Clinical leaders serve in critical roles within health systems. They possess system-level decision-making authority with the closest proximity to the patient, while also caring for patients themselves. Pre-pandemic empirical research identifies sound clinical knowledge, emotional intelligence, vision, and organizational behavioral skills that increase clinical leadership effectiveness.(1,2) Within primary care systems in particular, relational skills, training in process improvement, and proficiency in change management are crucial.(3) The Institute for Healthcare Improvement provides a rubric for leaders working within organizations pursuing the Triple Aim, and most recently, the Quadruple Aim: Will, Ideas, and Execution.(4) Leaders must have the will to approach each day with an improvement mindset, create an environment where ideas are cultivated from the front-line staff, and gain the resolve to execute system-level decisions, with the empowerment of local-level leadership to deliver on shared aims and goals.

There are unique challenges and rewards to clinical leadership roles. The combination of performing one’s clinical craft while providing direction and supervision involves a balancing act between the needs of individual patients, the wellbeing of staff, and the stability and continual improvement of the healthcare system. During the COVID-19 pandemic, strong clinical leadership was a powerful foundation of crisis response, communication, burnout management, and community collaboration. This article explores the unique experience and four specific lessons learned within clinical leadership in a primary care, university-based setting during the COVID-19 pandemic:

Communicating with consistency and humanity;

Being the first to try;

Attending to burnout and moral injury; and

Building bridges to strengthen responses.

Pandemic Impact on Clinical Leaders

As the COVID-19 pandemic surged in the United States, the novel coronavirus was heralded as a “landscape scale crisis: an unexpected event or sequence of events of enormous scale and overwhelming speed, resulting in a high degree of uncertainty that gives rise to disorientation, a feeling of lost control, and strong emotional disturbance.”(5)

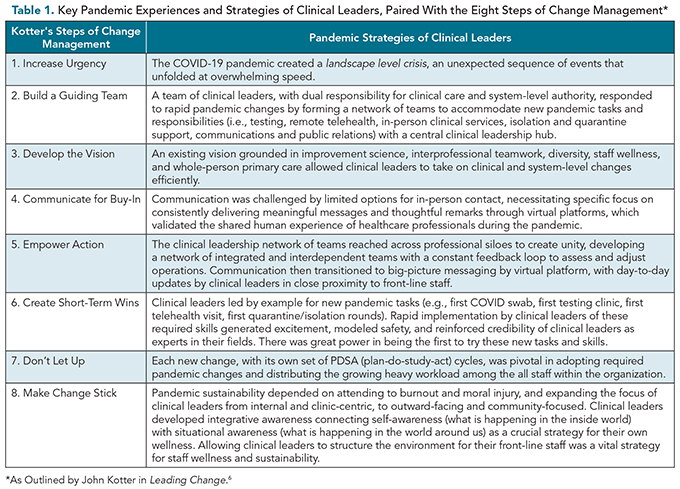

This emotional disturbance was felt deeply within healthcare systems. John Kotter’s landmark text on change management, Leading Change,(6) describes eight key steps to transformation, which is an anchoring framework from which to consider the contributions of clinical leaders during the pandemic (Table 1). Although Kotter’s text historically has been used as a framework for planned and proactive change management, we found that the skills of organizational change were brought to bear by clinical leaders during the initial crisis of COVID-19 as well as the sustained pressure for change throughout the pandemic.

This began with Kotter’s first step: Building Urgency. New telehealth technology, personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements, patient visit procedures, testing algorithms, and isolation and quarantine guidelines were all changes that required urgent, rapid-fire implementation and immediate uptake by healthcare staff within the context of fear and uncertainty. New protocols were developed and disseminated, but staff were only able to enact required changes with the sustained example-setting, facilitation, compassion, and strategy of clinical leaders within their microsystems (i.e., front-line teams where care and patients meet).

Having strong leadership within close proximity to front-line staff who were attentive to successful change management strategies allowed actions and behaviors to be integrated into clinical leaders’ day-to-day work. In hindsight, the combination of thoughtful change strategy, quality improvement principles, and commitment to integrated care and whole-system quality created powerful physician leadership.

