As physicians, many of us like to consider ourselves innovators and, occasionally, entrepreneurs. How many times have you recognized a novel item or approach in your professional or personal life and said to yourself, “Darn, I thought of that five years ago. I should have done something about it back then ... oh, well, another missed opportunity.”

Once upon a time, I was fortunate to have been involved with leading-edge NASA-funded telemedicine research. We were doing some pretty cool telehealth and remote sensor monitoring things that were quite far ahead of the curve of telemedicine at the time. Occasionally during the pandemic’s peak, I admit I had fleeting thoughts about what it would have been like had I stayed on a career path in telehealth. The opportunity was there back in the day ... oh, well!

What about your missed opportunities or not-yet- realized innovations? Anything in leadership?

Disruptive innovation has been in the business lexicon for several years. The literature is replete with theory and benefits related to this form of innovation. For healthcare, in my opinion, stating “patient-centered care is of highest priority” is a different form of disruptive innovation. It is disruptive because, as an industry, we find it terrifically difficult to consistently innovate the delivery of truly patient-centered care over a sustained period across multiple environments. Yes, there are pockets of successful examples, but the hoped-for eventual outcome remains elusive.

Per the generic trajectory for disruptive innovation outlined in Figure 1, our industry seems stuck somewhere between stages 2 and 3. Innovation is happening, but it is not yet meeting patients’ needs, neither have innovative replacement models and disruptive approaches yet fully arrived or succeeded.

Figure 1. Trajectory for Disruptive Innovation. From MIT Sloan Management Review (Vol. 57, Issue 1).

This remains an important challenge and opportunity for physician leadership.

All physicians are leaders at some level, so we can individually and collectively continue to provide the leadership to achieve true patient-centered care in our industry. To do so, however, we must develop our connectedness to leadership and maintain our empathy as physicians.

Rose Perry and Stephen Braren, in their blog, The Creature Times, “Social Connectedness 101: Defining Social Connectedness,”(1) broadly defined “social connectedness” (also referred to as “social connection”) as a state of feeling close (or “connected”) to another person or other people. This includes feeling cared about by others (and caring about others), as well as a feeling of belonging to a group or community.

An important component of this definition is that social connectedness is “subjective” and therefore based on an individual’s perception of connection. This is distinct from “objective” features of an individual’s social environment, such as the size of their social network or how the network functions to provide them with social support.

Similarly, Helen Riess, MD, in her Journal of Patient Experience article “The Science of Empathy,”(2) describes how “empathy plays a critical interpersonal and societal role, enabling sharing of experiences, needs, and desires between individuals and providing an emotional bridge that promotes pro-social behavior.”

In the past, empathy was considered an inborn trait that could not be taught, but research has shown that this vital human competency is mutable and can be taught to healthcare providers. Riess reports that studies show empathy declines during medical training, and that without targeted interventions, uncompassionate care and treatment devoid of empathy results in dissatisfied patients who are unlikely to follow through with treatment recommendations, resulting in poorer health outcomes and damaged trust in health provider relationships.

Empathic medical care is associated with many benefits,(3) including improved patient experiences, adherence to treatment recommendations, better clinical outcomes, fewer medical errors and malpractice claims, and higher physician retention.

A recent column by Elizabeth Toll and Christine Sinsky on “The Deep Work of Doctoring — Prioritizing Relationships in Medicine”(4) highlights several important contemporary healthcare issues and pressures needing alternative approaches. As they state, “... bedrock of this vision is strong relationships with patients, families, and colleagues. Shared historical experience and knowledge help patients and physicians face unknowns and uncertainty together, resulting in streamlined workups, better outcomes, and enduring connections that nurture our patients and ourselves.” They go on to provide five core elements of focus that may help augment this vision:

1. Strong Relationships

Maximize patient continuity with own physician.

Value and record the patient’s story; use algorithms and templates selectively and allow free-text additions.

Build stable and uptrained teams.

Promote colleague relationships by co-locating teams and maximizing face-to- face communication.

2. Trust

Promote continuity of care in outpatient and inpatient settings.

