Physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs) are increasingly being asked to assume leadership roles in healthcare systems, and leadership development programs are recognized as essential for success in these roles.(1-3) A high percentage of academic health centers now offer formal leadership development programs delivered by internal faculty.(4)

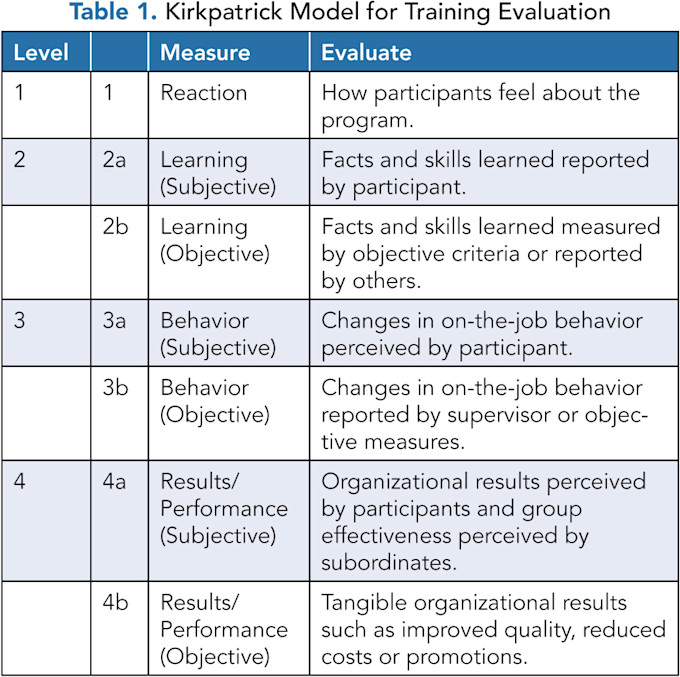

The Kirkpatrick model is a recognized method for the evaluation of training and learning programs (Table 1). While there are other models for evaluating training, such as the Phillips ROI Model and Kaufman’s Five Levels of Evaluation, we chose to use the Kirkpatrick model for consistency and comparison because other published reports of physician leadership training have referred to this model.

Many programs have shown improved provider self-awareness, improved knowledge, and better teamwork, which fall into Kirkpatrick categories 1, 2, and 3.(5) Improved wellness and decreased physician burnout have also been documented.(6) Organizational benefits (Kirkpatrick 4b) are less commonly identified with objective metrics, and there has been limited examination of the benefit of capstone projects incorporated into leadership development programs.

We previously reported on the Physician and APP Leadership Development Program at Inova Schar Heart and Vascular, showing level 4b organizational benefits through ascent of participants to higher levels of leadership and responsibility in the health system.(7) For the current review, we examined the organizational benefit of the capstone projects developed by five successive cohorts of participants in our training program.

THE INOVA SCHAR HEART AND VASCULAR’S PHYSICIAN AND APP LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM

In 2015, the health system recognized the need for provider leadership development. We structured a leadership development program based on a review of successful programs at other healthcare systems and academic institutions and designed to meet the specific needs of clinical leaders in our organization. The program was focused on physicians and later on APPs in the health system’s heart and vascular service line. The program was proposed and launched at the service line level because of both fiscal constraints and support from service line leadership. It is now expanding to be a systemwide program.

The first cohort consisted of physicians nominated by health system leaders. For subsequent cohorts, a general call for applications to participate was issued to all physicians and, starting with cohort 5, APPs working within the heart and vascular service line. Selection to the program was made by the program director based on applicants’ answers to a series of questions focused on what they hoped to gain from the program and how they hoped to improve healthcare delivery, quality, or operational efficiencies.

As previously reported,(7) the training program consists of seven full-day didactic sessions, facilitated by faculty from the American Association for Physician Leadership (AAPL), held over a 10-month period. The curriculum covers the core competencies of leadership with a focus on adaptive skills, improved introspection, and self-awareness, with some didactic sessions addressing gaps in technical skills.

Self-assessment tools such as the Maslach Burnout Survey (MBI), California Psychological Inventory (CPI 260), and DiSC® were used to help participants understand their own personality types and behavioral styles as well as appreciate the strengths and challenges for people with different combinations of personality and behavioral traits.

Additional evening sessions facilitated by health system faculty were used to supplement the didactic content covered during the full-day sessions. A full range of technical leadership topics, communication, healthcare finance, and health law were covered, and books focused on leadership and organizational transformation were assigned and discussed.

