Summary:

This article reveals four lessons, gleaned from interviews with Gehry and his colleagues, for successfully managing big projects.

When the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, opened, in 1997, critics hailed Frank Gehry’s masterpiece as one of the architectural wonders of the past century. The provincial government’s ambitious projections had called for 500,000 people a year to make the trek to Bilbao to visit the museum; in the first three years alone, 4 million came. The term “Bilbao effect” was coined in urban planning and economic development to describe architecture so spectacular it could transform neighborhoods, cities, and regions.

But what’s less well-known is that the Guggenheim Bilbao also set a management standard that very few large projects have attained: It was delivered on time, within just six years, and cost $3 million less than the $100 million budgeted. And it has brought more attention, tourism, and development to Bilbao than the sponsors had hoped for, even in their wildest dreams.

In the quarter-century since the Guggenheim Bilbao, Frank Gehry’s projects have repeatedly come close to or met the same demanding standard. “People presume I’m going to be over budget,” Gehry told us with a little exasperation. “Which isn’t true. All my buildings are built to the budgets agreed upon with the clients.” His record for meeting deadlines and working within budgets isn’t perfect. But it is extraordinary.

Consider the data. One of us (Flyvbjerg) has led a team at Oxford to gather data on the costs and benefits of major projects around the world. The result is a database that includes more than 16,000 projects—everything from large buildings to tunnels, bridges, dams, power stations, mines, rockets, railroads, highways, oil and gas facilities, solar and wind farms, information technology systems, and even the Olympic Games. Collectively, it paints a portrait of big projects across the world. And the portrait is not pretty: Only 8.5% of them were delivered on time and on budget, while a nearly invisible 0.5% of projects were completed on time and on budget and produced the expected benefits. To put that more bluntly, 99.5% of large projects failed to deliver as promised.

In that light, what Frank Gehry accomplished in Bilbao and elsewhere is astonishing. When you also consider that most of the projects in our database are relatively routine, whereas Gehry’s projects invariably do things that have seldom or never been attempted before, his record looks downright miraculous.

The Guggenheim Bilbao set a standard that very few large projects have attained: It was delivered on time, within just six years, and cost $3 million less than the $100 million budgeted.

So how does he succeed where so many others fail? In our interviews with Gehry and his colleagues, and from years studying his work, we’ve observed consistent patterns in the way he manages projects. From these, we have distilled four lessons that may help you make better decisions on the projects you manage.

Make Sure You Have the Power to Deliver What You’re Accountable For

Before he came to prominence, Gehry had lived and worked as an architect for more than 30 years in Los Angeles, designing single-family homes and other modest projects with thin budgets. He had developed a reputation for putting cheap materials—plywood and chain-link fencing—to innovative use. In time, the projects he was offered grew in scale, ambition, and cost.

His big break came in 1988 when he was chosen to design the Walt Disney Concert Hall, a major new cultural addition to Los Angeles, underwritten by a $50 million gift from Lillian Disney, the widow of Walt. It was Gehry’s first world-class commission and a huge step up for the architect, who, despite his experience, had never worked on such a scale.

But some of the powerful executives and city officials who had a hand in the project saw Gehry as an unproven minor-league player. Worse, he was an oddball known for using weird and cheap materials in his buildings. “They were scared to death of Frank,” says Richard Koshalek, chairman of the committee that had awarded the project to Gehry. So they sidelined him, asking him to deliver an initial design but not a detailed, buildable plan. That job would be given to an executive architect, with whom Gehry would share control of the project.

The process Gehry follows from an idea to a finished building is based on trust. Trust produces power—and power gets projects done.

As Gehry puts it, “There’s a tendency to marginalize and treat the creative people [the architects] like women are treated, ‘Sweetie, us big business guys know how to do this, just give us the design, and we’ll take it from there.’ That is the worst thing that can happen.” As Gehry predicted, the division of control on the Disney project didn’t work. The executive architect could not figure out how to turn Gehry’s daring vision of curved, flowing forms into something that could feasibly be built. The project stalled before construction even began. To observers, it seemed that fears about his ability to deliver were justified. Gehry felt like he was shouldering the responsibility—and blame—without having the power to fix things.

