Despite greater investment in healthcare than any other nation, the United States remains an outlier for multiyear declines in health outcomes. Unique among the world’s wealthiest nations, the U.S. lacks universal coverage, has the lowest life expectancy, the highest rates of treatable condition-related deaths, and high maternal and infant mortality rates. Moreover, beyond the high obesity and comorbidity rates, Americans have fewer doctor visits and fewer hospital beds available compared to other countries.(1)

New perspectives and innovative ideas, especially from physicians who practice within the system, are needed to shape the health policy that drives change in healthcare. Unfortunately, the skillset needed to influence health policy change is lacking in most traditional clinician training programs.

Physicians’ perspectives have shifted to encompass a sense of duty in addressing health concerns, extending beyond clinical practice to include civic involvement and political engagement.(2) But the complexity of the U.S. healthcare system and recent rapid changes have created well-known challenges for modern physicians (and their patients).

Evolving technologies, the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift toward value-based care, cost-related policy changes, and demographic shifts have created a need to change the practice of medicine in this century and necessitated an expanded role for clinicians within public health and disease prevention. This requires knowledge of interprofessional management principles to improve healthcare delivery and outcomes,(3) and has placed an unofficial emphasis on leadership training(4) without the systematic compensation within physician training to meet the challenge.

To enhance the delivery of patient care on a systematic scale, physicians must acknowledge their unparalleled opportunity to shape the domains of health policy. Embracing this challenge with intentionality and commitment will empower them to make substantial and purposeful contributions to the future of healthcare.

This article outlines feasible steps to guide learners at any career stage who are interested in leading and contributing across health policy domains. The challenge lies in overcoming knowledge gaps and inspiring active engagement, leveraging physicians’ acquired wisdom to embark on transformative advancements in health policy disciplines.