Our Context of Care Delivery

Kotter’s second step describes Building a Guiding Team of leaders, and our existing team of clinical leaders set the stage for success as the pandemic emerged. At our university-based health center in a rural community in upstate New York, our service population was approximately 24,000 students at a large research university. Primary care staff consisted of about 100 front-line staff members, including front desk, nursing, laboratory, pharmacy, radiology, physical therapy, nutrition, behavioral health, physician, and advanced practice professionals (APPs). The service model was an interprofessional, team-based, patient-centered medical home (PCMH), with three integrated units simultaneously operating on three floors within the health center. Each unit was managed jointly by three leaders: an Assistant Medical Director, supervising physicians and APPs; a Nurse Manager, supervising all nursing staff, including registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified medical assistants; and a Clinical Administrative Supervisor, supervising all front desk staff. Clinical leadership also was provided by supervisors of the affiliated services of laboratory, radiology, pharmacy, nutrition, physical therapy, and behavioral health services, for a total of 17 clinical leaders forming an operational leadership team, led by the Medical Director.

Before the pandemic, the Medical Director led the department using a vision grounded in improvement science, interprofessional teamwork, diversity, staff wellness, and whole-person primary care. Daily huddles were conducted on every integrated unit along with co-located affiliated services. Unit leadership met weekly to discuss the operational business of each microsystem, and a full clinical leadership team convened weekly to discuss broad topics that affected all services. All 100 staff members met monthly, and a weekly update email was distributed to share timely information for front-line staff. These structures and systems provided an important foundation for scaling up as the pandemic began.

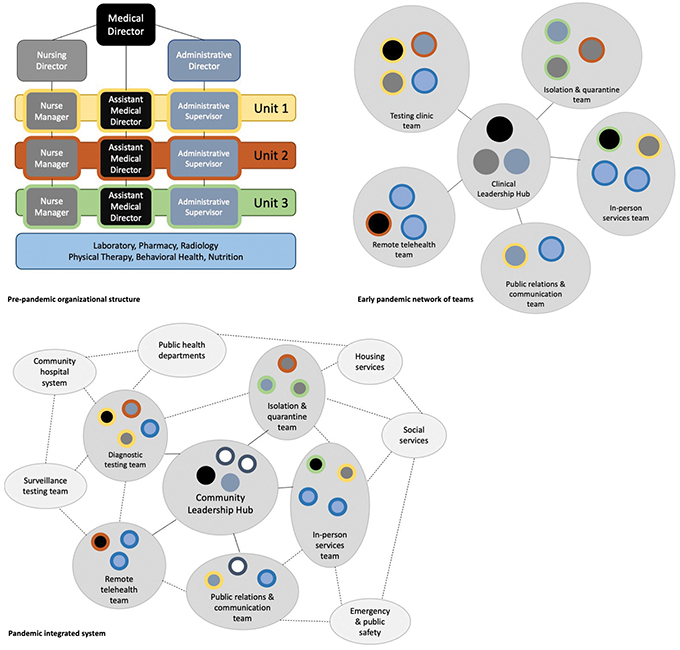

As the pandemic unfolded in early 2020, this effective matrix reporting structure transformed, by necessity, into a network of teams(7) (Figure 1). The normal work of full-service primary care was now inclusive of public health and pandemic-level requirements: testing, isolation and quarantine support, remote telehealth, in-person clinic, and public relations needs. Kotter’s third step, Building a Guiding Vision, felt natural to craft. We approached the impact of COVID-19 in our population by envisioning our new public health tasks as encompassed within the work of primary care, and believed our existing vision grounded in improvement, teamwork, diversity, wellness, and whole-person care would continue in this new healthcare landscape.

Figure 1. The evolution of a matrix reporting structure (top left panel), to a clinic-centric network of teams with a Clinical Leadership Hub (top right panel), to a community-focused, integrated collaboration with a Community Leadership Hub. Central and border shading in the top left panel are consistent throughout the panels, showing that the original units formed new teams, which became a unified and interconnected network. (Adapted from Alexander et al.(7))

Lessons Learned

Communicating with Consistency and Humanity

Kotter’s fourth step, Communicate for Buy-In, is as critical for crisis management as it is for change management. Public health guidance emphasizes the vital nature of steady, timely information during a crisis.(8) Each morning, a leadership huddle brought forward the pandemic news, institutional considerations, and updates from each professional group and local microsystem, including reports on how patients and staff were faring. The Medical Director shared key updates via email by noon each day. This steady internal communication kept pop-up questions to a minimum, because staff knew they could receive the latest updates at the same time, same way, each day. At times, a second daily update was sent if breaking news came in. Local clinical leaders were informed of the updates in order to answer questions and direct activities until the noon email was sent.

