Abstract:

The study compared the use of a discharge readiness tool (DRT) along with an interdisciplinary rounding model on selected operational outcomes and healthcare team satisfaction. The DRT resides outside the patient chart but within the EMR, providing a quick visual of progress toward discharge readiness. Twice-daily medical team huddles identified patients closest to discharge and addressed barriers. Data collected pre/post intervention included length of stay (LOS), discharge time, team satisfaction, and patient satisfaction. The intervention unit’s LOS decreased by 0.26 days during the study period compared to the control unit. Effective discharge time (order placed to discharge) was 21 minutes faster in the intervention unit. There was no change in patient satisfaction, however team satisfaction improved.

One of the challenges in acute care settings is expediting discharges to accommodate admissions for planned procedures as well as admissions from the emergency department (ED). Failure to maintain efficient throughput can create a backlog in the ED(1) and tie up physicians and nurses in time-consuming triage. Electronic medical records (EMRs) have been adopted as the documentation vehicle throughout acute care settings. Leveraging the collected data to improve both effectiveness and efficiency in provision of care, including the discharge process, is an area for current and future exploration.

Use of interdisciplinary rounding models has been found to improve discharge processes and team satisfaction,(2,3) but it still can be time-consuming when review of all patients is completed. Combining the use of a new rounding model and discharge tool derived from the medical record provided an opportunity to study the impact on discharge processes and outcomes.

Background and Significance

Initial uses of the data collected in the EMR have been to compare outcomes, identify trends, compare processes between identified entities,(4,5) and improve safety.(6,7) For example, Grion, et al., developed a computerized tool to decrease potentially inappropriate medication in geriatric patients.(6) Walraven and colleagues developed a tool, LACE, to predict readmission and early death after discharge from hospital to community.(5) Issues with the LACE tool related to manual entry led to limitations of use.(5) Early warning systems to identify signs of early deterioration based on mining of physiologic data from the EMR have been developed.(9-12) Implementation of real-time warnings via notification within the EMR to alert the healthcare team has been reported with associated positive results in decreasing the activation of rapid response teams. Implementation of real-time tools for discharge readiness was not found in the literature.

This article provides results of a pilot study comparing the use of a discharge readiness tool combined with an interdisciplinary rounding model on selected operational outcomes and healthcare team satisfaction. The innovative development and use of the discharge tool using data from the EMR addresses an improvement in the discharge process and triage of patients for discharge, ultimately improving throughput efficiency.

Development of the Discharge Readiness Tool (DRT)

As part of his role, the physician advisor assists hospital leadership and medical staff to ensure appropriate utilization of healthcare resources. Working closely with case managers, the physician advisor provides education for medical staff on the process of patient throughput, medical record documentation, and guidelines addressing medical necessity, level of care, length of stay, and readmissions.

The physician advisor (board-certified practitioner, liaison between hospital administration, clinical staff, and support personnel), manager of care coordination, executive directors of nursing, and a senior information technology analyst designed and built the DRT based on a need to improve patient throughput in a more coordinated fashion.

The DRT, which resides outside the patient chart but within the EMR, was released for use by care coordinators and nursing in May 2015. The impetus for this study was to evaluate use of the tool by the entire healthcare team to promote collaboration, communication, and coordination of care within the team and to improve the discharge process.

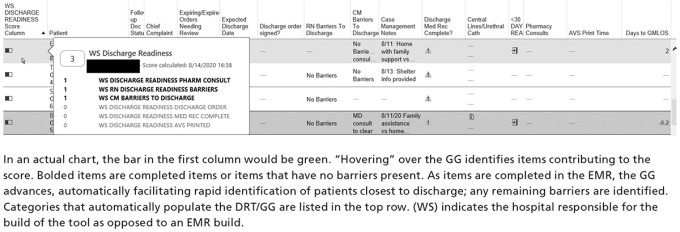

A key feature of this tool is that it provides real-time information for the patient, including barriers to discharge, a rolling length of stay (LOS) based on admission diagnosis, and a discharge indicator (DI) displayed as a green gauge (GG), indicating completion of needed elements for discharge (see Figure 1). The rolling LOS is a feature of the DRT showing in real time a countdown of hospitalization days to the geometric length of stay (GMLOS) which is depicted in black under the Days to GMLOS column (see Figure 1). A red number indicates hospitalization days beyond the GMLOS. This feature serves as a reminder to the medical team to provide appropriate documentation for an extended hospitalization and confirm medical necessity.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the discharge readiness tool (DRT) with green gauge (GG)