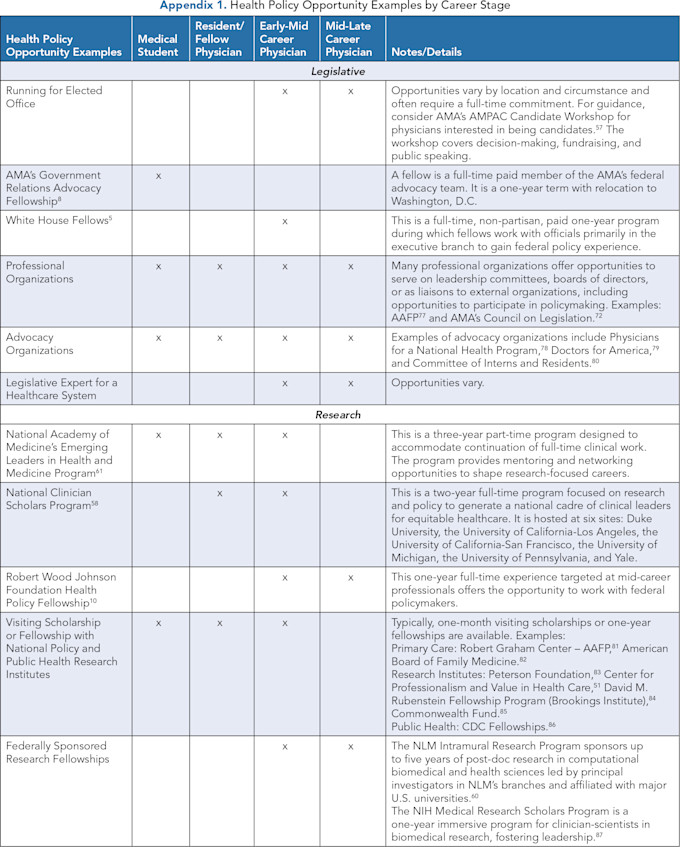

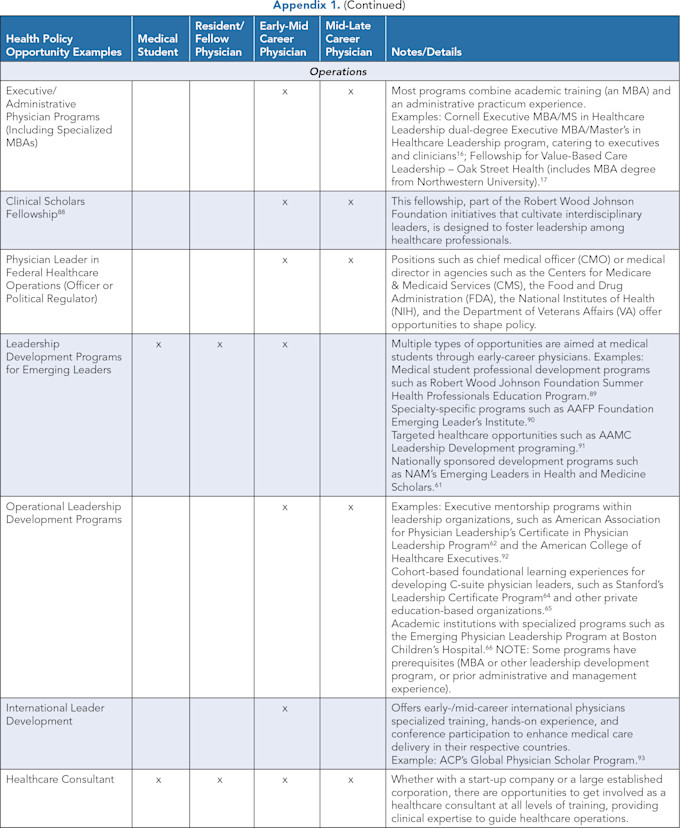

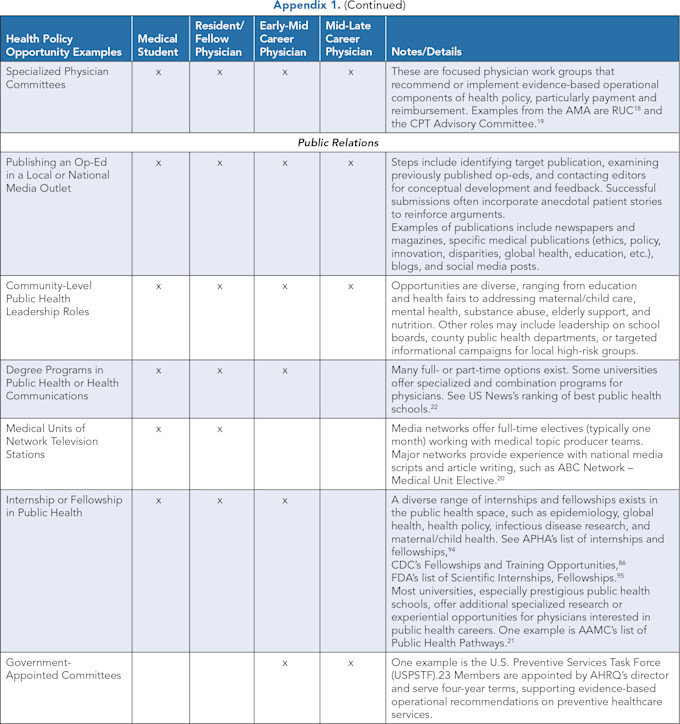

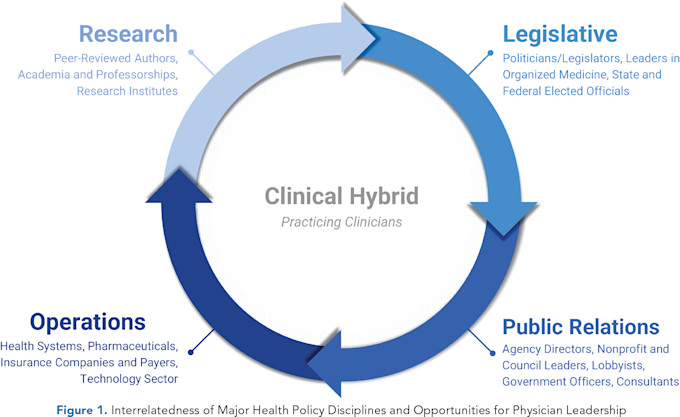

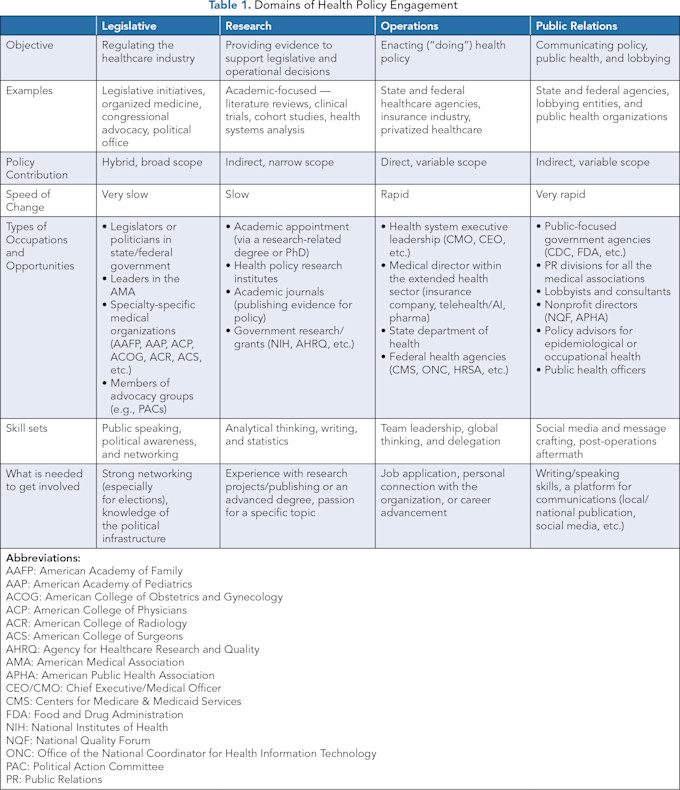

Within each health policy domain, distinct activities and approaches demand the cultivation of unique skill sets. Nonetheless, domains are interrelated in advancing the health policy landscape in general (Figure 1).

In the legislative domain, physicians navigate the intricacies of policymaking, engaging in politics-related efforts, usually within medical organizations or directly in the government. In the research domain, physicians delve into evidence-based studies and academic contributions that indirectly shape legislative decisions. In operations, guided by policy, physicians lead the implementation of efficiency and quality in healthcare delivery. And in public relations, experts shape healthcare communication strategies to influence the culture of medical practice and public health.

While these domains collaborate to drive positive change in healthcare collectively, their distinct functions underscore the spectrum of skills needed to influence health policy at large (Table 1).

THE LEGISLATIVE DOMAIN

Physicians play a key role in connecting policies with medical practice (Figure 1). Through active involvement in policymaking, doctors can guide medical research toward achieving positive results within the context of patient care.(1)

Physicians engaging in legislative health policy efforts typically focus on two pathways: directly within the government(5,6) or indirectly via medical organizations.(7,8) Both pathways can provide robust and fulfilling careers and require nuanced skillset differences. Regardless of the path, physicians focusing on the legislative domain of health policy will need strong communication skills and professional networks fueled by a passion for political awareness.

In the learner stage, physicians explore policymaking through roles in professional societies, advocacy groups, or government internships. Activities such as serving as voting delegates or engaging in congressional advocacy build foundational knowledge, guided by mentorship.

As contributors, physicians take on leadership roles in advocacy committees, fellowships, or government agencies, gaining hands-on legislative experience. Opportunities like candidate workshops and elected positions within organizations prepare them for more significant policy impact.

In the leader stage, physicians hold high-impact roles, such as legislative committee chairs, organizational board members, or government health officials. These positions enable them to guide policy reform, advocate for patients, and shape public health at scale.

Across these stages, the legislative domain offers physicians a platform to address pressing healthcare challenges where their expertise informs decisions that affect the broader healthcare landscape. Leaders in this arena have the potential to shape highly influential aspects of health policy that can have lasting, large-scale effects.(9)

THE RESEARCH DOMAIN

The career trajectory in research and academia allows physicians to shape the future of healthcare as thought leaders. Their insight provides innovative and authoritative groundwork for solutions to problems. The goal of the research trajectory is to ask the important questions. This sometimes requires taking a step back from the daily routine to focus on what could be rather than what is.

As learners, they seek foundational experiences, often confronting the challenge of bridging knowledge gaps in research culture. This builds research knowledge that involves mentorship, self-paced study, and participation in foundational activities — for example, understanding research methods, co-authoring publications, and engaging in hands-on experiences as visiting scholars to develop practical skills for academic growth.

As contributors, physicians might take on advanced roles in research by pursuing academic programs (e.g., MPH) or fellowships to deepen their expertise.(10,11) These programs provide immersive experiences and access to collaborations with experts, securing resources, and independently publishing in their areas of interest. Advanced clinical research(12) or faculty development(13) training are other examples of this leadership development in academia.

Finally, as leaders, academic physicians use their expertise to influence change across health policy domains, from substantiating legislative arguments and operational efforts to shaping public relations content. Influential roles could include directing policy research institutes or serving in hybrid academic and operational positions to inform legislative policies, enhance healthcare operations, and support public health communications.

THE OPERATIONS DOMAIN

Operational leadership in healthcare offers diverse and impactful opportunities for physicians that directly improve patient outcomes and organizational efficiency.

Learners are typically early-career, focused on gaining foundational knowledge and real-world exposure to healthcare operations, such as value-based care, health IT, and healthcare policy implementation. Examples include internships or project-based opportunities in healthcare institutions, which allow them to observe the intersection of policy and practice. Proactive networking and self-marketing can create unique opportunities, such as internships with state or federal agencies or electives in public health operations.(14,15)

As contributors, mid-career physicians often blend formal education with practical leadership roles. Opportunities like accelerated MBA programs paired with administrative practicums, leadership fellowships, or hybrid dual-degree programs (e.g., MBA/MS) allow contributors to participate in executive mentorship and cohort-based leadership training.(16,17) The result is applied operations — understanding the medicine, research, and policy while furnishing the professional skills needed to lead interdisciplinary teams in enterprise-wide initiatives.