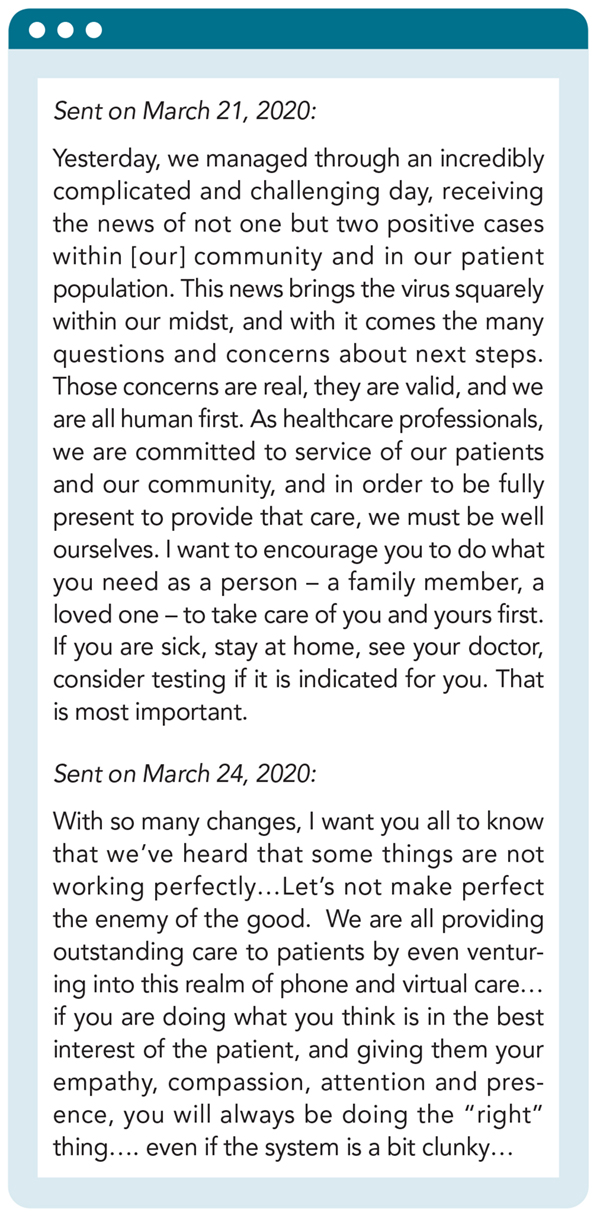

Communication in the early pandemic highlighted a conundrum: primary care staff represented a small group of essential workers required to be on-site, but PPE and social distancing prevented meaningful communication in person. Staff meetings were restricted to fewer than 10 people for 10 minutes. Thus, socially distanced huddles were the only in-person meetings allowed, but could not include all staff or teams. Virtual video and email became the only mechanisms to communicate with the entire department, necessitating a specific focus on writing meaningful messages and delivering thoughtful remarks through these platforms (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Early email notices acknowledging the human experience of being a healthcare professional during the pandemic, emphasizing the staff experience and encouraging connection despite the fragmentation all were experiencing.

Clinical leaders, who were already physically present in the clinical units, touched base with each other one-on-one or in small groups throughout the day, eventually letting go of the need for communication to come only from the Medical Director. In this way, our network of teams(7) now reached deeply across professional siloes, developing a close-knit, trusted group of unified clinical leaders who were empowered to act (Kotter’s fifth step). This network of integrated and interdependent teams created a constant feedback loop to assess and adjust communication style and strategy.