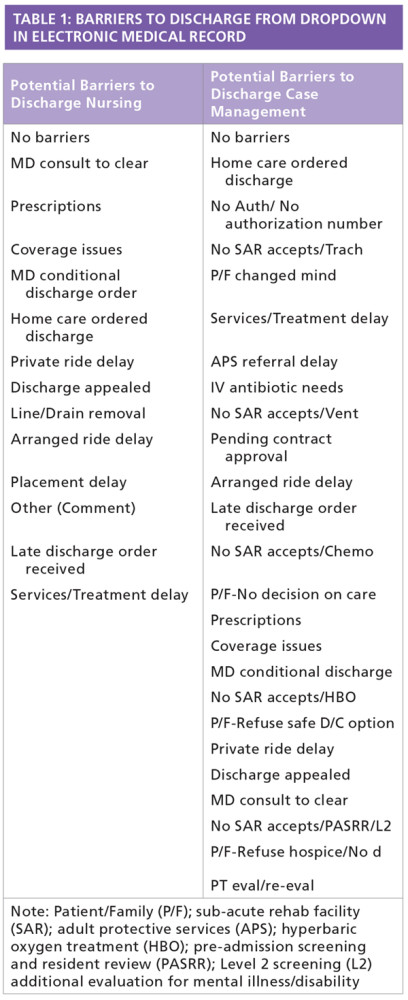

Data are pulled from the EMR based on expected routine documentation that is part of expected practice. Barriers to discharge that make up the elements from nursing and case management that may be present are listed in Table 1 and appear in the designated column of the DRT (see Figure 1). Based on a six-point scale, the DRT provides a quick method to prioritize patients by degree of readiness for discharge, identifying the patients to target for discharge when immediate triage for beds is needed, as well as providing focus for discharge planning for those patients with a longer LOS compared to expected Medicare LOS.

Study Design

The study design compared one medical unit that used the DRT with a specific rounding model to a similar medical unit that used a once-daily standard rounding routine absent the DRT. Twenty-five subjects participated in the staff satisfaction component of the study.

The data collection site included a medical-surgical floor of a teaching hospital before and after the implementation of the DRT, adding physicians as users of the tool, along with a specific rounding model. Data were collected from the targeted medical-surgical floor (intervention unit) for 30 days (September 1–September 30) before and 60 days (October 16–December 14) after implementation. Data also were collected from a medical-surgical floor (control unit) with a similar patient population, bed size, case mix index, LOS, and scores from the most recent standardized measures of the work environment in order to control for extraneous factors within the hospital environment.

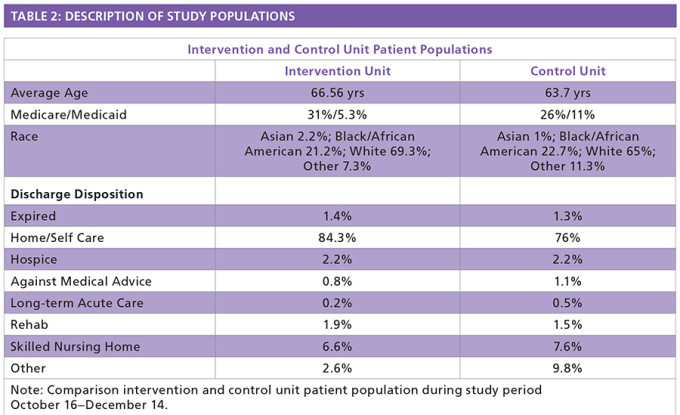

Table 2 provides an overview of patient populations of the two units during the study period. Hospital metrics that were primary outcomes of the study included LOS, number of discharges by the hospital targeted discharge time of 11 a.m., and healthcare team and patient satisfaction scores.

