The ideal configuration of coordinated care places both the patient and the provider at the center of focus.(1,2) In the current complex and disjointed healthcare landscape, patients and their families need to pay close attention to navigate various hurdles and receive the proper care without unnecessary delays. Any organization seeking to improve their care coordination services must uphold the following three fundamental principles: 1) identify a common vision with patients and their communities; 2) utilize a shared system of communication and information management; and 3) develop a structure of shared incentives and accountability. With this roadmap in mind, institutions can better serve to align the right people and technologies to promote the Quadruple Aim of improving care, health, cost, and meaning in the delivery of medical care.

Shared Vision

Clinicians can provide better treatment for their patients if they have a shared understanding of the cities and communities they inhabit together. Organizations across all economic sectors strive to improve inclusivity, but embracing cultural humility allows providers to better understand how their patients view the world and the values they should incorporate in their practice.(3) Such humility allows providers to approach patients without the notion of paternalistic superiority and to better understand problems from the point of view of the patients. To effectively treat their patients, the care team must recognize the same issues that their patients see and experience.

One way to strengthen trust with patients is to address the social determinants of health that further drive risk for adverse outcomes.

Clinicians must recognize that a single solution may not work for all groups in a community. A 2018 study through the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership compared acute care interventions (e.g., early discharge planning, patient education, medication management, and follow-up after discharge) with community interventions (e.g., utilizing a predictive model to identify outpatients at highest risk for hospitalization and deploying teams of community health workers, behavioral health specialists, and nurse care managers). Although both interventions saw positive results, some groups saw benefits while others did not; for example, researchers observed significant utilization and cost improvements for patients with Medicaid but not for those with Medicare.(4) In socioeconomically disadvantaged areas such as East Baltimore, future efforts must focus on further understanding the diverse, high-risk patient populations in these communities to best design longitudinal programs that address unmet social needs. Patients take various paths through the health system, and an effective program must move from a one-size-fits-all paradigm to a reflexive structure in which clinical decisions center around the patient.(5)

One way to strengthen trust with patients is to address the social determinants of health that further drive risk for adverse outcomes. The conditions in which people are born, grow, live, and work can directly impact physical health as well as exacerbate complex biopsychosocial processes that may not manifest until later in life.(6)The current healthcare system has not adequately connected patients to resources that can mitigate the barriers they experience as they seek care for complex medical conditions. No treatment plan can truly succeed without ensuring patients have suitable access to food, housing, employment, transportation, and many other factors often taken for granted by the healthcare system. Follow-up appointments cannot even materialize without telephones or internet access. Incorporating social determinants of health into risk stratification models can help clinicians identify high-risk patients and connect them to the proper care coordination services.(7)

Shared System

Even with aligned goals, clinicians and their care partners must have the proper infrastructure to share and respond to updated health information. The Camden Coalition, based in New Jersey, has received national attention for its work in identifying patients with very high utilization of healthcare services. One way the program identifies these “superutilizers” is through its Health Information Exchange database, which provides daily updates from EMRs at hospitals throughout the area.(8) One clear advantage of this program is the ability to monitor patients who arrive at different hospitals or institutions so that important information does not fall through the cracks. It is difficult for doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other essential care personnel to make informed decisions for a patient if their medical records and data are dispersed over multiple incompatible systems.(9)

Another example of an organization that has found success in sharing information with local partners is the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation in Dallas, Texas. This group developed software to allow food banks, homeless shelters, and other local groups to exchange information on shared patients with one another.(10) In addition to addressing social determinants of health, the initiative also benefited providers with better medication reconciliation efforts and information to help keep track of particularly vulnerable patients. Clinicians receive a better picture of a patient’s overall condition while building important relationships with community groups. The challenge in replicating these programs involves transitioning local partners from disparate, stand-alone platforms onto a shared communication network, and overcoming this barrier involves the right balance of investment and utilization of existing systems.

Shared Incentives

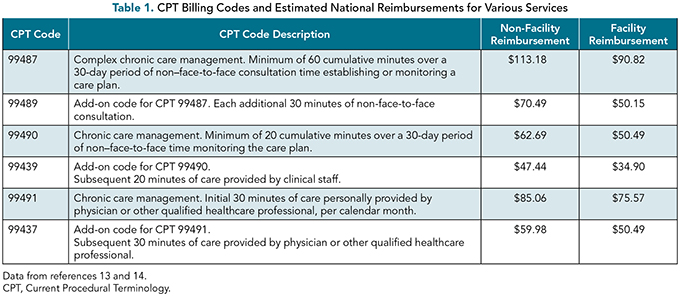

Building a successful coordinated care program with a lasting impact requires financial incentives for providers to align with the best interests of the patients. Clinical practices should take advantage of the billing codes Medicare has established for chronic care management of patients with two or more chronic conditions. Table 1 describes the CPT codes for chronic care management in greater detail. These billing codes allow clinicians to offset the costs from the initial investments required to establish a coordinated care program, and they provide opportunities to generate data on the effects of various coordination services on different patient populations.(11)