By winter of 2021, the network of clinical leaders became the primary drivers for staff communication, dropping the need for frequent mass email communication. Questions from front-line staff were collected and processed by the leadership team of each microsystem, improving timeliness and pace of communication. The close proximity of clinical leaders to front-line staff allowed for specificity of information. Messaging from the Medical Director became focused on communicating larger changes, conceptualizing the pandemic evolution for staff, and providing vision and direction at key timeline intervals.

Being the First to Try

The first telehealth visit, COVID-19 PCR swab, testing clinic, and medical rounds in isolation/quarantine units were all completed, in part, by clinical leaders. These actions led by example and demonstrated safety with the uncertain landscape of pandemic clinical care. Kotter’s sixth step is Creating Short-Term Wins, and each of these new experiences represented an overt achievement that generated excitement among staff. They also proved to cynics—along with those who were genuinely afraid to jump in—that it was possible for our clinic to implement and sustain pandemic changes. Studies have demonstrated the importance of clinical leaders being seen as experts in their field, committed to the foundational business of the operation,(9) and nothing gave our clinical leaders more credibility than being the first to try something new.

In late March of 2020, our primary care clinic was required to transition to a pandemic operations model, moving all appointments to telehealth and retaining in-person services for COVID-19 testing only.(10) On the first clinic day, anxiety was high among the core volunteer group performing nasopharyngeal swabs. Last-minute questions arose about proper swabbing technique, the possibility of mucous exposure if patients sneezed, and questioning which specific PPE was appropriate. Among the team of 15 testing clinic staffers on that first day, eight were clinical leaders. At that morning’s huddle, we led a Q&A session to address everyone’s fears about what could go wrong. This early in the pandemic, the virus’ level of contagiousness and possible airborne status was unknown, causing a focus on details surrounding technique and possible PPE breaches. By the end of that day, after testing over a dozen patients without any staff PPE breaches, the team was elated. There were cheers and high-fives to celebrate great teamwork that delivered necessary service to our community. Once this first clinic was done, many more staff followed suit, recognizing that they, too, could contribute safely to the testing effort. This same pattern continued for other necessary services throughout the pandemic. We Didn’t Let Up (Kotter’s seventh step): with each small win, led by clinical leaders, staff were reassured of the safety of the operation, and discovered how rewarding jumping in could be.

Focusing on these small wins—each as its own set of plan-do-study-act cycles—was pivotal in distributing the heavy workload among the full staff within the organization. This also helped to combat burnout when it inevitably set in.

Attending to Burnout and Moral Injury

The rapid pace of change could only be sustained for so long, until the rewards of small wins were out-balanced by burnout and moral-injury. Self-awareness, an essential resilience skill, simply wasn’t enough during pandemic response. Leaders needed to connect their self-awareness (what was happening in their inside world) with situational awareness (what was happening in the world around them). This process, termed integrative awareness,(11) has been shown to help leaders avoid overreacting to challenges, or jumping to conclusions, just to stop the discomfort of the weight of responsibility, and was vital to our team during the pandemic’s evolving stages.

We learned that for clinical leaders, this cognitive muscle was strong yet unrecognized. For example, the resolve it takes to lead a staff meeting, turning complaints into measurable aims and goals, requires integrative awareness. The attention required to place one’s hand on a doorknob and commit to being fully present with a patient, despite a mountain of administrative paperwork, is a practice in integrative awareness. This awareness is also present when we drive home, leaving fear and frustrations behind to enjoy time with family.

During the pandemic, these examples of mindfulness were heightened each day. Each staff meeting contained the usual frustrations of work demands, but now included valid fears of exposure, as staff questioned institutional support for front-line work. PPE supply, medicolegal liability, and lack of full understanding of the virus were common themes. Entering a patient room now required donning elaborate PPE, making it difficult to be fully present with the patient. The mental checklist prior to entry into an exam room and getting the encounter done quickly were now at the top of mind. Coming home, especially in the early stages of the pandemic, required comprehensive decontamination of physical stains, sweat, and usual healthcare stress, combined with valid new fears of transmission.

We found that when local clinical leadership designed the work environment to meet staff needs, basic frustrations were minimized.