An investigator-created survey was used to measure satisfaction with the discharge process before and after implementation of the DRT. Demographic data (physician, nurse, and care coordinator) of participants was collected as part of the survey. The intervention and control units were comprised of a healthcare team of physicians including medical residents who were supervised by a board-certified internist, charge nurse, and care coordinator.

The intervention unit healthcare team met twice daily, at 8:30 a.m. and at 3:30 p.m., using the DRT to identify patients who were closest to discharge and to address unresolved barriers. The healthcare team was able to prioritize those patients and develop plans to address each barrier. In the control unit, the healthcare team carried out a conventional rounding model (once daily), which did not include the use of the DRT.

The DRT-GG provided real-time scoring of each patient’s readiness for discharge, supporting a quick view for patient focus. Scoring can go up or down based on the number of barriers (see Table 2) to be resolved. The GG increases as each of the following tasks are completed: care coordination and nursing column confirms no barriers; there is no active order for a pharmacy medication review; the provider has completed the medication reconciliation process for discharge; the discharge order is signed; and the after-visit summary (AVS) is printed (see Figure 1).

Points can be accumulated in any order, although the AVS cannot be printed until discharge medication reconciliation is complete. The DRT-GG provides a visual tool with the ability to sort the gauges, bringing the higher scores to the top and allowing the healthcare team to quickly identify those patients closest to discharge. Placing a cursor over the DRT-GG results in a display of a numeric score for the indicated patient (see Figure 1).

Results

Healthcare Team and Patient Satisfaction

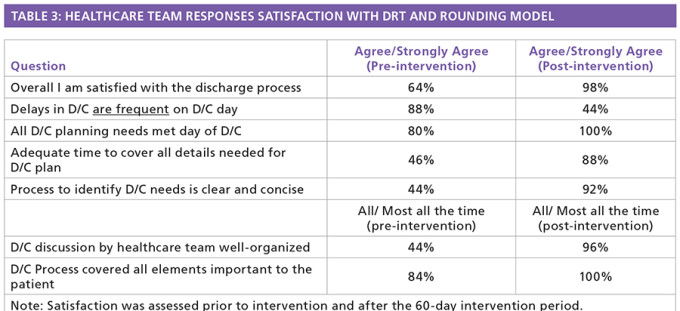

Evaluation of the survey responses of the study group indicated that overall satisfaction with the discharge process improved from 64 percent (Strongly Agree and Agree) to 98 percent. Other measures of efficiency demonstrated improvement following the trial of the new rounding process using the DRT-GG (see Table 3). No statistically significant difference in patient satisfaction was noted on the HCAHPS satisfaction survey comparing pre/post-intervention time frames.

Comparison of LOS and Discharge Times

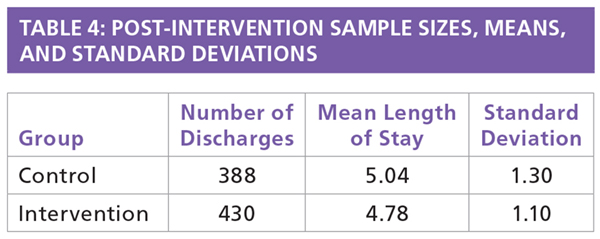

Findings from the study revealed that patient LOS decreased by a little more than a quarter of a day (0.26) in the intervention group compared to the control group. It was also noted that the CMI was similar at baseline for both (control unit 1.34, intervention unit 1.35) and remained similar during the study for both units at 1.36. Number of admissions during the study period (October 16–December 14) were similar: control unit n = 535, intervention unit n = 552.

The comparison of pre-study mean patient LOS indicated no statistically significant difference between the mean patient LOS for the control group and that of the intervention group for the month before the study began (t = 1.11, df = 210, p = 0.268). There was a statistically significant lower patient mean LOS in the intervention group (t = 3.04, df = 760, p = 0.003) with a 95 percent CI (0.09, 0.43) compared to the control group for the 60-day intervention period (see Table 4).