There are still issues that need to be addressed to convince more practices to embrace these programs. Because most reimbursements come from non-Medicare payers, CMS should help build the groundwork to encourage other networks to join. Higher copays, even for virtual appointments, also can dissuade patients from embracing these programs. Additionally, many chronic care management codes involve time-based billing over the course of a month, a model that may be unfamiliar to most clinicians, may not be supported by common billing systems, and may have the potential to require lots of resources to constantly monitor.(12) Ultimately, incentivizing coordinated care is an essential component of the transition toward value in medicine. Although these billing codes are fee-for-service strategies that may be viewed as preventing the transition to value-based healthcare, these codes can help different practices along their shift from volume to value while also complementing alternative payment models.

Fulfilling the Quadruple Aim

Designing a coordinated care program that brings all of these principles into alignment is no easy feat, but the benefit for patients and providers alike is unmistakable. Care coordination has been demonstrated to reduce hospital readmissions with the proper coaching and reconciliation procedures.(15) Hospitals with greater adoption of coordination and post-admission transition strategies receive higher patient experience ratings than peer institutions.(16) Despite these tangible benefits, the challenge remains in building a program that is cost-effective and secures patient buy-in.

Embracing the Quadruple Aim as a guiding light is a useful framework for creating an effective and personal care program. Initially conceived as a “Triple Aim” by Donald Berwick in 2008, the model has been expanded upon to include not only patient health and the quality of care but also associated costs and the dignity of work for providers.(17) As healthcare professionals experience increasing burnout in their practice, practices can make concerted efforts to bring joy and meaning back into the clinic through reforms that allow increased time with patients and foster close relationships with families and the rest of the healthcare team. Surveys and other metrics that measure workplace safety and engagement can be used as barometers to gauge progress on strengthening this fourth pillar. With the proper investment and mindset, care coordination can become a stronger solution for helping an aging population manage chronic conditions.

References

Compton-Phillips A, Mohta NS. Care redesign survey: strengthening the post-acute care connection. NEJM Catalyst. November 10, 2016. https://catalyst.nejm.org/strengthening-post-acute-care-connection/ . Accessed July 2, 2023.

Ansah JP, Chiu CT. Projecting the chronic disease burden among the adult population in the United States using a multi-state population model. Front Public Health. 2023;10:1082183. Published 2023 Jan 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1082183

Lekas HM, Pahl K, Fuller Lewis C. Rethinking cultural competence: shifting to cultural humility. Health Serv Insights. 2020;13:1178632920970580. Published 2020 Dec 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920970580

Berkowitz SA, Parashuram S, Rowan K, et al. Association of a care coordination model with health care costs and utilization: the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP). JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184273. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4273

Kaehne A. Care integration— from “one size fits all” to person centred care. Comment on “Achieving Integrated Care for Older People: Shuffling the Deckchairs or Making the System Watertight for the Future?” Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7:955-957. Published 2018 Oct 1. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.51

Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):19-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S206

Singer C, Porta C. Improving patient well-being in the United States through care coordination interventions informed by social determinants of health. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30:2270–2281. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13776

Finkelstein A, Zhou A, Taubman S, Doyle J. Health care hotspotting— a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:152-162. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1906848

Shull JG. Digital health and the state of interoperable electronic health records. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(4):e12712. Published 2019 Nov 1. https://doi.org/10.2196/12712

Allen A. The ‘frequent flier’ program that grounded a hospital’s soaring costs. Politico. December 18, 2017. www.politico.com/magazine/ story/2017/12/18/parkland-dallas-frequent-flier-hospital-what-works216108. Accessed March 7, 2019.

Liao JM, Navathe AS, Press MJ. Medicare’s Approach to paying for services that promote coordinated care. JAMA. 2019;321:147-148. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.19315

O’Malley AS, Sarwar R, Keith R, et al. Provider experiences with chronic care management (CCM) services and fees: a qualitative research study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:1294-1300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4134-7

Chronic Care Management Services. Medicare Learning Network. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, September 2022. Accessed July 5, 2023. www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/chroniccaremanagement.pdf

CMS. 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule: Understanding the Searchable Schedule. https://go.cms.gov/3BDnNhv .

Carter JA, Carr LS, Collins J, et al. STAAR: improving the reliability of care coordination and reducing hospital readmissions in an academic medical centre. BMJ Innov. 2015;Jul;1(3):75-80. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000048

Figueroa JF, Feyman Y, Zhou X, Joynt Maddox K. Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:844-851. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007597

Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple Aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2015;24:608-610. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160