Value and protect patient-physician confidentiality.

3. Undivided Attention

Support systems that promote clinicians’ undivided attention.

Establish etiquette around disruptions such as secure chat; allow physicians to turn off intrusions during clinical care.

Optimize electronic health records to minimize multitasking.

4. Problem-Solving

Seek commitment by all stakeholders to decrease administrative burden and unnecessary regulations, policies, and requirements.

Optimize redistribution of work, including inbox and care documentation to stable, co-located teams.

Build flexibility into schedules to allow time for problem-solving, communication with colleagues, and information-seeking.

Encourage patient involvement through shared decision-making, shared clinic notes, and patient contributions to their charts.

5. Time

Build realistic, flexible schedules.

Schedule visit length to be commensurate with scheduled care.

Ensure adequate staffing ratios; practice team sharing of work.

Connectedness, empathy, and relationships, when brought together, become a strong formula to potentially leverage true patient-centered care, to re-invigorate the professional joy of practicing medicine, and to make the deep work of doctoring satisfying for all.

Connectedness to physician leadership potential is equally critical in this paradigm. Physicians and the patient-physician relationship remain the dominant driver of today’s healthcare industry. Strong leadership, therefore, regardless of professional level or titled vs. non-titled roles, makes it possible to augment relationships and to further reinforce empathy in a kind, respectful, and meaningful fashion with and for others (and oneself ). But leadership is not just a happenstance for physicians; we just don’t get trained in this realm.

In “A Theory of Expert Leadership,”(5) Amanda Goodall suggests that “organizations perform more effectively when led by individuals who have a deep understanding of the core business of their organization. Being a capable general manager is not sufficient. Expert leaders are those with 1) inherent knowledge, acquired through technical expertise combined with high ability in the core-business activity; 2) industry experience, which stems from time and practice within the core-business industry; and 3) leadership capabilities, which include management skills and a leader’s innate characteristics.”

Goodall says that “expert leaders use industry knowledge to make strategic decisions, and their credentials and experience give them greater credibility with followers” based on three dimensions: inherent knowledge, industry experience, and leadership capabilities. She further demonstrated the benefits of physician leadership(5) on standard quality metrics and outcomes when hospitals have a physician as CEO.

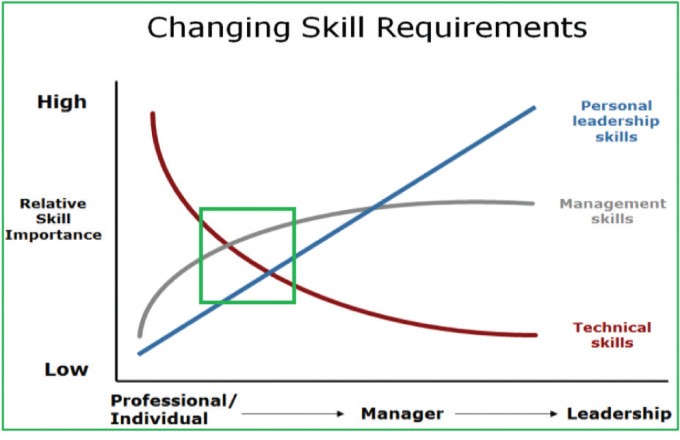

All physicians exhibit some degree of managerial and leadership skills regardless of clinical specialty (technical skills) received from their training. Figure 2 profiles the trajectory of how others view the importance of physicians’ skills as they shift toward management and leadership.

Figure 2. The Importance of Skills Over Time

In early-phase career time, physicians are predominantly viewed as clinicians with specific skills. Over time, regardless of practice environment or administrative responsibilities, physicians are expected to mature and gain management and leadership skills. Eventually, a relative minority will leave their clinical path and remain focused predominantly on management or leadership itself.

The green box in Figure 2 demonstrates where most physicians lie in terms of the constellation of skills being utilized in their professional lives; however, a high degree of expertise in all areas is necessary for patient-centered care to emerge more fully.

