Physician wellness is a clearly established factor for improving patient outcomes and experience and a national priority for the healthcare system. The recently released 2022 National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being highlights key priorities designed to improve the environment and culture for clinicians.(1) The plan specifically addresses burnout, described as a work-related stress reaction involving emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment.

The National Plan recommends multiple actions and identifies entities to maintain the function of the U.S. healthcare system. Physician input is needed to adequately assess and address potential organizational deficiencies and implement effective initiatives that reduce physician burnout.(2) However, evidence of the best method for eliciting physician input is lacking.

Surveys, which have previously been the mainstay of physician wellbeing assessments, add additional duties to already-overburdened physicians. Surveys often have low response rates, are subject to recall bias, and are not perceived as timely methods for planning for and assessing change as issues may have evolved.(3)

In addition, issues that affect physician wellness are highly related to specific operational units or cultures within a larger organization, making a single “validated” survey less useful to physician leaders.

The stressors physician leaders and physicians faced during the COVID-19 pandemic were unparalleled. Physicians’ work involved intense physical and emotional labor, long work hours, irregular shifts, and exposure to human suffering and death. The pandemic-related stress and increased workload led to a dramatic increase in physicians reporting burnout, rising from 38% in 2020 to 63% in 2021.(4)

AMA’s 2022 National Burnout Benchmarking report suggests that the prevalence of burnout among physicians may still be increasing.(5) The National Academy of Medicine and the Surgeon General have prioritized physician burnout as a public health crisis.(1) Physician leaders need a localized, specific means of collecting physician feedback and establishing bidirectional communication to address burnout effectively.

Development of the Intervention

The University of California San Diego Health System is a large public university medical center committed to an extraordinary culture of physician wellness. The Physician Wellness Office was established in 2021. Each clinical department is allocated funds to support physicians who serve as department wellness directors (DWDs). In collaboration with the department chairs, the DWDs are responsible for their department’s physician wellness plan, which identifies and addresses local stressors.

The institution has outlined role descriptions and funded time to support DWD physician wellness work. Individuals in the DWD role also coordinate efforts and best practices throughout the institution by way of a multi-departmental DWD committee that meets monthly. With variations across departments, DWDs also conduct periodic, informal listening sessions that may include a social event (e.g., happy hours, hosted dinners, etc.), which deepens a sense of community and connection.

To ensure that all physicians in their respective departments were able to contribute their perspective to physician wellness efforts, DWDs conducted a feasibility pilot of department-based, small-group, physician-facilitated, physician-only discussions (PODs) to assess whether this framework would provide more rapid bidirectional communication and promote a wellness culture.

Four of 18 departments participated in this feasibility initiative to provide an opportunity for direct physician input regarding wellness issues, identify and share actionable items for timely improvement with the institutional leadership, and build a sense of professional community with shared communication and support.

The intervention was designed to provide departmental flexibility and ensure that the POD meetings fit the departmental culture. Each departmental wellness leader was given broad recommendations to form small groups of < 20 physicians who would meet for at least 15 minutes, preferably without additional time commitment (i.e., scheduled when participating physicians would otherwise meet). Most groups met for longer than 15 minutes, although the time was not tracked. Most groups ranged in size from eight to 12 physicians. POD logistics can be found in Table 1.

Description of the Intervention

Four clinical departments within a large public university medical center with established wellness programs (anesthesiology, emergency medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics) conducted POD meetings. Individual department wellness directors recruited POD facilitators who received one hour of training by communication experts on strategies for engaging participants, establishing a psychologically safe environment, limiting toxic and non-productive conversation, and identifying group priorities.

Table 2 displays the departmental wellness initiatives in place before the PODs initiative. Before the first POD meeting, each department implemented a strategy to promote discussion. The Departments of Anesthesiology and Emergency Medicine sent a one-question, anonymous survey asking faculty members about their “top” wellness concerns (~60% response rate).

The Department of Family Medicine supplied participants with a document featuring physician suggestions for improvement based on one-on-one interviews conducted by the DWD with various faculty physicians. In addition, a baseline survey conducted before the first PODs demonstrated that two-thirds of respondents reported positive signs of engagement and alignment, with a burnout rate of 29%.

The Department of Pediatrics encouraged its faculty via department-wide communication to use an anonymous suggestion box on the department website to submit questions or topics for discussion in PODs.

Following the first POD meeting, the facilitators shared with the DWD findings regarding wellness concerns. Themes were identified and linked to recommendations for action. Subsequent POD debrief sessions between the DWDs and their department chair culminated in proposed action plans with prioritized physician wellness initiatives.

Results

The POD meetings were perceived as successful in all departments. Participants and leaders described POD meetings as a valuable step in facilitating meaningful engagement and bidirectional communication between physicians and leaders. The general consensus among POD leaders was that the facilitation training was adequate to lead the groups effectively. In some departments, follow-up was provided to POD facilitators through virtual meetings and the distribution of tip sheets to further troubleshoot or answer questions regarding the optimal facilitation of PODs.