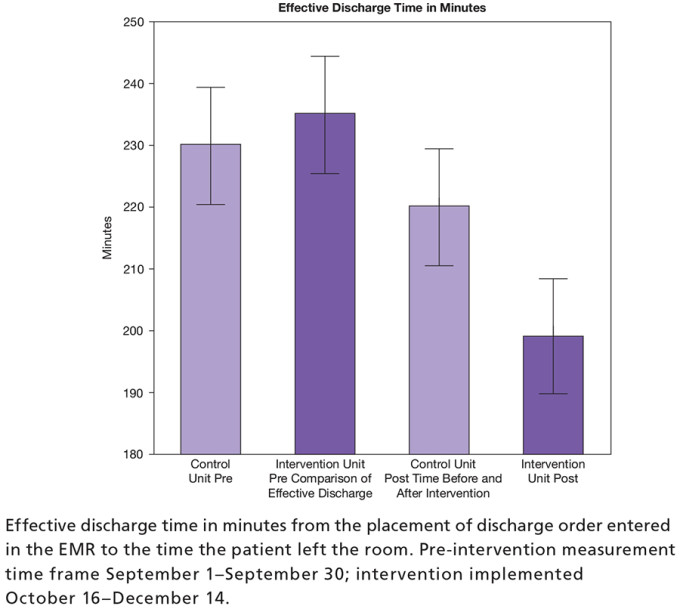

There was a statistically significant difference (21 minutes) in the mean effective discharge time for the intervention group (t = 2.24, df = 735, p = 0.025) with a 95 percent CI (2.89, 39.78) compared to the control group during the intervention time period (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effective discharge time in minutes

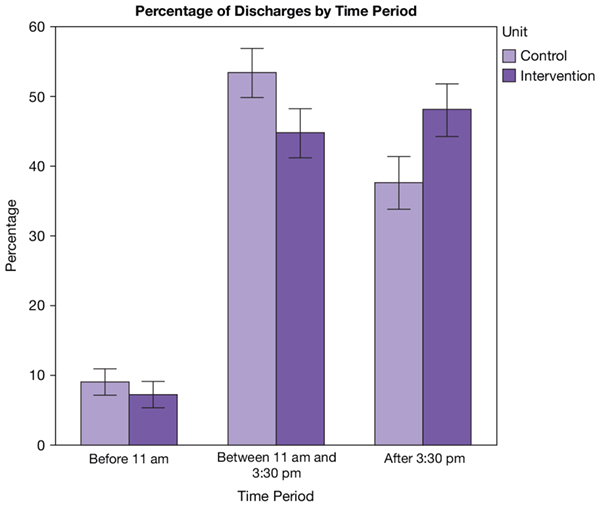

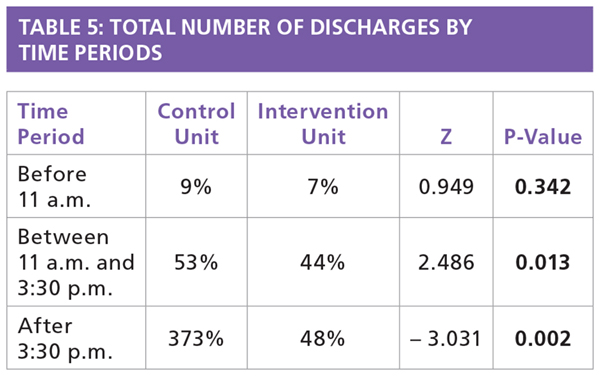

Finally, the discharge time of day was compared between the study and control groups. The percentages of discharges were compared for the time periods “Before 11 a.m.,” “Between 11 a.m. and 3:30 p.m.,” and “After 3:30 p.m.” (see Figure 3). The intervention unit demonstrated an increasing number of discharges throughout the day while the control unit decreased discharges after 3:30 p.m., with a significant difference in percentage after 3:30 p.m. in the intervention unit (see Table 5).

Figure 3. Percentage of discharges per time period

Discussion

This study tested the effect of the discharge readiness tool (DRT) that facilitated a specific rounding model on selected outcomes affected by the discharge process. These outcomes included patient LOS, patient effective discharge time, healthcare team satisfaction with the DRT and rounding model, and patient satisfaction, i.e., HCAHPS.

Analysis of the data regarding discharge time revealed some interesting and useful results. It was noted that more patients were discharged before 11 a.m. in the control group compared to the intervention group. However, the intervention group discharged more patients overall and more after the 3:30 p.m. huddle compared to the control group.