The project languished for 10 years, during which Gehry both won and completed the Guggenheim Bilbao project. Then Eli Broad, the billionaire philanthropist, led a push to revive the Los Angeles project but maintained the stipulation that Gehry would provide initial design work only. Gehry responded with a public resignation from the project, and at that point, Diane Disney Miller—daughter of Lillian and Walt—intervened. “We promised Los Angeles a Frank Gehry building, and that’s what we intend to deliver,” she declared. There would be no further funding from the Disney family if Gehry was not kept on as the architect. Broad backed down, and in 1999, more than a decade after he won the commission, Gehry was finally given free rein over the project.

With Gehry at last in control, the project took off and was completed four years later at a cost that met the budget set when he took the helm. Like the Guggenheim, it was dazzling. “Few buildings in the history of Los Angeles have come burdened with greater public expectations than the Walt Disney Concert Hall. None has lived up to such expectations so gracefully,” wrote the Los Angeles Times’ architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff. “It should be ranked among America’s most significant architectural achievements.”

Frank Gehry’s long struggle to create the Walt Disney Concert Hall taught him something fundamental. Control was indispensable. He had to have it, and keep it, from beginning to end. He even coined a term for the setup he needed to be in control—“the organization of the artist”—with the creatives, that is, Gehry and his team, in charge. He has enforced this setup on every project since Disney Hall. It’s a root cause of his success.

The form of his salvation taught him something else as well: If those in positions to grant power trust the project leader, she will have power; if they don’t, she won’t. As we’ll see, the process Gehry follows to take a project from an idea to a finished building has many virtues. But underlying all of them is the fact that his process is based on trust. Trust produces power—and power gets projects done.

Always Ask Why

In 1991, when Gehry was invited to join the project that became the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, regional government officials acting as the client knew what they wanted. In the center of Bilbao, there was a huge old building with impressive towers and arches that had once been a wine warehouse. The officials wanted to transform it into a dramatic space for modern art and have the Guggenheim Foundation run it.

With such a clearly defined project, another architect may have treated this as a simple choice: either accept or pass. Gehry did neither. Instead, he did what he does with every potential client. He asked questions, starting with the most fundamental: “Why are you doing this project?”

What Gehry heard was that Bilbao is the heart of the Basque Country and was once a hub of heavy industry and shipping. But that was in the past. “Bilbao was not quite as bad as Detroit, but almost,” Gehry recalled several years later. “Steel industry gone. Shipping industry gone. It looked pretty sad.” Spain had an enormous tourism industry, but few people had even heard of Bilbao, let alone thought of going there. The officials told Gehry they wanted the museum to do for Bilbao what the Sydney Opera House had done for Sydney—give the city international prominence, draw tourists from around the world, and boost the economy.

That was a lot of weight for any project to carry, and it was hard for Gehry to see how the project envisioned by the officials could deliver what they wanted. Although he liked the building they had selected, it wasn’t well suited to be a space for modern art. And when had a renovation ever had such a transformative effect? But understanding the goal of the project helped Gehry form a different vision that his clients could buy into. Gehry found a derelict site on the riverfront, next to a spectacular bridge, just like the Sydney Opera House. Build something audacious there, he suggested.

Far too many projects proceed on the basis of undiscussed assumptions. That’s dangerous. As the old adage has it: “Don’t assume. Verify.” Gehry does this by asking why. Assumptions may mask disagreements about a project’s ultimate goals. As a result, the initial conception of the project may be off. And without clear agreement on the goal, it will be at greater risk of wandering off course when it encounters inevitable problems and complications. By starting projects with meaningful questioning, and by carefully listening to the answers, Gehry figures out what the clients really want rather than what they think they want. As Meaghan Lloyd, Gehry Partners’ chief of staff, told us: “Sometimes he produces something for the client that they don’t realize they want because [he] listens so well.”