In the leader stage, late-career physicians take on high-impact roles, such as chief medical officers or senior-level positions in government agencies like CMS or NIH. Leaders drive systemic change through strategic decision-making, guiding healthcare policy, and operationalizing evidence-based initiatives. They may also lead specialized workgroups, such as those addressing reimbursement or procedural standards, or act as consultants within industry or government sectors.(18,19)

THE PUBLIC RELATIONS DOMAIN

Physicians in public relations serve as authoritative communicators of health information. Engaging with both professional and public audiences, their contributions span political, academic, and operational spheres, addressing diverse health policy topics and influencing healthcare awareness through roles ranging from local advocacy to national media leadership.

Roles in public relations vary based on a physician’s stage in their health policy journey, and encompass a broad range, from consulting and lobbying to government agency leadership to a public spokesperson in media outlets.

As learners, physicians explore public-facing communication through mentorship and practical experiences. Writing op-eds, participating in community health fairs, and giving talks at local events provide foundational exposure. Learners may also access electives or visiting scholar programs focused on public health communications, enabling them to explore topics like epidemiology, health policy, or infectious disease research while building communication skills.

As contributors, physicians refine their communicative expertise, perhaps by pursuing internships or fellowships at institutions like the CDC or FDA. Opportunities include contributing to national media, leading awareness campaigns, and engaging with targeted public health initiatives.(20,21) Advanced public health degrees can further prepare contributors for leadership in specialized areas such as global health or policy advocacy.(22)

As leaders, physicians are prominent public health spokespersons, such as government advisors or members of influential organizations like the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.(23) For example, Anthony Fauci became the face of the federal response to the COVID-19 pandemic.(24) His specific experience equipped him to make urgent, large-scale decisions and withstand the political blowback exacerbated by rampant misinformation.(2) Leaders in public relations mentor emerging contributors and shape public health communication strategies, using their expertise to drive systemic healthcare improvements and influence policy on a national and global scale. Their evolving influence on health policy and public awareness is instrumental in shaping the healthcare landscape over time.

SUMMARIZING THE DOMAINS OF HEALTH POLICY

The vital contributions of physicians in advancing equity, enhancing clinical treatment, and promoting cost-effectiveness are essential in promoting sustainable improvements to patient outcomes. Despite limited health policy training in their graduate medical education, physicians can overcome knowledge gaps to influence policy reform meaningfully. Across the domains of health policy — legislative, research, operations, and public relations — there are diverse avenues for engagement, each requiring distinct skill sets and providing opportunities for physicians to shape the future of healthcare (see Appendix 1).

Despite the challenges of a fragmented U.S. healthcare system, physicians actively engaging in legislative initiatives, research, healthcare operations, and health policy communication can drive meaningful change in patient care and public health. These pathways provide a roadmap for physicians at any career stage to progress from learners to leaders, highlighting the importance of structured training, professional networking, and intentional involvement.

By bridging the gap between policy and practice, physicians can leverage their leadership to drive the innovation that can guide the most pressing challenges of our time: steering our healthcare system toward equity, efficiency, and sustainability.

LEARNING HEALTH POLICY

Physicians are uniquely poised to influence innovation in health policy reform, but research suggests medical education provides insufficient training in health policy.(25) Moreover, the physician’s role has expanded to include disease prevention and leadership training without the concomitant expansion of such education in medical training. Graduating physicians report feeling ill-equipped to apply health policy knowledge in practical settings, highlighting a gap between healthcare practitioners and their ability to make change.

It is well-known that physicians at various training stages are interested in learning about and contributing to health policy efforts nationally(26) and internationally.(27) Consistent evidence supports exposing medical trainees to health policy education to increase their interest in and knowledge of health policy.(28)

Surveys of U.S. medical school deans reveal that medical education provides insufficient training in health policy.(25) Additionally, data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reveal that graduating physicians are historically underprepared regarding health policy training.(29) Moreover, although the ACGME has specific milestones for exposing trainees to aspects of health policy(30) — alluding to the importance of this knowledge in GME — graduating physicians may not be equipped to apply this knowledge in a practical way sufficiently. This has prompted the targeting of educational initiatives, particularly in emphasizing health systems science as the “third pillar” of medical education.(31,32)

The difficulty in addressing health policy within medical education is the breadth of health policy scope and the evolving nature of health systems science. Complicated by the multi-payer structure of U.S. healthcare and culturally embedded regional teaching practices, there is variability in health policy education.(33)

Traditionally, the approach to integrating health policy curriculum into medical education has been brief at best. Generally, physicians have only limited exposure to influential health policy concepts like healthcare finance (such as payers, insurance types, quality, and managed care, etc.), health law (such as patient privacy, malpractice, coverage and access, or controlled substance regulation, etc.), policy-related career options (such as elected/appointed positions, public and private healthcare leadership, academia and research institutes, etc.), writing/researching legislation or resolutions, and physician roles within governmental agencies.(34,35)

Thus, without foundational knowledge, it’s not surprising that only a small fraction of physicians play an active role in shaping the field.(36) This alludes to a relationship between knowledge and engagement in health policy efforts.

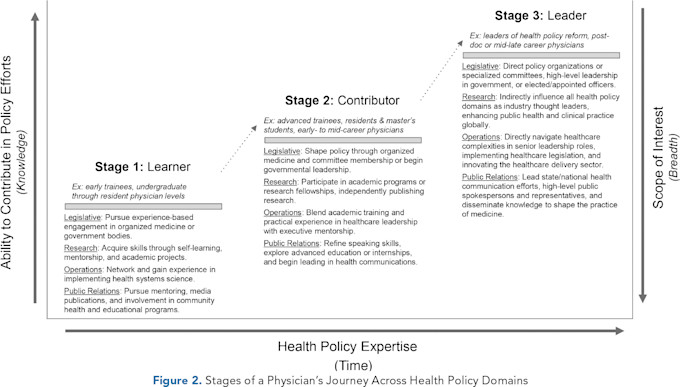

An influential career as a physician in health policy involves a progression from “learner” to mid-career “contributor” to “leader” (Figure 2). At the learner stage, interest in health policy is broad and under-defined, and a feeling of overwhelm can emerge at the options or involvement. For example, a learner might lack practical experience in conducting academic investigations or institutional knowledge to make a difference within their workplace, local government, or professional advocacy organizations.

Ultimately, targeted health policy education should help physician trainees identify opportunities for contribution. Seeking out these experiences is the first and rate-limiting step for learners, but it is what allows physicians to develop the expertise that leads to contribution potential.(37,38) The learner stage defines an education-focused phase (typically medical students, residents, and young physicians) where there is limited expertise in health policy domains, hampering the ability to contribute to the field.