Along with burnout, moral injury occurs when one engages in, fails to prevent, or witnesses acts that conflict with their values or beliefs.(12) For many front-line staff, urgent changes caused conflict with their ideals of quality healthcare. For example, many clinicians were uncomfortable providing care through telehealth without the ability to perform direct physical exams and without clear liability protection or technical support. Others wished to provide in-person care, but due to their own health, needed to work remotely. These tensions, along with unanswered questions about safety, cut to the core of being a healer, causing frustrations to build about minor clinical or operational details.

We found a few components essential to success in our setting. First, clinical leaders required the authority to create schedules that allowed for learning about changes and integrating them into workflow. In the face of uncertainty, front-line staff needed time to process. We found that when local clinical leadership designed the work environment to meet staff needs, basic frustrations were minimized. This allowed clinical leaders to focus on quick delivery of timely and necessary updates. Second, clinical leaders needed a safe space to strengthen their knowledge of outside situational events and process them through an emotional lens in order to strengthen integrative awareness. We created several touchpoints within meetings, huddles, and rounds, where clinical leaders and staff could unabashedly ask “Why?”, or “Can’t we do it this way?,” or express their own critical feedback on the pandemic situation or the institutional response. In order for us to Make Change Stick (Kotter’s eighth step), we needed to ensure that clinical leaders were addressing burnout and moral injury in themselves and among healthcare staff. Our change process created dependable systems, but the human impact to healers could not be underestimated. When continual improvement depends on the combined effort of all staff, each person needs to feel whole in order to implement sustainable changes.

Building Bridges to Strengthen Responses

Over time, it became clear that the work of the clinical enterprise was one important piece, but not the only component, of ensuring the health of our community. In order for the change to be truly sustainable (Kotter’s eighth step), we needed to expand our collaborations. Due to COVID-19’s propensity for asymptomatic spread, surveillance testing was an important early detection strategy, requiring partnerships with research, testing, and hospital systems. As surveillance testing increased, more disease was identified, and as cases increased, needs for isolation and quarantine ballooned, requiring collaborations with public health authorities. As isolation and quarantine numbers rose, proactively detecting spread of infection related to networks of interconnected patients was key to stopping the chain of transmission. Once at-risk communities were identified, public health education enhanced infection control, which was then carried out by a combination of public health, clinical staff, social services, and community leaders. In order to cover all of these component parts, we expanded the network of teams(7) (see Figure 1) from within the health center to multidisciplinary stakeholders across the institution, all connected by the pandemic response for our population. Clinical leaders in particular played major roles in this outreach process, working across professional disciplines to execute continual and smooth operational changes.

At this point in the pandemic response, the focus of clinical leaders shifted from internal and clinic-centric, to outward-facing and community-focused. The strong systems built within the clinic at the outset, now well-oiled, functioned smoothly with the strength of front-line staff. Clinical leaders within our health system built bridges within and across our institution. For example, leaders of triage and diagnostic testing interfaced with surveillance testing teams when these testing strategies were delineated. Leaders of isolation and quarantine worked directly with public health departments to apply standardized protocols for admission and discharge, and with housing experts to ensure that basic hygiene needs were met. Primary care staff dealing with the social and behavioral needs of patients were connected with mental health and social services. Primary care staff at the health center were deeply connected with emergency response and public safety officials.

These connections began with centralized committees serving as hubs, first with a Clinical Leadership Hub, which evolved into a Community Leadership Hub, which over time fostered interwoven connections between teams (see Figure 1). The communication dissemination that had evolved within the health center now expanded outward to collaborators across the institution. No longer were staff waiting for information to trickle down from institutional or organizational leadership, but, instead, clinical leaders from the health center interfaced directly with front-line leaders within public health, community institutions, educational organizations, and emergency and public safety.

Literature published prior to the pandemic demonstrated the importance of strong clinical services, the vital nature of public health infrastructure, and the significant impact of social and behavioral determinants of health.(13-15) Termed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement as whole system quality,(16,17) the pandemic highlighted the need for integrated systems: the process of attuning to the needs of the patients and customers, receiving feedback and input directly from front-line staff, and utilizing these critical voices to align the work of multidisciplinary teams of staff with the entire institution, including all services, funding inputs and outputs, and community connections.