Participants met regularly with an administrative mentor. The program culminated with each participant presenting a final capstone project at a session attended by health system leadership. The participants were given broad discretion in selecting a project and were guided through the process by their mentors. All capstones were completed within the timeframe of each cohort’s program. Some were proposals for projects that were later implemented. Beginning with cohort 5, pre- and post-program competency assessments developed with AAPL were administered to objectively evaluate the program’s impact.

CAPSTONE PROJECT ASSESSMENTS

Seventy-eight capstone projects were completed and presented at the conclusion of cohorts 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6. Cohort 4 was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, and face-to-face meetings were not possible. Our standard leadership program format is not amenable to a virtual format, given the importance of interpersonal connectivity, so an entirely different web-based program led by Stephen Beeson, known as the Clinician Experience Project, was implemented.(8) This allowed for a much larger cohort of providers and administrators, but much less personal engagement, and there were no capstone or team projects included in that program.

A Capstone Project Review Committee was formed, comprising the health system chief financial officer, the chief medical officer, and the vice president and administrator of the heart and vascular service line.

The committee reviewed each project based on six criteria, and many projects met multiple criteria of success. Three criteria are objective and are easily measurable, and three are subjective. The three objective criteria are:

The project was implemented either as a beta test or a fully implemented program or process in the health system.

The project resulted in either a publication or a presentation at the meeting of a professional society. In-service presentations are not included.

The mentee took on greater responsibility or leadership in the health system. This was self-reported and included a change in title, a recognized leadership position, or a documented increase in areas of responsibility.

The three subjective criteria were:

The project led to improved clinical quality or improved access to care as judged by the committee based upon proven efficiencies, additional new programs, or reduced length of stay or complications.

The project improved the reputation and branding of the health system in the professional and general community. This included new or improved programs marketed to the community, additional services, and improved outcomes shared with the professional community and community-based programs.

The project resulted in a financial benefit to the health system, where financial benefit was defined as the inclusion of a financial report showing profitability, a new program that generated new revenue, or evidence that the project resulted in reduced complications or reduced length of stay for patients.

RESULTS

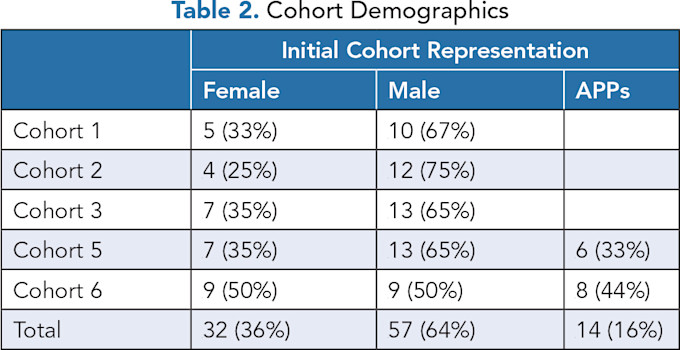

Eighty-nine participants were enrolled in the five cohorts; 78 completed the program and presented their capstone projects. The nine participants who did not complete a capstone either dropped out of the program for personal reasons, left the health system, or deferred their participation to a later cohort. Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 were composed solely of physicians, while cohorts 5 and 6 had 33% and 40% APPs, respectively. Sixty-three capstone projects were presented by physicians and 10 by APPs. Cohort demographics are found in Table 2.

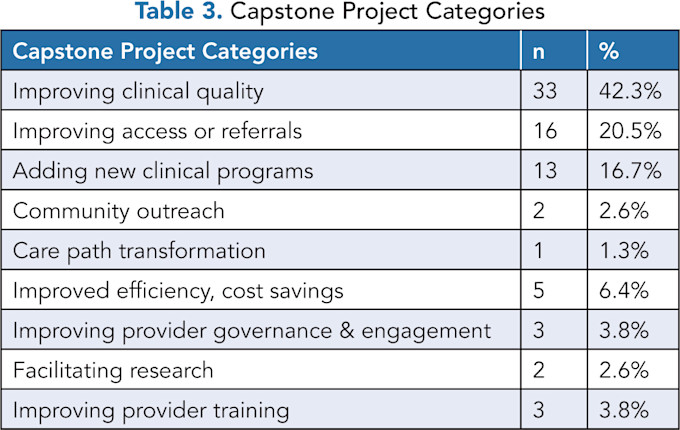

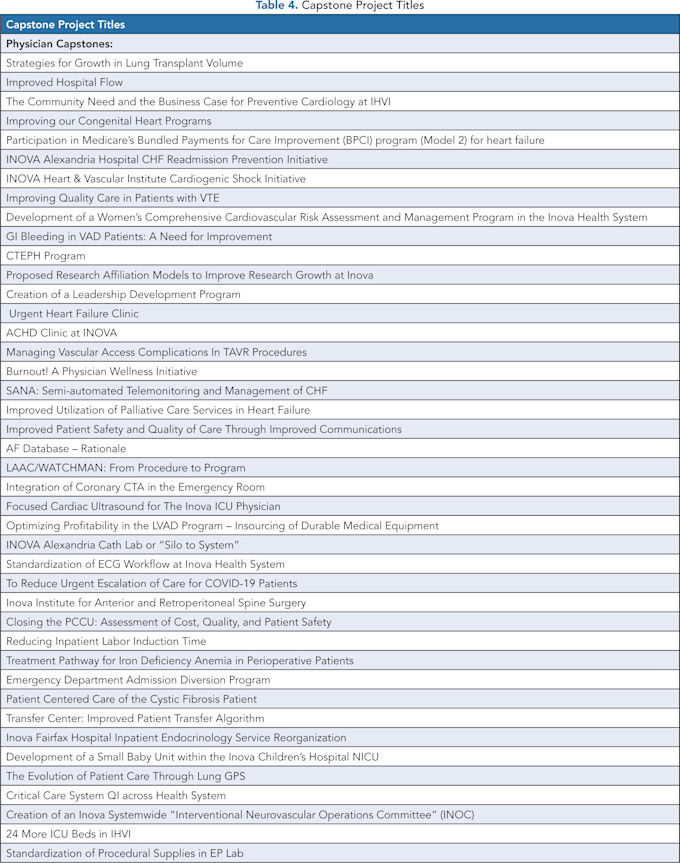

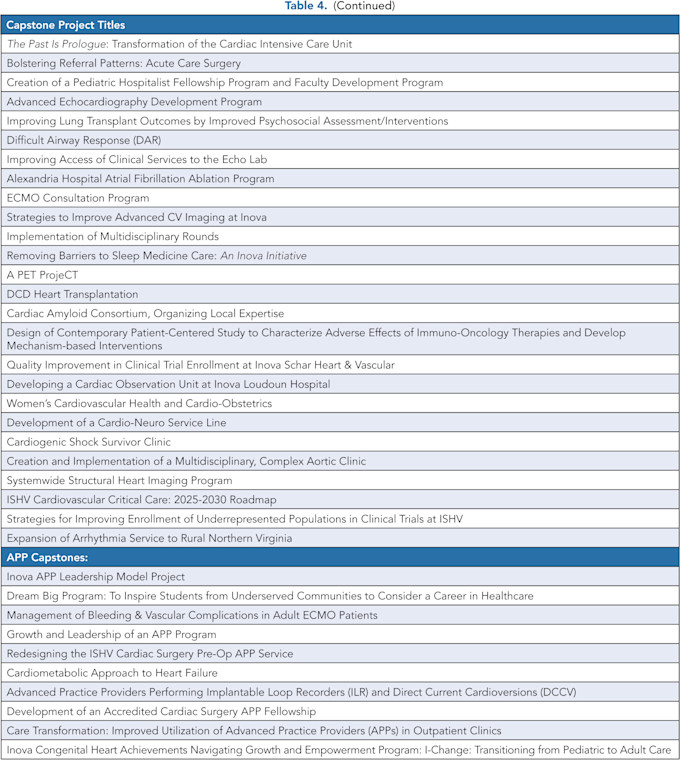

Capstone projects were categorized as follows: 42% improving clinical quality, 20% improving access or referrals, 17% adding new clinical programs, 6% improving efficiency or cost savings, and smaller percentages addressing provider education, research, governance, community outreach, and care path transformation (Table 3). The titles of all the capstone projects can be found in Table 4.

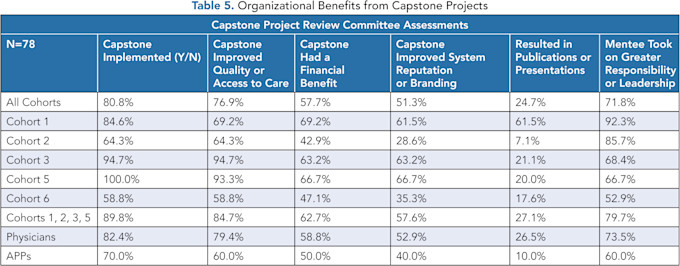

Objective measurements showed that 81% were implemented in either a beta test format or permanent activation; 72% of mentees took on greater responsibility or leadership in the health system, and 25% of the projects resulted in either a publication or professional presentation.