Targeted education on health policy shapes professional roles to help physician trainees identify opportunities for contributing. Qualitative research consistently supports the high interest of trainees in advocating for health policy change and the desire for more opportunities to learn about and participate in policy discussions during their training.(39) In addition, immersive experiences that integrate the effect of health policy on the population being clinically served have demonstrated a beneficial effect on physicians’ health policy knowledge.(28,40)

Medical students may not realize that such opportunities can be used as official electives to supplement training and the pursuit of individual academic interests — including contributory efforts in health policy. “Structural competence, cultural competence, and health inequities” are standardized components of curricular content at medical schools,(41) allowing trainees to explore curricular and extracurricular health policy opportunities.

The Legislative Domain

One effective avenue for nurturing legislative interests during the early stages of a medical career is through engagement with professional medical societies, associations, and special interest groups. These organizations are typically well-structured, adequately funded, and have the capacity to effect tangible change.(42) Most medical organizations designate specific leadership positions for medical students and residents who can participate in policy development, lobbying efforts, and advocacy campaigns. Roles for learners range from delegates in policymaking bodies(7) to members of the board of directors.(43)

Additionally, medical organizations typically host a range of commissions or committees that facilitate the engagement of young trainees or early-career physicians.(44) These opportunities offer a rich networking environment, positioning learners at the decision-making table alongside experienced professionals. State and national chapters of medical organizations and specialty societies provide ample opportunity for learners to cultivate their expertise.(45)

Learners can also explore more direct, government-facing opportunities, including participating in various medical advocacy groups, engaging directly in congressional advocacy opportunities at the state or national level,(46) volunteering in political campaigns or grassroots efforts,(47) and interning in congressional offices.(48) Medical students and residents can use elective time for engagement in such legislative-related activities.

The primary objective at the learner stage is to gain exposure to the breadth of involvement in the legislative process, allowing individuals to refine their areas of interest. Mentors are immensely valuable during this phase, particularly in helping learners develop a professional network aligned with their specific interests.

The Research Domain

Entering the policy research space as a learner can be daunting. Without a strong mentor or an advanced degree like an MPH, students may struggle to overcome the significant knowledge gap, necessitating proactive self-paced learning and immersion in the research culture. A critical component of this process is seeking mentors who can provide guidance in refining research interests and navigating the academic landscape.(49,50) Self-paced learning becomes essential for acquiring foundational research knowledge, including research methodologies and data analysis.

Actively participating in research activities early in a physician’s career promotes exposure to the research process, from designing studies to publishing. Honing public speaking skills is an often-overlooked key to success for learners pursuing leadership in health policy research. Also, learners may benefit from the experience of presenting research.

At this stage, learners often have the opportunity to earn recognition in a publication’s acknowledgment section or be included in the list of authors for their substantial contributions. Visiting scholar opportunities are available to learners, providing hands-on experience. This stage is reminiscent of apprenticeship — learners are focused on acquiring tools and skills from experienced researchers, including grant writing, ethical research conduct, and effective scientific communication. It’s a journey of continuous learning and growth within the research community.

The Operations Domain

In the early stages of their medical career, learners might benefit from exposure to foundational concepts and hands-on experiences in healthcare operations, bridging their gap in knowledge of the health system. Specialized coursework or self-directed learning can provide this exposure.

While various resources offer insights into health policy, hands-on practical experience is crucial for developing expertise, scope, and professional networking. Effective learners gain exposure to seeing the application of legislation and research at healthcare institutions in real time. While specialized electives or internships can provide an overview of healthcare operations in executive or legislative settings, many learners can market themselves successfully to generate unique opportunities by leveraging their physician or trainee status.(51)

Self-marketing is a valuable skill for learners aspiring to executive or director roles in healthcare. For example, learners interested in leadership roles such as a chief medical officer or chief executive officer can begin with informational interviews and develop these relationships into a formalized internship or elective, even as a medical student or resident. Local, state, or federal health agencies, such as those within the Department of Health and Human Services, can offer similar opportunities.(14) Specific disciplines also offer elective opportunities for trainees, such as experience within public health operations.(15)

Engaging in project-based internships allows learners to actively participate in healthcare operations initiatives, covering topics like multi-payer systems, value-based care, implementation science, health IT, and state and federal policy. Transitioning from the learner stage can also be accelerated by pursuing formalized training, such as advanced degrees, or by transitioning between jobs. To take full advantage of these opportunities when they arise, learners should maintain an updated CV and resume.

The Public Relations Domain

Learners exploring public relations can take several key steps. In addition to gaining mentorship,(52) physicians can begin writing professionally by identifying target publications and examining previously published op-eds to gain insights into effective communication strategies. Seeking feedback from mentors, specialists, and editors is essential for developing expertise and written communication skills.

Learners should also consider alternative, community-specific opportunities, such as contributing to the county health department literature or local news publications(53) and participating in health fairs, vaccination drives, and task forces focused on addressing opioids or other community needs. They should also consider community speaking engagements, for instance, at local high schools or town halls.

The learner stage is unique in offering opportunities to engage in educational initiatives. Many hands-on experiences are tailored for medical students, residents, and early-career physicians who can explore part-time options. Further, there are a variety of specialized programs for physicians and trainees interested in public relations and healthcare communication.(20) Learners can apply for visiting scholar opportunities or electives at public health institutions.

Many medical schools and residency programs offer specific elective opportunities in public relations, allowing trainees to qualify for LCME- or ACGME-approved credit.(54) These experiences allow physicians to delve deeper into research and practical applications within public health, exploring topics such as epidemiology, health policy, and infectious disease research that can provide valuable exposure to public health and communications.(55)

Summary of the Learner’s Journey

Current gaps in knowledge in health policy among physicians highlight their need to learn about health systems science, legislative processes, and healthcare operations. Regardless of their career stage, physicians must strive to enhance their knowledge by actively seeking learning opportunities and contributing to health policy, facilitating their emergence as indispensable leaders.

As physicians take charge of shaping health policy disciplines, they go beyond intentionality to make transformative steps toward shaping the future of healthcare. Ultimately, improving patient care on a systemic scale requires physicians to recognize their unique potential in shaping health policy domains — a potential borne from a willingness to step up to the challenge.

CONTRIBUTING TO HEALTH POLICY

Physicians’ perspectives have shifted to extend beyond clinical practice to include civic involvement and political engagement.(2) However, the complexity of the U.S. healthcare system and recent rapid changes have created recognized challenges for modern physicians (and their patients).

Evolving technologies, the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift toward value-based care, cost-related policy changes, and demographic shifts have created a need to change the practice of medicine in this century and necessitated an expanded role for clinicians within public health and disease prevention. This requires knowledge of interprofessional management principles to improve healthcare delivery and outcomes(3) and has placed an unofficial emphasis on leadership training without the systematic compensation within physician training to meet the challenge. The multifaceted journey of physicians navigating the domains of health policy offers a spectrum of experiences. This transformative journey unfolds across three distinct stages: “learners,” “contributors,” and “leaders” (Figure 2).