Starting with questions, and really listening, is unnatural. As the Nobel-laureate psychologist Daniel Kahneman has shown, people suffer from availability bias, letting their thinking rush ahead on the basis of whatever information they already happen to have. Gehry’s questions put a stop to that. “You’re being curious,” Gehry says. “And that curiosity leads to invention.”

It’s a skill Gehry developed in the 1960s, when he had marital problems and joined group therapy sessions where he took note as others revealed their inner turmoil. “I was able to dismantle the wall I had built around myself,” he told a biographer. “I began to listen. I don’t think I had ever listened before. But I heard what people were saying, heard it clearly. The more I listened, the more interested I became in them.”

So when real estate developer Bruce Ratner approached Gehry in 2004 to build a 50-story high-rise on a site in lower Manhattan, Gehry asked him why he wanted to do that. What Gehry heard was that the project wasn’t only a business proposition: Ratner wanted to make a prominent addition to the world’s most famous skyline. In that case, Gehry told Ratner, the project needed to be taller. Ratner accepted but then lost his nerve during the 2008 financial crisis, when he wanted to erect a building only half the size. Gehry insisted on the original vision, and when the 76-story building at 8 Spruce Street opened in 2011, it was the tallest residential tower in the Western hemisphere and “the finest skyscraper to rise in New York since Eero Saarinen’s CBS Building went up 46 years ago” according to the New York Times. And it never would have happened if Gehry hadn’t asked “why” and listened to the response.

As open and fluid as Gehry’s process is, it is not formless. Everything from the building’s relationship with its surroundings to the width of a windowsill has been subjected to scrutiny.

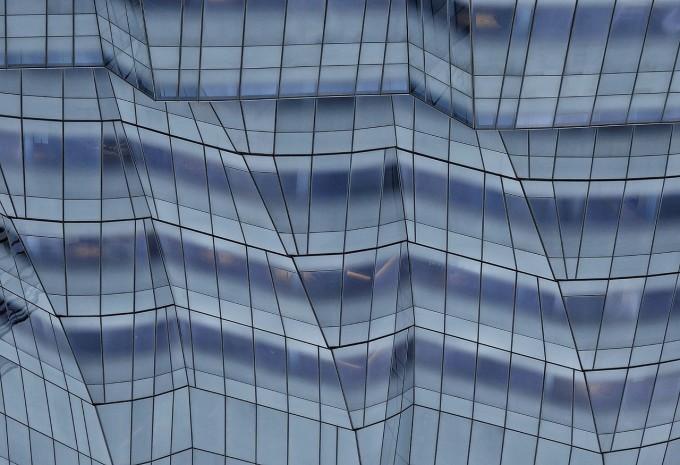

Gehry doesn’t always push for the grand scale. When Luma, an arts foundation based in Arles, France, the city famous for Vincent van Gogh, asked Gehry to design its central building, his vision was down-to-earth and practical: a low, horizontal building that could display artwork of widely disparate types and sizes that would have to be shuttled in and out. But the foundation’s head, Maja Hoffmann, wanted more of a landmark: a “lighthouse” tower that could be seen far and wide. Together, the two developed a synthesis—a low, circular, glass base topped with a stunning, multifaceted stainless-steel tower that sparkles with reflected light. The result is both practical and beautiful. It’s also a testament to the power of collaboration.

Simulate, Iterate, Test

When prospective clients come to Gehry’s firm, they are walked through the development of past projects so that they understand Gehry’s process. That’s crucial because the discussion to shape the project’s initial conception is not the end of their involvement. It’s the beginning. “Some people aren’t up for it,” notes Lloyd. “It takes a brave person to work with us.”