A consistent theme among participating physicians was the desire for demonstrable action following the POD meetings. In response, corresponding action plans were developed and refined with a specific implementation timeline. This highlights the need for closed-loop communication, which follow-up POD meetings provide, ensuring that participants see that their concerns and requests were heard and addressed.

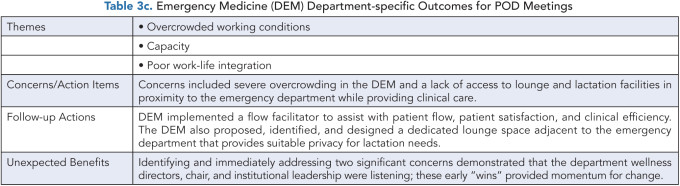

Tables 3a-d report the department-specific outcomes for POD meetings. All participating departments used a small-group format not organized by academic division. Key themes consistent with previously described drivers of burnout emerged from POD meetings across multiple pilot departments.(6)

These common themes included improving clinical workload and workflow (in four departments), a desire for a sense of community (in three departments), aligning and balancing academic and clinical missions (in three departments), work-life integration (in two departments), and enhancing information technology/electronic medical record efficiency (in two departments). Table 2 captures aspects that were unique to the individual departments.

Feedback on the POD meetings was generally positive, with physicians expressing appreciation for the opportunity to gather, connect, and discuss issues. Although formal feedback was not solicited post-POD, oral feedback was provided at the time of POD meeting completion.

Physician comments included that “PODs send the message that individual voices are important to the department” and that they “allow crosstalk among members of different divisions/ranks/goals.” This experience is consistent with prior findings that self-facilitated physician, small-group meetings can reduce social isolation and build a sense of community, both of which contribute to decreased burnout.

Next Steps

Physician leaders responded positively to the POD framework, perceiving the meetings as an innovative wellness initiative with a robust mechanism for physician engagement that builds on prior evidence highlighting the importance of professional community, closed-loop communication, and institutional responsiveness.

This lean and cost-effective process provided a feasible framework for on-the-ground physicians to identify ongoing systems issues affecting physician mental health and wellness while obtaining support and alignment from physician peers.

As emphasized by participating physicians, identifying actionable items is the key to continuing the momentum of POD meetings. The four participating departments are continuing to conduct POD meetings. These meetings include updates on previously identified issues in keeping with the Listen-Act-Develop model of the Physician-Organization Collaboration and the Listen-Sort-Empower model.(7) The success of the POD framework in the pilot departments has stimulated other DWDs to initiate POD meetings within their departments.

The outcomes reported here reflect the experiences of departments already engaged in physician wellness activities. Evaluation of the long-term sustainability and effects of POD meetings on individual physicians, departments, and the overall physician wellness culture will require a formal assessment. Departments without an established program in physician wellness may require additional or alternative approaches to develop a successful POD program.

In addition, as more unique physician input is received, mechanisms for developing and sharing action plans and reporting institutional initiatives that span multiple departments will be needed. The process of ongoing mental health support and bidirectional communication between institutional leadership and physicians will require synergistic communication strategies, such as a user-friendly website and/or apps, town halls, and other periodic wellness messaging.

Operational Implications

There are significant operational implications. Re-establishing community among a cohort of physicians with high levels of burnout, clinical overload, and occupation-related stress is challenging. POD meetings help re-establish a personal connection among physician colleagues in both virtual and in-person formats, though many participants commented that in-person meetings were more impactful in community-building.

Given the enormous budget impact of physician turnover, funding the ongoing administrative structure to support physician wellness is a high-yield investment. Although the DWD role is not required to implement PODs, the formally appointed and funded DWD was a key component to the success of these POD meetings.

The POD communication structure amplifies the unique skills of the DWD in their role as physician leaders who are well-positioned to comment on modifiable professional burdens that detract from professional wellness and fulfillment. The physicians who participated in the POD meetings contributed unique insights to the granular issues that affect the health and wellbeing of the health system and individual physicians. The participating physicians contributed their voices in a grassroots model that is anticipated to enhance professional fulfillment and personal wellbeing through increased professional autonomy and a sense of professional community. The individual perspectives helped create an effective institutional roadmap, guiding the path to a thriving culture of wellness.

The physician leaders also benefited from this cost-effective model of assessment. Findings from POD meetings led to organized, actionable items, directly informed future directions of departmental initiatives, and enhanced communication. Although not every concern was associated with a “quick fix,” communication about both short-term and long-term planning is meaningful to physicians and leaders.

Our findings and lessons learned from the PODs intervention are shared with the intent to inform further work in using enhanced communication techniques to empower physicians in the important area of physician wellness and burnout avoidance.

References

American Medical Association. Measuring and Addressing Physician Burnout. AMA, May 3, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/measuring-and-addressing-physician-burnout .

National Academy of Medicine. National Plan for Health Workforce Well-being. 2022. https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/national-plan-for-health-workforce-well-being .

Hodkinson A, Zhou A, Johnson J, et al. Associations of Physician Burnout with Career Engagement and Quality of Patient Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070442. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-070442

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Nedelec L. Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9385

Sinsky C. What Is Physician Burnout? AMA blog. February 16, 2023. https://ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/what-physician-burnout .

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, West CP. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004