The second stage of the journey is as a health policy contributor, defined by the ability to meaningfully contribute expert knowledge from acquired experience as a learner. Physicians at this stage have generally realized their interest in contributing to health policy efforts and have taken steps toward developing their expertise. These are typically physician trainees or young physicians with prior exposure to health policy or mid-career physicians who realize additional concentrated training is needed to bolster their knowledge for career advancement.

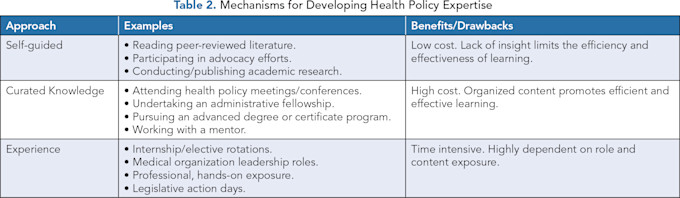

Acquisition of expertise is generally via three approaches: self-guidance, curated knowledge, or personal experience (Table 2). Each of these approaches has benefits and drawbacks with respect to cost, time investment, and experiential outcomes. However, physician engagement in health policy early on in one’s professional journey appears to offer significant advantages. This involvement provides valuable insight into the constantly evolving policy landscape, which can guide pertinent research and lead to a larger, meaningful influence on healthcare.(56)

The Legislative Domain

Similar to a learner’s journey, contributors choose between direct or indirect legislative roles within governmental bodies or medical organizations. Within organized medicine, they may explore opportunities in government relations or participate in specific fellowships designed to nurture these skills.(8) Active participation in professional organizations, involvement in commissions or committees, and leadership roles in medical interest groups are all meaningful avenues for physicians to shape healthcare policy collaboratively.(7)

Contributors might pursue more direct engagement with the government through programs that place them in high-level positions within state or federal agencies.(5) Several organizations offer fellowships in Washington, D.C., that allow individuals to gain invaluable federal policy experience.(6) These paid, nonpartisan opportunities for developing leaders are available across the branches of the federal government.

Emerging from these unique experiences that expose them to their particular areas of interest, contributors become equipped to pursue leadership options, such as elected positions within organized medicine or in political offices at the state or federal levels. These roles often demand a full-time commitment and can be complemented by participation in candidate workshops,(57) which can furnish physicians with essential political skills.

The Research Domain

Transitioning from a learner to a contributor in health policy research entails gaining the practical experience needed to gradually assume more substantial research roles, all while building a network of mentors and collaborators. As physicians advance to the contributor stage, they can amplify their impact on the research landscape by participating in a range of academic programs that provide funding, abundant resources, and the opportunity to collaborate with international experts.(58) Many master’s-level academic programs offer a two-year, full-time focus on research and policy to develop clinical leaders for equitable healthcare impact.

Alternatively, contributors interested in health policy research can pursue a research fellowship. These are typically one-year immersive experiences working with policy research institutions.(10,59) There are also numerous full-time and part-time sponsored public health research fellowships available for physicians interested in making research a quintessential aspect of their careers.(60,61) Experience can also be obtained independently with strong professional networks and sufficient resources to publish prolifically in an area of interest.

Tenacious physicians can augment their efforts with resources such as access to data, statisticians, and funding. Participating in research activities not only cultivates the expertise needed, but also empowers contributors to make meaningful and substantial contributions to academic literature. This process lays the foundation for their journey toward becoming influential thought leaders in healthcare.

The Operations Domain

Early-career physicians may engage in opportunities that augment their roles in healthcare operations by blending formal academic training with practical administrative experience. These avenues for growth encompass a spectrum of learning methods, including advanced education, typically specialized MBA programs coupled with an administrative practicum or internships, fellowships, and leadership positions within operational settings.

Hybrid options also exist. For example, contributors can explore administrative fellowships in value-based care where an MBA degree is included in the training.(17) Similarly, some executive programs in healthcare leadership offer dual-degree programs (e.g., (MBA/MS) tailored to executives and clinicians, ensuring seamless career progression.(16)

Other academic programs offer similar experiences that provide access to large, influential professional networks. These flagship examples offer a robust training environment that equips contributors with a sturdy foundation to emerge as interdisciplinary leaders.

Mid-career physicians looking to bolster their health operations leadership potential can explore opportunities in executive mentorship programs, specialized programs in academic institutions, or in industry (electronic medical records, insurance, administration, etc.). For example, several esteemed leadership organizations, such as the American Association for Physician Leadership(62) and the American College of Healthcare Executives,(63) have specialized training and rich professional networks. Contributors can immerse themselves in cohort-based foundational learning experiences within university-affiliated leadership certificate programs(64) and analogous programs offered by private educational leadership institutions.(65) Several prestigious academic institutions extend specialized emerging leadership programs with varying prerequisites in administrative and management experience.(66)

Regardless of the path chosen, targeted leadership training and practical experience empower contributors with expertise that spans across health policy domains, enhancing their potential for healthcare operations leadership.

The Public Relations Domain

Typically in their early-career period, contributors may build on foundational experiences in public relations by refining writing/speaking skills, exploring advanced education options, or completing specialized internships and fellowships. Opportunities at accredited institutions or government agencies provide valuable exposure to healthcare communication strategies. Contributors in this field expand their horizons by venturing into roles involving national media, scriptwriting, or article authorship. As they accumulate expertise, they might assume leadership roles within county health departments and organization boards or lead targeted awareness campaigns.

Those who pursue advanced degree programs in public health or health communications (e.g., MPH or MPP) have specific but flexible options, including specialized programs at prestigious universities.(22) This can equip contributors with the necessary experience for rapid progression into public relations leadership roles.

There is consistent evidence that physicians with advanced degrees (e.g., MBA) tend to have a competitive edge and more opportunities for career advancement. Regardless of their ability to influence health policy directly, these physicians tend to have a better understanding of public health issues.(67) Additionally, joining influential groups or government organizations can empower contributors to shape healthcare communication on a broader scale early on.

The end of the contributor stage is marked by expertise in a focused area of public relations, such as epidemiology, global health, health policy, or infectious disease, with possible prospects of leading within organizations like the CDC, FDA, and APHA.

For physician trainees, elective time can be used to self-guide health policy exposure or procure specialized health policy training in specific domains, such as administrative or research opportunities. Additionally, many professional and physician advocacy organizations offer leadership development opportunities for learners that can expose them to a sampling of opportunities going forward. As noted above, these types of opportunities are substantiated by national accrediting bodies.

For residents, according to section I.B.3.a of the ACGME common program requirements, those interested in health policy experiences can undertake unique elective opportunities at locations non-affiliated with the main training institution.(68) These guidelines specify the quality of education, ensured with a standardized program letter of agreement (PLAs), including identifying responsible faculty, specifying teaching and evaluation roles, determining experience details, and outlining education policies.