These data identified a tendency in the intervention group for discharging patients throughout the course of the day, which may explain at least in part why the study group had a shorter LOS. These results also suggest that having a specific targeted discharge time may not be important to the discharge process and in fact may delay discharges if incentives are in place for meeting a specific discharge time.

The DRT helped ensure patients were discharged as soon as they were medically ready. In addition, the tool provided a feature (rolling length of stay) alerting the care team of a need to document medical necessity for additional hospitalization days. Overall, the intervention unit discharged more patients (n = 430) than the control unit (n = 388) during the 60-day intervention time frame.

It also was observed that the effective discharge time (time from discharge order entered in the EMR to when patient left the room) was 21 minutes less in the intervention group compared to the control group. Anecdotally, it was noted that the effective discharge time in the intervention group post-implementation DRT compared to pre-implementation baseline was 36 minutes faster. We believe that this result reflects the focus of the intervention group to identify and resolve the barriers to discharge that typically cause delays.

Outcomes from this study strongly support that the implementation of the DRT combined with the rounding model had a significant impact on patient throughput and the patient discharge process. It was observed that the efficient, innovative process using the DRT encouraged and facilitated healthcare team communication and collaboration throughout the workday and improved team satisfaction.

This new approach contributed to an overall decrease in LOS by continuing to focus on discharge throughout the day. Improved coordination of care among the participants in the intervention group contributed to the improved outcomes. Twice-daily huddles performed in the intervention group kept the healthcare team constantly focused on developing discharge plans throughout the day for those patients deemed closest to discharge. Use of the GG within the DRT provided a quick method of identifying the patients to target for discharge.

Anecdotally, nurses and care coordinators indicated that they felt empowered and an important part of the healthcare team to the discharge process. They noted that their input during the team huddles played a significant role in discharging patients in a timely fashion. Physicians reported a better line of communication with other members of the healthcare team. All participants in the intervention group noted that after each huddle they received fewer calls and pages among themselves. Participants indicated that they liked the design of the process with a morning huddle at 8:30 a.m. and afternoon huddle at 3:30 p.m., each lasting 7–10 minutes, which allowed for a quick touch base among team members to maintain a focus on patients closest to discharge.

Since the DRT resides outside the chart, no patient chart was required for the huddles, thus expediting the process. Key elements and information of the patient’s chart are pulled into the DRT, supporting better efficiency of the huddles and discharge process. Team members in the intervention group found the discharge process more efficient and less time-consuming compared to the traditional rounding method and noted a clearer delineation of responsibilities of each participant in the discharge process.

One limitation that should be noted is the setting: a teaching hospital in the southeast. Results may differ in a community hospital setting.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that a discharge readiness tool combined with a specific rounding model of the healthcare team can improve patient throughput and the overall discharge process. The study confirmed that the DRT-facilitated rounding model encouraged and supported better overall teamwork and improved team member communication and collaboration. Use of the DRT supported a more efficient and organized discharge process, which created a more structured approach to patient throughput.

Currently, the process is being disseminated throughout the hospital with plans to implement throughout the 11-hospital system. Future consideration for use of this tool and model could include other care team members such as pharmacists, physical therapists, and other consultants involved in the care of the patient.

References

Mustafa F, Gilligan P, Bue E, et al. ‘Delayed Discharges and Boarders’: A 2-year Study of the Relationship Between Patients Experiencing Delayed Discharges from an Acute Hospital and Boarding of Admitted Patients in a Crowded ED. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(9):636–40.

Pronovost P, Berenholtz, S, Dorman, T, et al. Improving Communication in the ICU Using Daily Goals. J Crit Care. 2003;18(2):71–5

Artenstein AW, Higgins, TL, Seiler, A, Meyer D, et al. Promoting High Value Inpatient Care via a Coaching Model of Structured, Interdisciplinary Team Rounds. Brit J Hosp Med. 2015;76(1): 41–5.

3M Health Information Systems. 3M Solutions for Potentially Preventable Events. 3M Website https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/855236O/3m-ppe-solutions-fact-sheet .

Morr CE, Victor-Seungree N, Woollard S, et al. