Even with the right training and interest in assessing and treating mental health conditions in primary care, primary care providers (PCPs) often refer patients with these problems outside of the clinic because of the providers’ limited time or other financial or organizational factors. This is why many organizations use the integrated behavioral health (IBH) service specifically to augment what the rest of the medical home team is doing.

Accordingly, your organization’s needs and reasons for integrating IBH likely will drive the model you select. The following sections list important areas of consideration, including your clinic philosophy, patient population, staff members’ needs, and your healthcare goals.

ASSESSING YOUR NEEDS

Mental and physical healthcare historically have been separated from one another. Moreover, unhelpful historic conceptualizations and misunderstandings of mental health and behavioral health may leave some medical practices struggling with how to best “house” behavioral health under one roof. In many cases, the lead PCPs and nurses in the clinic will report that they don’t know how to help the behavioral health professionals (BHPs) get up and running because they are unfamiliar with the needs of these professionals.

This is relevant to assessing your needs, because your BHPs need what your PCPs need, not in terms of equipment, but in terms of leadership support, inclusion in all clinic issues and priorities, and administrative support at the clinical level. Consider treating your BHP as an essential component of the care you provide in primary care, and no different from one of your PCPs.

Below is a preparation checklist. Think of it as a warm-up for your business plan. Initially, consider answering these questions without conducting extensive research on your clinic (e.g., finances, patient population).

Also consider photocopying this list and having your clinical, non-clinical, and management staff complete it as a way to assess their interest in and receptiveness to integration. If they are not receptive or don’t see the relevance, it will be important for you to help them learn why integrated behavioral health services are important to patients and how they will help the team practice more effectively and efficiently attain its goals.

System change is often difficult. Feedback can reveal changes your staff would welcome, which can serve as initial targets for change.

Preparation Checklist

Who would you like to use this service?

What percent of your patient population do you intend to reach with this service?

Are you looking to serve a specific population (e.g., children and adolescents, geriatric patients, patients with substance abuse habits, etc.)?

Are you interested in better disease management specifically for one disorder (e.g., depression, diabetes, chronic pain)?

Is your desire to help as many patients in your population as you can?

What staffing, IT, space, and other resources do you already have to help implement this program?

What financial resources can you identify?

What is your desired timeline for implementation?

What is your desired timeline for gaining a return on investment (ROI)?

What are your related accreditation or other regulatory goals and pressures?

What is the motivation and “buy-in” among your leadership to developing integrated behavioral healthcare?

How high is your clinical staff’s motivation to address mental health needs?

What is your staff’s current understanding of mental health? Mental health covers a wide range of clinical areas, from patient motivation for health behavior change, to health goal setting, mental health treatment, and managing acute and chronic conditions through nonpharmacological means.

What resources do you have to manage this paradigm shift as you launch?

How ready is your staff to tackle new and exciting ways to deliver healthcare?

What are the needs and values of your patients (e.g., low health literacy, expectations for delivery of healthcare)?

What are your clinical staff members’ assets and challenges with regard to delivering care via team-based methods, communication, exploring patients’ values and preferences, and enabling patients to follow through with often-difficult mental and behavioral health changes needed to maintain or improve health?

How are you doing on Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) metrics related to diabetes, depression, and pain care for adults? What about your HEDIS metrics for children and adolescents?

What are your most costly chronic diseases?

How much is patient nonadherence costing you financially? How much damage is it doing in preventing positive health in your patient population? To what extent does it inconvenience your practice?

Is high utilization a problem (e.g., increasing overall cost of care, decreasing clinic efficiency or access)? How does this affect your practice?

How does your staff see behavioral health services being best integrated into what your medical home already offers?

What aspects of your patients’ health would receive more attention if you had an immediately accessible behavioral health resource daily?

PROPOSING THE INITIATIVE TO YOUR PCP STAFF

One way to effectively trigger a revolt among your PCP staff is to mandate practice processes, models, or tools without securing any buy-in from them. Therefore, during these planning stages, consider sampling your PCPs’ attitudes toward the behavioral health issues they face.

First, you should define the important terms for your staff using standard interprofessional language so your polling results accurately reflect commonly defined problems, clinical and workflow expectations, and your PCPs’ beliefs about the prospect of integrating behavioral health.

Most PCPs today have had some training in mental health issues commonly seen in primary care, but their views of the relative importance of these issues versus medical issues and whether they are “their business” can vary markedly.