Trainees have taken advantage of these opportunities during elective time to intern at large government departments and federal organizations, such as state health departments, congressional offices, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.(69)

Summary of the Contributor’s Journey

As contributors, physicians bridge the gap between learning and leadership by applying their growing expertise across the domains of health policy. This stage is marked by a progression from foundational exposure to focused, impactful contributions that set the groundwork for leadership in health policy.

By investing in structured opportunities (e.g., fellowships, leadership roles, advanced academic programs, etc.), contributors gain practical experience and refine their expertise. The opportunity to lead initiatives in a contributor role is pivotal for the growing leader, as mentorship and oversight can fine-tune the contributor’s scope of interest while making a meaningful impact on patient outcomes.

LEADERSHIP IN HEALTH POLICY

Physicians at the “leader” stage of their health policy journey hold pivotal roles in influencing healthcare at the highest levels. With expertise developed through deep learning and contributor experience (Figure 2), leaders integrate clinical knowledge, research acumen, and operational insight to shape policy and public health initiatives. Physician leaders apply a spectrum of domain-specific skills to guide systemic changes, improve care delivery, and advocate for evidence-based practices. These roles are distinguished by their ability to affect large-scale healthcare transformation, positioning such leaders at the forefront of shaping the healthcare landscape.(70)

Becoming a leader in health policy is not a straightforward or guaranteed process, nor is there necessarily a linear progression from learner to leader. The process is often organic and relies on a continuous cycle of learning, augmented by a professional network of other experts and leaders to bolster efforts for change. Moreover, there are hierarchies within leadership that require time and experience to navigate. The majority of health policy leaders are non-physicians, and they are often as (or more) effective change agents than physician leaders.

The demands of clinical medicine are nearly total, and the central decision a physician interested in leading policy change needs to answer is whether the potential impact of their policy efforts can outweigh the lost time caring for patients. For physicians and others in caring professions, these are difficult choices to make.

The qualities that make an effective physician leader in any field of medicine are also those that distinguish physician leaders in health policy. Clinical training experiences leave physicians with a rich operational and executive skillset that translates well to policy leadership. Depending on the opportunity landscape, personal and geographic priorities, and work preferences, physician leaders may find themselves most suited to policymaking, directly involving themselves in politics, focusing on policy-engaged research as an academic, or leading operationally focused teams.

Any physician outside of clinical medicine operates with knowledge as a “hybrid” of clinician-investigator, clinician-policymaker, or clinician-politician (Figure 1). This reflects the knowledge, skills, and mindsets developed over the 7–10 years of clinical training — physician leaders in health policy are first and foremost, physicians. Through continuous learning, these physicians often lead from academic, operational, or hybrid roles as they influence health policy from multiple angles.(71)

The Legislative Domain

Physicians in the leader stage attain influential roles within policymaking bodies of professional medical organizations or the government. These roles demand a deep understanding of parliamentary procedures and allow physicians to guide policymaking in their fields of interest.

Leaders within professional medical organizations may find themselves directing legislative-focused physician committees,(72) occupying positions on the boards of directors, or representing their medical specialties as section delegates.(73) These leaders can also serve as effective lobbyists, often appearing in congressional hearings as clinical and patient advocates.

It is important, however, that physicians pursuing this path be aware of the hazards of becoming the public face of policy agenda. For example, Anthony Fauci received significant public criticism in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic for his federal public health efforts.

Physicians can also channel their focus toward political roles within government. Political involvement beyond financial contributions or volunteering distinguishes leaders from contributors as they direct influential organizations and public offices.(9)

Leader roles encompass elected positions across the government, including state assemblies or the federal Congress. Other elected or appointed positions combine operational and public relations aspects, such as a health secretary, public health officer, or agency director. A physician’s clinical insight into these roles equips legislative leaders with a depth of knowledge, augmenting their capacity to shape healthcare policy and public health initiatives.(74)

The Research Domain

For physicians interested in full-time clinician-researcher roles,(75) diverse opportunities are accessible, often through connections with academic institutions or research institutes. Leaders who have honed their research-based skillset can spearhead efforts that influence the other domains of health policy. For example, published research can influence legislative (political) or operational efforts and bolster the credibility of public health announcements. These leaders might run a policy research institute, impart their knowledge at premier academic institutions through influential publications, or assume a hybrid operational and academic role, such as a senior-level position at the National Institutes of Health.

Research leaders are successful in securing substantial funding opportunities, which can be used to illuminate large problems in healthcare and test innovative solutions. These leaders also have the potential to make a significant impact on healthcare by utilizing the evidence they publish to influence the practice of medicine on a global scale.

Physician leaders have an intimate understanding of the challenges and opportunities within the healthcare system. This insight equips them to make informed decisions that benefit patients and providers on a large operational scale. These leaders have expert knowledge and skill, enabling them to spearhead projects and system-level changes that profoundly impact the healthcare sector. Diverse positions range from serving as organizational board directors, high-ranking government officials, and think tank managers to healthcare executives.

The Operations Domain

Leaders in healthcare operations are typically in the mid to late stages of their careers. They are positioned to heavily influence healthcare policy, improve care delivery, and drive public health initiatives. Roles like chief medical officer (CMO) or medical director in federal agencies such as CMS, FDA, NIH, and VA offer substantial platforms to shape healthcare policy on a national level.

Physicians at this stage can also contribute to focused physician workgroups that recommend and implement evidence-based operational components of health policy, particularly related to payment and reimbursement. These are often seats of significant influence and may require leaders to be cognizant of the power they wield.(76)

The American Medical Association offers examples of such workgroups, such as the RVS (Resource-Based Relative Value Scale) Update Committee (RUC)(18) and the Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) Advisory Committee.(19) Additionally, consultants serve as crucial leaders in healthcare operations decisions, whether within a start-up company, a large corporation, or in the federal government.

The Public Relations Domain

For mid-to-late career physicians, the journey may culminate in a role as a public relations leader, focused on pioneering health communications efforts. These physicians have extensive experience and can make valuable contributions to a diverse range of communication outlets.

Leaders expand their capacity by mentoring and guiding learners and contributors as they embark on or develop specialized areas of public relations. Vocationally, leaders in public relations might explore high-level leadership roles within prestigious institutions or governmental agencies or as appointed officials/spokespersons.

They may also consider membership in influential organizations such as the National Quality Forum or the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, where their expertise can contribute to evidence-based improvements in healthcare delivery.(23) The hallmark of leaders in this domain is continuing to advance the field of public relations, disseminating their wealth of knowledge to shape healthcare changes on multiple fronts.

Summary of the Leader’s Journey

The leader stage of a physician’s journey in health policy is marked by the ability to enact change at the institutional, national, and global levels. Physician leaders significantly influence legislative agendas, advance research-based solutions, spearhead innovative healthcare operations, and shape public health efforts. Their efforts address the complexities of modern healthcare and inspire future generations of physicians to engage in health policy.