For cohorts 1, 2, 3, and 5, 48 of 53 (90%) capstones that were implemented remained active programs or projects two years following their presentation. The Capstone Project Review Committee found that 77% of all projects submitted improved clinical quality or improved access to care, 58% resulted in a financial benefit to the health system, and 51% improved the health system’s professional and community reputation or branding (Table 5).

All six of these results represent organizational, Kirkpatrick level 4a and 4b outcomes that benefit the sponsoring enterprise. The three subjective criteria, which are categorized as Kirkpatrick 4a benefits, could be 4b benefits with appropriate objective metrics. It was not a priori intended to evaluate the impact of these capstones, and no data-capture system was implemented before this review.

The numbers are too small for meaningful subgroup analysis (14 APPs and 75 physicians), but the physicians scored higher than APPs in all categories.

The percentage of positive outcomes increases if cohort 6 is excluded from the review, as they completed the program most recently, and some outcomes are not yet available for evaluation. For cohorts 1, 2, 3, and 5, 90% of capstone projects were implemented, 85% improved quality or access, 63% brought a financial benefit to the health system, the results of 27% were either published or presented at professional meetings, and 80% of mentees took on greater responsibility or higher leadership positions (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Physician and advanced practice provider leadership development programs have been widely adopted across many healthcare organizations and are considered critical to high-quality healthcare delivery. The benefits of these programs have often focused on Kirkpatrick levels 1, 2, and 3 outcomes, related to participant impressions, objective and subjective measures of skills and knowledge, and changes in on-the-job behavior. There has been less focus on organizational benefits (Kirkpatrick level 4).

Most earlier reviews of outcomes of physician leadership programs focused on subjective criteria. Frich, et al., presented a review of the literature on leadership development programs in 2015.(9) Forty-five programs were identified, 35 of which were exclusively for physicians. Positive outcomes were reported in all studies, but for most programs, this was based on self-reported satisfaction and knowledge. Six studies documented favorable organizational outcomes, mostly as assessed by clinical measures.

Kirkpatrick level 4b, an objective, tangible impact upon the organization, was reported by only 5 of the 45 studies. Stroller later reviewed several meta-analyses of physician leadership programs in healthcare institutions.(2) Most of these studies only assessed the subjective learning of their participants. He reported that the Cleveland Clinic was among the few that evaluated the institutional benefit of their programs, and they showed a positive institutional impact related to both programmatic development and the leadership trajectories of participants.

When described, the organizational benefits of these programs have been documented to include a positive impact on culture; improved clinical quality and safety; improved leadership knowledge, insight, and skills among participants; and a positive impact on their leadership pipeline.(10) Debets, et al., recently reviewed more than 100 programs and outlined how the structure and content of various leadership development programs inform the organizational results.(11)

Research indicates that not just the didactic content of the program, but also its design and delivery have a significant impact on outcomes.(12,13) Lyons reviewed 117 published studies and found that programs that employed internal or mixed faculty were significantly more likely to report organizational outcomes than programs with only external faculty.(14) In addition, project work such as individual capstone projects or team-based projects and mentoring increased the likelihood of reporting organizational outcomes. No specific content was independently associated with beneficial organizational outcomes.

They conclude that while educational content is important, methods and program design are more important. They suggest that interventions should include projects and individual or group mentoring.

Angood reported on the AAPL Certified Physician Executive (CPE) program, noting self-reported organizational benefits including improved quality and safety, new program development, operational gains, cost savings, and leadership during a crisis.(15) He stated that leadership development programs’ impact on organizational outcomes depends not only on the composition of the program, but also on the “leadership ecosystem” within that organization.

There has been very little focus on the benefit to the organization of including capstone projects or team-based projects as part of leadership development programs. The Inova Schar Heart and Vascular leadership program has demonstrated Kirkpatrick level 1, 2, 3, and 4 benefits.(7)

Requiring a capstone project was believed to be critical to the learning process, although we did not know a priori whether the projects would benefit the health system. We considered requiring team-based projects similar to those required by other organizations to more realistically mirror real-life work, but we opted for individual projects to improve compliance.

We found that the capstone projects had a substantial benefit to the health system. Eighty-one percent of these projects were implemented, 77% improved quality or access, 25% were either published or presented at professional meetings, and it is estimated that 58% had a financial benefit for the system.

Our leadership development program now includes both physicians and APPs, which is an important and distinguishing feature. Most programs of this type include physicians only. We opted to include APPs because they are now more integrated into health system leadership, especially in the cardiovascular service line. Some APP-specific programs have been shown to benefit their organizations, but we felt that combining physicians and APPs in a joint program facilitates better team-based care and the development of successful dyad relationships and improves both quality and safety in the health system.(16-18)

LIMITATIONS

The Capstone Project Review Committee used both objective and subjective criteria to assess the six measured outcomes that we report. It was not possible to blind the review of the capstones because of the subject matter. We attempted to focus on all Kirkpatrick level 4b outcomes, although some would be categorized as 4a because of the subjectivity of these evaluations.