PCPs’ comfort levels in dealing with patients’ emotional disclosure can also vary. If they are not comfortable handling patient expressions of emotion, do not feel at ease assessing such problems, or don’t know how to assist patients, including how/where/when to refer these patients for additional help, they likely will avoid mental health issues. Some may simply find it easier to avoid opening Pandora’s Box.

Still, there is much evidence that PCPs miss or ignore psychosocial variables patients reveal during medical appointments, much of which are emotional content, body language, or other direct attempts to bring up mental issues during visits.(1-3)

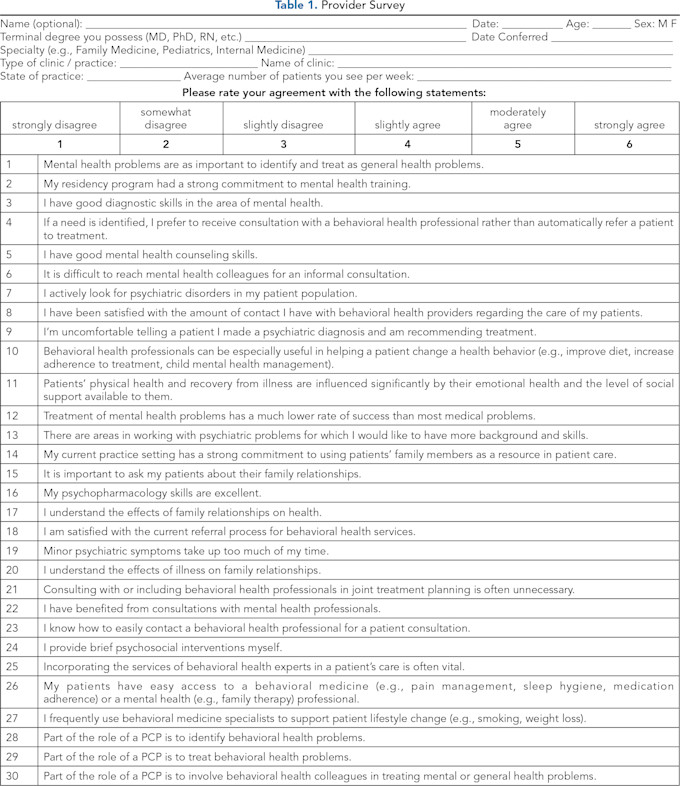

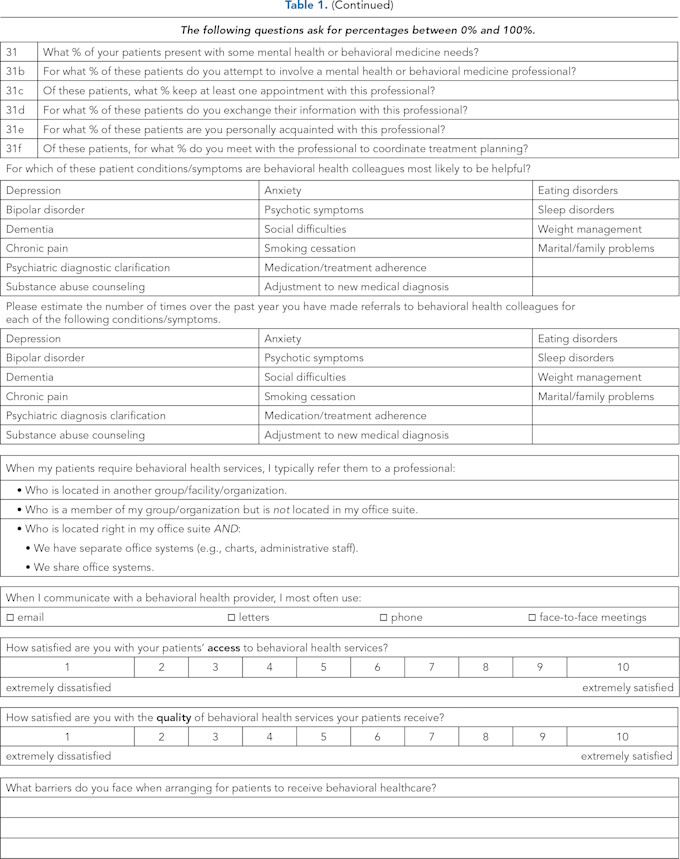

One way to secure early buy-in from these stakeholders is by eliciting their thoughts and opinions through survey questionnaires like the one in Table 1. Collecting this information and providing feedback about the results, including the opportunity to discuss the results, can help steer your organization toward models of integrated behavioral healthcare the PCPs will appreciate and use.

This process can facilitate a common understanding across the medical and business staff (e.g., managers, administrators) that behavioral healthcare issues are indeed important in their own right, that they do affect patients’ overall health, that they are “PCPs’ business,” and that PCPs can learn to handle them more efficiently and effectively with the assistance of IBH services. The survey included in Table 1 may also be used as a pre-post measure to compare scores before and some time after you launch IBH.

Keep in mind that the maturity of your medical home may partially drive your PCPs’ response to this questionnaire. So if your medical home is struggling to conduct huddles, implement team-based care, scrub schedules in advance, use email and phone methods to conduct some care, facilitate all staff to operate at the peak of their relative specialty, optimize access, achieve high customer satisfaction metrics (or even collect them at all), and strive for the Triple Aim, they may be overwhelmed or uninformed about IBH and therefore favor a co-located specialty mental health model in which specialty mental health services are located inside the clinic for their use.

PREPARE, PLAN, PREPARE, PLAN

Preparing before program initiation, securing buy-in from all stakeholders, anticipating obstacles, and developing solutions in advance can help avoid program failures and staff and patient dissatisfaction with your new services. DO NOT simply read the primary literature about integrated care or hire a BHP to do so and then attempt to launch your program. This is like reading your car’s owner’s manual and then attempting to build a similar car by yourself.

In 2014, the RAND Corporation published a report summarizing their study of 56 integrated care programs that were grant-funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

The outcomes were not as impressive as they could have been. The report concluded that not fully developing or implementing a clear model and program (i.e., not implementing a specific, structured, and well-developed model), and low patient program use were among the primary reasons limiting success. Additional publications have argued that these shortcomings need to be improved for future integration programs to maximize success.(4,5)

Consider reviewing the resources posted on the website for the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC). The organization provides information about patient-centered care, optimizing your medical home, behavioral health in pediatrics, and issues related to IBH services. They may be especially helpful for gaining stakeholder buy-in and averting problems associated with clinical staff not being ready or receptive to IBH.

While it is logical for primary care organizations to seek integration through partnerships with local mental health organizations, this venture is exceedingly difficult. At the ground level, most of these mental health professionals will have no experience with integrated care. That’s to say, they commonly operate independently, not as part of a team; with little interest, experience, or knowledge in the medical aspects of patients; and with limited understanding of the primary care culture and the medical home model.

Some would say that historically, specialty mental health providers have conducted care in a way that inadvertently excludes the patient’s primary care team. Also, the majority of mental health providers have little to no training in the highly specific core skills required to deliver IBH models.

Simply contracting services out to a mental health organization carries macro-level problems, too. When mental health and primary care organizations do not share the same operational and financial risks, benefits, and systems of doing business, there is very little integration, clinically or otherwise. This means neither party benefits fully from the advantages integrated care offers.

Research has taught us that partially integrated care, poorly planned integrated care, lack of shared risk-taking by all parties, and poor leadership buy-in hinder the success of integrated care programs.(4,5)

DOING THE PRELIMINARY WORK

In summary, ask yourself and your staff the who, what, where, and why for launching an integrated behavioral healthcare service. This will make it easier for you to find business cases that not only seem reasonable from a financial perspective, but also that will be more easily embraced by your staff and patients. Implementing these programs requires change. This preparatory exercise reveals your paths of least and most resistance, which may draw you toward one model of IBH versus another.

Excerpted from Integrating Behavioral Health into the Medical Home: A Rapid Implementation Guide by Kent A. Corso, PsyD, BCBA-D; Christopher L. Hunter, PhD, ABPP; Owen Dahl, MBA, FACHE, LSSMBB; Gene A. Kallenberg, MD; and Lesley Manson, PsyD.

References

Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the Patient’s Agenda: Have We Improved? JAMA. 1999;281(3):283–287. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.3.283

Carey M, Jones K, Meadows G, Sanson-Fisher R, D’Este C, Inder K, et al. Accuracy of General Practitioner Unassisted Detection of Depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(6):571–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867413520047

Craven MA, Bland R. Depression in Primary Care: Current and Future Challenges. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(8):442–448, https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305800802

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. IHI 90-Day R&D Project Final Summary Report: Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; March 2014. Available at www.ihi.org .

Scharf DM, Eberhart NK, Hackbarth NS, Horvitz-Lennon M, Beckman R, Han B, et al. Evaluation of the SAMHSA Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration (PBHCI) Grant Program: Final Report (Task 13). 2014; Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.