Physicians leading in health policy continually hone and refine skillsets within their respective areas of interest and expertise. The interconnectedness of domains illustrates the diverse landscape of a physician’s journey in health policy and the spectrum of involvement at various career stages. Ultimately, there is a call for physicians to step up to the challenge of shaping the healthcare industry by leading across the domains of health policy for patients now and in the future.

References

Munira G, Reginald W. U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes. Issue Brief. The Commonwealth Fund. January 31, 2023. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022 .

Gruen RL, Campbell EG, Blumenthal D. Public Roles of US Physicians: Community Participation, Political Involvement, and Collective Advocacy. JAMA. 2006;296(20):2467–2475. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.20.2467

Bai H. Modernizing Medical Education through Leadership Development. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93(3):433–439. PMID PMC7448395.

Yau AA, Cortez P, Auguste BL. The Physician Leader: Teaching Leadership in Medicine. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2022;29(6):539–545. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2022.08.002

White House Fellows. The White House. https://whff.org/the-program/ .

U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Presidential Management Fellows Program. Accessed August 21, 2023. http://www.pmf.gov/ .

American Medical Association. Medical Student Leadership Opportunities. Updated June 30, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/medical-students/medical-school-life/medical-student-leadership-opportunities .

American Medical Association. Government Relations Advocacy Fellow (GRAF). https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/government-relations-advocacy-fellow-graf

Alvarado R. Physicians Role in Politics. Kentucky Doc. 2017 (Winter): 20–21. https://www.lexingtondoctors.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Physicians-Role-in-Politics-by-Ralph-Alvarado-MD.pdf .

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Fellows. Lifetime Achievement Award. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://healthpolicyfellRoberows.org/alumni/awards/ .

National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. Medical Research Scholars Program. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cc.nih.gov/training/mrsp .

Liao S, Lavender C, Zhai H, Zhou X. Predictors of Academic Career Progression Among Early Career Physician-Scientists via an Intensive Research Training Program Abroad: A Case Study. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04069-8

Steinert Y, Naismith L, Mann K. Faculty Development Initiatives Designed to Promote Leadership in Medical Education. A BEME Systematic Review: BEME Guide No. 19. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):483–503. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2012.680937

ABMS Visiting Scholars Program. Shaping the Next Generation of Research Leaders in Health Care. American Board of Medical Specialties. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.abms.org/early-career-research-grants/ .

NYC Health. Elective in Public Health for Medical Students and Residents. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.nyc.gov/site/doh/about/employment/residency-program-fellowship-elective.page

Cornell. Cornell Executive MBA/MS in Healthcare Leadership. SC Johnson College of Business. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.johnson.cornell.edu/programs/emba/healthcare-leadership/ .

CVS Health. Fellowship for Value-Based Care Leadership. Oak Street Health. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.oakstreethealth.com/careers/fellowship-for-value-based-care-leadership .

American Medical Association. RVS Update Committee (RUC) Information. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc .

American Medical Association. The CPT® Code Process. Updated July 7, 2025. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/cpt-editorial-panel/cpt-code-process .

ABC News. ABC News Medical Unit. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://abcnewsmedunit.com/ .

Association of American Medical Colleges. Public Health Pathways for Medical Students. AMA Students and Residents. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/attending-medical-school/article/public-health-pathways-2 .

U.S. News and World Report. The Best Public Health Schools, Ranked in 2025. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-health-schools/public-health-rankings

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Nominate a New U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Member. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/cpi/about/otherwebsites/uspstf/nominate.html

Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19 — Navigating the Uncharted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1268–1269. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejme2002387

Mou D, Sarma A, Sethi R, Merryman R. The State of Health Policy Education in U.S. Medical Schools. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(10):e19. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1101603 .

Malik B, Ojha U, Khan H, Begum F, Khan H, Malik Q. Medical Student Involvement in Health Policy Roles. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:735-743. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.s147212 .

Haque M, A Rahman NA, Rahman S, et al. Medical Students’ Perception Regarding Health Policy Teaching and Their Participation in Health Policy Roles: A Survey at a Public University in Malaysia. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(6):967. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10060967 .

Greysen SR, Wassermann T, Payne P, Mullan F. Teaching Health Policy to Residents —Three-Year Experience with a Multi-Specialty Curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1322–1326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1143-1 .

Patel MS, Lypson ML, Miller DD, Davis MM. A Framework for Evaluating Student Perceptions of Health Policy Training in Medical School. Acad Med. 2014;89(10):1375–1379. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000408

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Milestones by Specialty. ACGME. Accessed March 26, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/milestones/milestones-by-specialty/ .

Gonzalo JD, Dekhtyar M, Starr SR, et al. Health Systems Science Curricula in Undergraduate Medical Education: Identifying and Defining a Potential Curricular Framework. Acad Med. 2017;92(1):123–131. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001177

Rowe RJ, Bahner I, Belovich AN, et al. Evolution and Revolution in Medical Education: Health System Sciences (HSS). Med.Sci.Educ. 2021;31: 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01166-x

Gonzalo JD, Chang A, Dekhtyar M, Starr SR, Holmboe E, Wolpaw DR. Health Systems Science in Medical Education: Unifying the Components to Catalyze Transformation. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1362–1372. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003400

Walton R, Greenberg A, Ehlke D, Solá O. Development of a Health Policy Elective for Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study. PRiMER. 2020;4:29. https://doi.org/10.22454/PRiMER.2020.557079

Emil S, Nagurney JM, Mok E, Prislin MD. Attitudes and Knowledge Regarding Health Care Policy and Systems: A Survey of Medical Students in Ontario and California. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E288–E294. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20130094

Liepert AE, Beilke S, Leverson G, Sheehy AM. Health Policy Advocacy Engagement: A Physician Survey. WMJ. 2021;120(1):29–33. PMID 33974762

Goetz C, Arora VM, Press VG. Teaching Health Policy to Residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):382–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1267-3

Crosson FJ, Levine SL, Ross MN. Health Policy Education for Medical Students: Time to Rethink? Perm J. 2023;27(3):1–4. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/23.045

Chimonas S, Mamoor M, Kaltenboeck A, Korenstein D. The Future of Physician Advocacy: A Survey of U.S. Medical Students. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):399. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/23.045 10.1186/s12909-021-02830-5

Clithero-Eridon A, Albright D, Brayfield C, Abeyta N, Armitage K. Students of Change: Health Policy in Action. Fam Med. 2022;54(1):38–43. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2022.598895 .

Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Standards, Publications, and Notification Forms. LCME. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://lcme.org/publications/ .

American Medical Association. AMA Homepage. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/ .

American Medical Association. Resident & Fellow Section (RFS) Leadership Opportunities. American Medical Association. Published August 21, 2023. Updated August 21, 2025. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/member-groups-sections/residents-fellows/resident-fellow-leadership-opportunities .

American Medical Association. Young Physicians Section (YPS) Leadership Opportunities. American Medical Association. Published August 1, 2023. Updated July 28. 2025. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/member-groups-sections/young-physicians/young-physicians-section-yps-leadership-opportunities .