Evidence now emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic elucidates the success of the combination of these factors(18)—not just the success of each system in separate siloes, but, rather, the power of integrated systems to function as a unit, reducing redundancy, improving efficiency, and optimizing quality for individual patients and populations. Our lived experience during this pandemic validates this evidence.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic created career-defining moments for leaders of every industry. Within healthcare settings, the pandemic created a microcosm of change management, reinforcing the essential nature of thoughtful strategy grounded in empathy to the human experience. These approaches must include the voices and perspectives of front-line staff, and clinical leaders are the vehicle through which these perspectives are heard and brought forward to the healthcare organization and the institution as a whole.

As the world braces for life post-pandemic, we offer these lessons to our future colleagues, emphasizing the importance of ensuring that true leadership reflects the voices and experiences of the front-line staff and the needs of the patients and community.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks Greg Ogrinc, MD, MS, for critical review of this manuscript. The author also expresses deep and sincere gratitude to the patients and front-line clinical teams at Cornell Health, along with the incredible cadre of clinical leaders who made the pandemic challenge a joyful transformation.

References

Dine CJ, Kahn JM, Abella BS, Asch DA, Shea JA. Key elements of clinical physician leadership at an academic medical center. Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(1):31-36. DOI: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00017.1.

Taylor CA, Taylor JC, Stoller JK. Exploring leadership competencies in established and aspiring physician leaders: an interview-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:748-754. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-008-0565-5.

Nieuwboer MS, van der Sande R, van der Marck MA, Olde Rikkert MGM, Perry M. Clinical leadership and integrated primary care: a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2019;25(1):7-18. DOI: 10.1080/13814788.2018.1515907.

Bisognano M, Kenney C. Leadership for the Triple Aim. Healthcare Executive. 2012;27(2):80-83.

D’Auria G, De Smet A. Leadership in a crisis: responding to the coronavirus outbreak and future challenges. McKinsey & Company. March 16, 2020. www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/leadership-in-a-crisis-responding-to-the-coronavirus-outbreak-and-future-challenges . Accessed December 2, 2021.

Kotter JP. Leading Change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1996.

Alexander A, De Smet A, Kleinman S, Mugayar-Baldocchi M. To weather a crisis, build a network of teams. McKinsey & Company. April 8, 2020. www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/to-weather-a-crisis-build-a-network-of-teams .

Howitt AM, Leonard HB. Against desperate peril: high performance in emergency preparation and response. In Gibbons DE, ed. Communicable Crises: Prevention, Response, and Recovery in the Global Arena. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing; 2007.

Gupta A. Physician versus non-physician CEOs: the effect of a leader’s professional background on the quality of hospital management and health care. J Hosp Adm. 2019;8(5):47-51. DOI: 10.5430/jha.v8n5p47.

Kelley S. Cornell Health ready to combat coronavirus. Cornell Chronicle. March 26, 2020. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2020/03/cornell-health-ready-combat-coronavirus .

Brassey J, Kruyt M. How to demonstrate calm and optimism in a crisis. McKinsey & Company. April 30, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/how-to-demonstrate-calm-and-optimism-in-a-crisis .

Ford EW. Stress, burnout and moral injury: the state of the healthcare workforce. J Healthc Manag. 2019;64:125-127. DOI: 10.1097/JHM-D-19-00058.

Cash-Gibson L. Technical series on primary health care: integrating health services. World Health Organization, 2018. www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health-care-conference/linkages.pdf . Accessed November 10, 2021.

Institute of Medicine. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. www.nap.edu/read/13381/chapter/1#ii . Accessed November 17, 2021.

Kinder K, Bazemore A, Taylor M, et al. Integrating primary care and public health to enhance response to a pandemic. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2021;Jun 10;22:e27. DOI: 10.1017/S1463423621000311.

Sampath B, Baldoza K, Lenoci-Edwards J, Barker P. An integrated approach to quality. Healthcare Executive. 2021;36(6):52-53.

McPherson M, Callender S, Lewis N. Working with community partners. Healthcare Executive. 2021;36(5):40-41.

Grenier A, Jabbarpour Y. Primary care and COVID-19: it’s complicated—leveraging primary care, public health, and social assets. Primary Care Collaborative. October 2021. www.pcpcc.org/resource/evidence2021 . Accessed November 10, 2021.