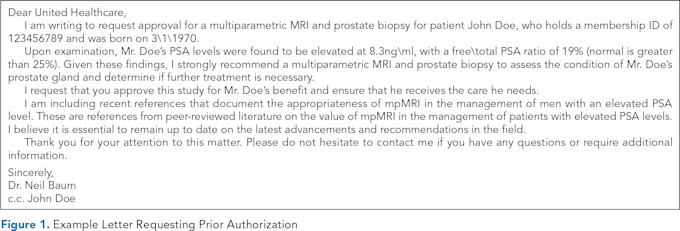

Usually, the practice will initiate the prior authorization process by completing a form and submitting it to the insurance company. This process can take from one to several hours for each PA. Using AI/GPT-4, this lengthy and cumbersome process can be reduced from one to two hours to a few minutes. Enter the pertinent patient information and the reason for the request into the text box of the GPT-4 program, and a response will occur within seconds. Figure 1 is a prompt given to United Healthcare requesting a multiparametric MRI to evaluate a rising PSA in a patient at risk for prostate cancer.

This request was faxed to the insurance company, and approval was obtained in less than 24 hours. Thus, the lengthy process involving the staff and the doctor was reduced to minutes. AI can be helpful for many other administrative and repetitive tasks that add to the excessive time that takes the physician away from providing patient care.

One of the best low-tech time-savers requiring minimal or no expense is to consider calling patients at home after a procedure or doctor-patient encounter. One of us [NB] routinely calls postoperative patients, recently discharged hospital patients, or patients who have had minimally invasive office procedures in the office.

The medical assistant or nurse prepares a list of postop patients, postprocedure patients, and recently discharged patients and informs the patients that the doctor will call between 4:30 and 6:00 p.m. The nurse requests that the patient be available for the call. This process of calling patients is usually done during drive home and takes just 10-15 minutes.

Patients report that they appreciate the call from their doctor, which reduces the number of phone calls or text messages they make to have additional questions answered. This also has a practice promotion impact on the practice when patients tell others that their doctor called them at home.

A final suggestion is to consider a career change. Change can be challenging, exciting, and rewarding. When we speak to doctors who have changed careers, we often hear a response after six months in the new job: “I should have done this sooner!” For physicians considering a career change, we recommend reading Sylvie Stacy’s 50 Unconventional Clinical Careers for Physicians.(6)

STAGE 3: AGE 60 AND BEYOND. MONEY AND TIME, BUT NO ENERGY

This third stage is when physicians start considering their exit from their practices.(7) Often, this is a difficult time for physicians who have spent 40+ years working 50–60 hours a week and suddenly have nothing to do. This situation leads to boredom, lack of exercise, poor diet, and mental health issues.

There are two certainties in life: death and taxes. To that we add another: retirement. Unless you fall dead at work, you will retire. With careful planning, the process can be easy and enjoyable. Retirement timing is usually a personal choice, usually without outside pressures. Regardless of their employment status, it’s up to the physician to decide when and how to retire.

The most common reasons for early retirement include a loss of autonomy and burnout, impacting nearly 45% of all physicians.(8) Physicians who delay retirement report doing so because of respect for their patients, a lack of interest in outside medicine, financial insecurity, and a fear of losing their sense of identity.

When considering retirement, there are two important cautions:

Don’t retire from practice too early, especially if you still enjoy your practice.

Don’t wait too long to retire because poor health — yours or your spouse’s — may prevent you from enjoying this last stage of your life.

Being a physician is often at the core of who we are, and we worry about how we will feel without the work and the status that accompanies our work. Most physicians want to retire while still healthy and enjoy physical activities such as travel. There is no magic date or time for physician retirement. Doctors spend their careers learning to diagnose and treat medical conditions and don’t receive any guidelines on when and how to retire.

When the decision to retire is made freely, as in most cases, the first issue for most physicians is, “Will I have enough money to retire?” This question is best answered by your financial adviser, whom we hope you obtained in Stage 1 of your career. If that metric is not met, then retirement must wait.

Once the financial metric is met, myriad other considerations come into play. Perhaps the most important question becomes, “Do I want to quit work?” Sure, every profession or occupation has downsides, but how many jobs can you work every day with the only goal to improve the quality of life of others? A physician provides joy and service to humanity, and you get paid handsomely for it. When you retire, you leave all that behind.

The transition to retirement can be daunting and frightening but requires planning. When physicians leave the security of the medical practice and give up a regular job, money, and prestige, it is common to go through a grieving process. However, physicians who have a retirement plan in place and execute that plan find that retirement is delightful and rewarding.

BOTTOM LINE

Considering a physician’s career as a progression through three stages around time, energy, and money is not only a helpful algorithm, but also a framework for strategizing the lifecycle of a career. Proper planning and managing expectations at each stage can lead to successful transitions at each stage and maximize career satisfaction over a physician’s lifetime.

References

The Hospital + Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania. A New Record for Medical School Enrollments. HAP News, January 13, 2025. https://www.haponline.org/News/HAP-News-Articles/Latest-News/a-new-record-for-medical-school-enrollments .

Baum N, Kahn M, eds. The Business Basics of Building and Managing a Healthcare Practice. Springer; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27776-5

Haque OS, Stein MA, Marvit A. Physician, Heal Thy Double Stigma — Doctors with Mental Illness and Structural Barriers to Disclosure. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(10):888–891. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2031013

Haas, K. Mental Health Challenges Among Physicians in the United States. Ballard Brief. 2023(3):3.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019.

Stacy S. 50 Nonclinical Careers for Physicians: Fulfilling, Meaningful, and Lucrative Alternatives to Direct Patient Care. Washington, DC: American Association for Physician Leadership; 2020.

Baum N, Mobley DF. Preparing for Retirement — Financial Readiness. Physician Leadership Journal. 2023;10(1):60–62. https://doi.org/10.55834/plj.6329641449

AMA. Measuring and Addressing Physician Burnout. AMA, July 2, 2024. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/measuring-and-addressing-physician-burnout .