CONCLUSION

It has been well documented that individual capstone projects or team-based projects are important components of leadership development programs. Our organization has included the requirement for individual capstone projects across all six cohorts in this analysis. Our results have demonstrated the substantial benefit to the health system from these capstone projects in terms of improved care, better access, and reputation development, as well as a financial benefit to the organization. This provides data to support the continued financial investment in leadership development.

Strong, effective leaders are critical to successful health systems that deliver the highest-quality patient care. At this time, when health systems are experiencing financial challenges, it is important to remember that investing in our providers and their leadership development will deliver high-quality care and yield important dividends for our patients. Continued attention to the organizational benefits of leadership programs is important, and standard criteria to assess those benefits should be developed. With appropriate pre-project planning, objective assessment of individual and team-based capstone projects can better identify Kirkpatrick level 4b organizational benefits that are important to the sponsoring health systems.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Dwight and Martha Schar for their generous support of Inova Schar Heart and Vascular, the Dudley Family for their continued contributions and support of the Inova Dudley Family Center for Cardiovascular Innovation, and Elizabeth Wilson for editorial support.

REFERENCES

Lerman C, Jameson JL. Leadership Development in Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1862–1863. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1801610 .

Hill JL Jr, Conroy JM, Azocar RJ. From the Bedside to the Boardroom: Developing Physician Leaders to Manage Tomorrow’s Healthcare Challenges. Front Health Serv Manage. 2024;41(2):27–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/hap.0000000000000206 .

Stoller JK. Developing Physician Leaders: Does It Work? BMJ Lead. 2020;4:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2018-000116 .

Lucas R, Goldman EF, Scott AR, Dandar V. Leadership Development Programs at Academic Health Centers: Results of a National Survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):229–236. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001813 .

Kirkpatrick, DL. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. Berrett-Koehler;1994.

Briggs, SE, Heman-Ackah, SM, Hamilton, F. The Impact of Leadership Training on Burnout and Fulfillment Among Direct Reports. J Healthc Manag. 2024;69(6):402–413. https://doi.org/10.1097/jhm-d-23-00209 .

Levy WS, O’Connor CM. Five-Year Experience From a Cardiovascular Physician and Advanced Practice Providers Leadership-Development Program. J Card Fail. 2024;30(8):1052–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2024.03.013 .

Practicing Excellence. The Clinician Experience Project. https://knowledge.practicingexcellence.com/clinician-experience-project .

Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. Leadership Development Programs for Physicians: A Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):656–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1 .

Seidman G, Pascal L., McDonough J. What Benefits Do Healthcare Organisations Receive from Leadership and Management Development Programmes? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. BMJ Lead. 2020;4:21–36. https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2019-000141 .

Debets, M, Jansen I, Lombarts K, Kuijer-Siebelink W, Kruijthof K, et al. Linking Leadership Development Programs for Physicians with Organization-Level Outcomes: A Realist Review. BMC Health Serv Res. 23(1):783. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09811-y .

Throgmorton C, Mitchell T, Morley T, Snyder M. Evaluating a Physician Leadership Development Program — A Mixed Methods Approach. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30(3):390–407. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-11-2014-0187 .

Geerts JM, Goodall AH, Agius S. Evidence-Based Leadership Development for Physicians: A Systematic Literature Review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;246:112709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112709 .

Lyons O, George R, Galante JR, et al. Evidence-Based Medical Leadership Development: A Systematic Review. BMJ Lead. 2021;5(3):206–213. https://doi.org/10.1136/leader-2020-000360 .

Angood PB. “Profiles in Success”: Certified Physician Executives Share the Value and ROI of Their CPE Education. American Association for Physician Leadership. April 12, 2024. https://www.physicianleaders.org/articles/doi/10.55834/wp.8139640919.

Duke Health. Duke Advanced Practice Provider Leadership Institute. Duke University. https://sites.duke.edu/appli/ .

Stanford Medicine. Advanced Practice Provider Leadership Certificate Program. Stanford University. https://med.stanford.edu/content/sm/cme/featured-programs/APPleadership.html .

UCSF Health. Leadership Academy for the Advanced Practice Provider. University of California, San Francisco. https://nursingexcellence.ucsf.edu/leadership-academy-advanced-practice-provider .