ONGOING RESEARCH

Interestingly, a recent systematic literature review(6) of physician leadership through the lens of expert leadership produced a paucity of highly relevant articles. The initial search led to 3,581 studies over a 10-year period. After removing duplicates, the remaining set of studies totaled 3,052. After further review and analysis, the authors’ systematic review included 12 studies with seven quantitative studies (58.3%), three qualitative studies (25%), and two mixed-method studies (16.7%).

Of the 12 studies reviewed in full detail, five targeted the organizational-level outcomes of physician leadership, focusing on a population of either a hospital, health system, or accountable care organization (ACO). The outcomes explored in these articles included quality scores, patient health outcomes, management scores, financial performance, operational efficiency, successful change initiatives, advanced care management, and information technology capabilities. Three of the remaining articles targeted individual-level outcomes, focusing on individual physicians and individuals reporting to them.

Outcomes of physician leadership explored in these latter articles included job satisfaction, leadership effectiveness, and leader identity. One article examined both individual and team-level outcomes associated with physician leadership, focusing on burnout and job satisfaction at both the individual and department levels. The two remaining articles targeted team-level outcomes such as team project success and team effectiveness.

In terms of level of physician leadership, two articles explored the impact of physician leadership at the CEO level, and the remaining articles covered physician leaders in formal leadership roles of varying levels.

Reviewing the details of this analysis provides insightful information beyond the scope of this column; however, AAPL recognizes the importance of doing further research on the impact, outcomes, and benefits provided by physician leadership. Current AAPL-funded projects are reviewing the literature to provide a retrospective of the outcomes for our AAPL Certified Physician Executive (CPE) alumni and AAPL Fellows. Following these studies, our commitment is to be proactive with research on the benefits and impacts of physician leadership in healthcare across a broad spectrum.

TOWARD POSITIVE TRANSFORMATION

Physician leaders can nudge, disrupt, and innovate true patient-centered care toward a combination of stages 3 and 4 in Figure 1. The industry depends on physicians in many ways; patients and families depend even more on physicians to provide and deliver on the benefits of our inherent leadership for better care and improved care systems. Our relationships with peers and co-workers are equally dependent on our empathic leadership.

The medical profession is still viewed as a leadership profession, not only by our industry, but also by society in general; therefore, as physician leaders, we must embrace the complexities of our industry. By consolidating our connectedness, augmenting our empathy, and expanding our relationships, we can take advantage of the opportunities in which our individual and collective energies achieve the positive transformation needed for our industry.

Remember, leading and contributing to significant positive change is our overall intent as physicians. AAPL focuses on maximizing the potential of physician-led, inter-professional leadership to create personal and organizational transformation that benefits patient outcomes, improves workforce wellness, and refines the delivery of healthcare internationally.

Through this AAPL community, we all can continue to seek deeper levels of professional and personal development, and to recognize ways we can each generate constructive influence at all levels. As physician leaders, let us become more engaged, stay engaged, and help others to become engaged. Exploring and creating opportunities for broader levels of positive transformation in healthcare is within our reach —individually and collectively.

REFERENCES

Perry R, Braren S. Social Connectedness 101: Defining Social Connectedness. The Creature Times. https://www.thesocialcreatures.org/thecreaturetimes

Riess H. The Science of Empathy. Journal of Patient Experience. 2017;4(2):74–77. https://doi.org/10 .1177/2374373517699267

Riess H, Kelley JM, Bailey RW. et al. Empathy Training for Resident Physicians: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Neuroscience-Informed Curriculum. J Gen Intern Med .2012; 27:1280–1286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2063-z

Toll ET, Sinsky CA. The Deep Work of Doctoring—Prioritizing Relationships in Medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(9):904–905. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.3012

Goodall AH. A Theory of Expert Leadership. Discussion Paper No. 6566. Institute for the Study of Labor. May 2012. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2066989

Thoebes GP, Porter TH, Peck JA, et al. Physicians as Leaders: A Systematic Review Through the Lens of Expert Leadership. Leadership in Health Services. July 2023. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-02-2023-0008