In designing Ratner’s Manhattan skyscraper, for example, Gehry started by “playing”—his description—with ideas in various media: doodles on paper, crude models with paper and wood, images on a computer. Initially, he imagined a twisting tower, like a long piece of licorice, and he played with many variations of that. But he worried that it wouldn’t give people the feeling of solidity that they needed to live comfortably in a Manhattan skyscraper not many years after the 9/11 attack. So he moved on to other ideas, trying one, then another, and another.

At last, he hit on the idea of a rectangular tower with a facade made of stainless steel and glass that would bulge and recede in order to create the illusion, at a distance, of cloth rippling in the wind. Many more iterations followed. Finally, they decided they had what they wanted. It was the 74th iteration.

In doing this work, Gehry collaborates with others to create models and digital simulations, and he constantly asks for candid judgments. This is not pro forma consultation. Gehry gives feedback serious consideration and adjusts his work accordingly. Then he seeks further feedback.

It helps that Gehry seldom, if ever, speaks in high-flown theoretical terms, despite having studied art and architecture deeply. He is blunt. He expects the same in return. “Our communication is very basic and mostly visual, and there’s not a sophisticated language that we use,” says Craig Webb, a partner in Gehry’s firm. They look at models and say, “That’s good” or “That’s bad” or “I don’t like it.” Ideas that work are kept; those that don’t, go. The work takes priority over any bruised feelings.

But it’s one thing to imagine, sketch, and model a skyscraper whose facade looks like billowing cloth. It’s quite another to design one that can be built. For the 8 Spruce Street project, there was a major additional constraint: The client had stipulated that the total cost had to be roughly comparable to a standard skyscraper.

Gehry’s team spent two years thinking through and simulating every detail, in effect building the museum on computers before they built it in reality.

Solving this puzzle would have been impossible without CATIA, a computer-modeling technology modified from software originally created to design aircraft by the French aerospace giant Dassault. Gehry recognized long before most that if computer modeling were pushed to extremes, it could revolutionize design and construction by allowing architects to engage in relentless iteration and testing of every imaginable form, including curves that had once been impossible to build reliably.

The result would be digital models that precisely mimicked the future building, providing exquisitely detailed plans that could be used by everyone from manufacturers to builders to operators. Starting with the Golden Fish sculpture designed for the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, digital models have been key to all of Gehry’s designs, long before anyone came up with the term “digital twin.”

Central to Gehry’s vision for 8 Spruce Street was its billowing facade. To design it, Gehry and his team modeled it piece by piece, painstakingly examining the implications of every design choice for the exterior facade, the interior apartments, and the cost of manufacturing and installation. The steel manufacturer took the resulting plan and produced the pieces, which were brought to the construction site and assembled like an immense, vertical jigsaw puzzle.

“If you were to do this [design work] by hand, you might get two or three tries within the allowable design period,” notes Tensho Takemori, an architect at Gehry’s firm. But thanks to digital simulation, “we had thousands….And because of that, we were…able to reduce the cost to almost the same as a flat curtain wall. The proof is there were no change orders, and that’s a pretty unheard-of result for a 76-story tower.”

As open and fluid as Gehry’s process is, it is not formless. At various points, decisions are locked in. Work then proceeds on the next stages. The overall effect is to move smoothly from big ideas at the grand scale (What about a skyscraper twisted like licorice?) to increasingly fine-grained details (How do we design this window?). As a result, everything from the building’s relationship with its surroundings to the width of a windowsill has been subjected to severe scrutiny. It’s a long, exhausting process, but the resulting plan isn’t only unusually detailed. It is unusually reliable.

The client is involved throughout. “It’s a discussion,” Gehry says. “That’s why the model-making thing is great, because they can see it as we develop it, and understand what I’m agonizing about.” Gehry is seldom perfectly happy with anything. “I’m very open about that,” he says, and he frankly shares what he likes and what he doesn’t. He wants the same candor from the client, and when he gets it, he listens intently and synthesizes the client’s thinking into his own. “They see they’re involved,” Gehry says. “They’re invited into my thinking process. So they can see stuff. And they can say, ‘Oh no, I would never do that.’ They can feel like part of it. They see the evolution. I find that very powerful.”

At key stages, when the project must commit to design decisions before work advances, the client must give approval. In this way, the design is enriched and strengthened by the client’s perspective, while the meeting of minds that begins the project continues, iteration after iteration, following the maxim, “Try, learn, again.”

Think Slow, Act Fast

Gehry’s process asks much of everyone involved. It also consumes a great deal of time. For project proponents eager to have something to show for their efforts—and get to the finish line—extended planning can be frustrating, even unnerving. For them, planning is pushing paper, something to get over with. Only digging and building are progress. If you want to get things done, they think, get going.

This sentiment is easy to understand. But it is wrong. When projects are launched without detailed and rigorous plans, issues are left unresolved that will resurface during delivery, causing delays, cost overruns, and breakdowns. A scramble for more time and more money follows, along with efforts to manage the inevitable bad press. With leaders distracted in this manner, the probability of further breakdowns—more scrambling, more delays, more cost overruns—grows. Eventually, a project that started at a sprint becomes a long slog through quicksand.

A dramatic example of this dynamic is the tragic story of the Sydney Opera House and the young genius who designed it. Like Frank Gehry, Jørn Utzon was an architect of rare vision. To win the competition to design the project, he had submitted an entry that was little more than a few sketches—the art critic Robert Hughes called them “a magnificent doodle.” But because of political pressure to complete the project, construction began before Utzon could figure out exactly how to deliver on his sketches. Costs rose rapidly from the get-go. Completed work even had to be dynamited and cleared away to start again. In 1966, Utzon was pushed out and replaced, with his famous roof shells barely erected and no interior work done. When the Opera House finally opened, in 1973, it was acoustically unsuited for opera and flawed in many other ways. Scheduled at five years, the project had taken 14. The final bill was 15 times the budgeted amount, one of the biggest overruns in history.

By contrast, the Guggenheim Bilbao, a building no less innovative and complex than the Sydney Opera House, took four years to build—exactly as forecast—because Gehry and his team had spent two years up front thinking through and simulating every detail, in effect building the museum on computers before they built it in reality.

Gehry’s planning process may burn considerable time and feel slow, but overall his approach is much faster. And cheaper, because planning and delivery costs are wildly asymmetric: Spotting and correcting problems with the 8 Spruce Street facade by making thousands of iterations on a computer may not have been cheap in an absolute sense, but it cost a small fraction of what it would have to fix the same problems had they been discovered during installation. Relatively speaking, planning is cheap, delivery is expensive. And taking the time to think through the design means you can act much faster later.

. . .

Rules like those we describe here attempt to convey meaning that can never be entirely put into words. Gehry’s modest early projects and experiments with materials are worlds away from his masterpieces of modern architecture, yet, in a fundamental sense, he built the latter on the tacit knowledge garnered from building the former. Those who lack experience with following rules of this kind must keep that limitation in mind. The rules indicate directions of travel, but they are not road maps. To bring them fully to life, and to make decisions as adeptly as true experts like Frank Gehry, you must cultivate the underlying tacit knowledge the way Gehry did: by doing.

Editor’s note: Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner are the coauthors of How Big Things Get Done (Random House, 2023), from which this article was adapted.

Copyright 2023 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate.

Topics

Strategic Perspective

Environmental Influences

Action Orientation

Related

The Founder and CEO of Prologis on Staying Ahead of Disruptive ChangeWhat, Exactly, Is a CMO?How to Make a Seemingly Impossible Leadership DecisionRecommended Reading

Problem Solving

What, Exactly, Is a CMO?

Problem Solving

How to Make a Seemingly Impossible Leadership Decision

Strategy and Innovation

Leonardo, Dragonflies, and Observation

Strategy and Innovation

What to Do When Your Senior Role Feels Totally Unsustainable

Strategy and Innovation

How to Stand Out to C-Suite Recruiters