American Medical Association. Member Organizations of the AMA House of Delegates. American Medical Association. Published August 4, 2023. Updated July 1, 2025. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/house-delegates/hod-organization/member-organizations-ama-house-delegates .

American Medical Association. State Advocacy Summit. American Medical Association. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/events/state-advocacy-summit .

Physicians Grassroots Network. Physicians Grassroots Network Homepage. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://physiciansgrassrootsnetwork.org/

Internships. Representative Kevin McCarthy. Published January 3, 2023. Accessed August 21, 2023. http://kevinmccarthy.house.gov/services/internships

Shen MR, Tzioumis E, Andersen E, et al. Impact of Mentoring on Academic Career Success for Women in Medicine: A Systematic Review. Acad Med. 2022;97(3):444–458. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000004563

Salata RA, Geraci MW, Rockey DC, et al. U.S. Physician-Scientist Workforce in the 21st Century: Recommendations to Attract and Sustain the Pipeline. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):565–573. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001950

The Center for Professionalism and Value in Health Care. Visiting Scholars. The Center for Professionalism and Value in Health Care. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://professionalismandvalue.org/visiting-scholars/ .

Darves B. Physician Mentorship: Why It’s Important, and How to Find and Sustain Relationships. NEJM CareerCenter Resources. February 28, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://resources.nejmcareercenter.org/article/physician-mentorship-why-its-important-and-how-to-find-and-sustain-relationships/ .

National Association of County and City Health Officials. Directory of Local Health Departments. NACCHO. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.naccho.org/membership/lhd-directory?searchType=standard&lhd-state=LA .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Short-Term Internships for Students. CDC Fellowships and Training Opportunities. Updated September 24, 2024. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/fellowships/php/opportunities/short-term.html .

American Medical Association. Public Health Pathways for Medical Students. Students and Residents. American Medical Association. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/attending-medical-school/article/public-health-pathways-2 .

Khatana SA, Patton EW, Sanghavi DM. Public Policy and Physician Involvement: Removing Barriers, Enhancing Impact. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.07 .020

AMPAC. AMPAC Candidate Workshop. AMPAC. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ampaconline.org/political-education/ampac-candidate-workshop .

National Clinician Scholars Program. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://nationalcsp.org/ .

National Institutes of Health. Medical Research Scholars Program. NIH Office of Clinical Research Training and Medical Education. National Institutes of Health. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cc.nih.gov/training/mrsp .

National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine. NLM Division of Intramural Research Program — Training Opportunities. National Institutes of Health. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/training.html# .

National Academy of Medicine. Emerging Leaders in Health and Medicine. National Academy of Medicine. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://nam.edu/programs/emerging-leaders-forum/ .

American Association for Physician Leadership. Fellowship in the American Association for Physician Leadership (FAAPL). American Association for Physician Leadership. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.physicianleaders.org/credentials/fellowship.

American College of Physicians. Certificate in Physician Leadership. American College of Physicians. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.acponline.org/meetings-courses .

Stanford Medicine. Physician Leadership Certificate Program. Stanford Medicine. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://med.stanford.edu/cme/featured-programs/physicianleadership.html .

The Health Management Academy. Physician Leadership Program. The Health Management Academy. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://hmacademy.com/physician-leadership-program/ .

Boston Children’s Hospital. Emerging Physician Leadership Program (EPLP). Boston Children’s Hospital Center for Educational Excellence and Innovation. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://dme.childrenshospital.org/courses/emerging-physician-leadership-program-eplp//

Turner AD, Stawicki SP, Guo WA. Competitive Advantage of MBA for Physician Executives: A Systematic Literature Review. World J Surg. 2018;42(6):1655–1665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4370-3

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/programs-and-institutions/programs/common-program-requirements/ .

The Center for Professionalism and Value in Health Care. Visiting Scholars. The Center for Professionalism and Value in Health Care. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://professionalismandvalue.org/visiting-scholars/ .

Denis JL, van Gestel N. Medical Doctors in Healthcare Leadership: Theoretical and Practical Challenges. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16 (Suppl 2): 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1392-8 .

Bitton A. Physician Hybridity in Primary Care. Published online May 2022.

American Medical Association. About the Council on Legislation (COL). American Medical Association. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/councils/council-legislation/about-council-legislation-col .

American Medical Association. AMA Elections. American Medical Association. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/house-delegates/ama-elections

Oliver D. How Much Influence Can Doctors Have Over Health Policy? BMJ 2022;376:o365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o365

Association of American Medical Colleges. Careers in Medical Research. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/medical-careers/careers-medical-research .

Saxena A, Meschino D, Hazelton L, et al. Power and Physician Leadership. BMJ Leader.2019;3:92–98. https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2019-000139

American Academy of Family Physicians. Join an FMIG. American Academy of Family Physicians. https://www.aafp.org/students-residents/medical-students/fmig.html .

Physicians for a National Health Program. About Us. Physicians for a National Health Program. https://pnhp.org/about/ .

Doctors for America. About Us. Doctors for America. https://doctorsforamerica.org/about/ .

Committee of Interns and Residents. About Us. Committee of Interns and Residents. https://www.cirseiu.org/about/ .

Robert Graham Center. Robert Graham Center Visiting Scholars and Fellows. Robert Graham Center. https://www.graham-center.org/scholars-fellows.html .

American Board of Family Medicine. Visiting Scholars Program. American Board of Family Medicine. https://www.theabfm.org/research/visiting-scholars-program/ .

Peter G. Peterson Foundation. About. Peter G. Peterson Foundation. https://www.pgpf.org/about/ .

Brookings. The David M. Rubenstein Fellows. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/david-m-rubenstein-fellowship-program/ .

The Commonwealth Fund. Fellowships. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/fellowships .

Centers for Disease Control. Fellowships and Training Opportunities. Centers for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/fellowships/php/index.html .

National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. Medical Research Scholars Program. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cc.nih.gov/training/mrsp .

Clinical Scholars. Meet the Fellows. Clinical Scholars. https://clinicalscholarsnli.org/fellows/ .

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Summer Health Professions Education Program. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.shpep.org/ .

American Academy of Family Physicians. Emerging Leader Institute. Academy of Family Physicians. https://www.aafpfoundation.org/our-programs/education-initiatives/family-medicine-leads-emerging-leader-application.html .

American Association of Medical Colleges. Leadership Development. American Association of Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/learn-network/leadership-development .

American College of Healthcare Executives. Physician Leadership. American College of Healthcare Executives. https://www.ache.org/membership/physician-leader .

American College of Physicians. Global Physician Scholar (GPS) Program. American College of Physicians. https://www.acponline.org/about-acp/acp-global-engagement/global-physician-scholar-gps-program .

American Public Health Association. APHA Internships and Fellowships. American Public Health Association. https://www.apha.org/professional-development/apha-internships-and-fellowships .

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Scientific Internships, Fellowships\Trainees and Non-U.S. Citizens. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/jobs-and-training-fda/scientific-internships-fellowships-trainees-and-non-us-citizens .

Appendix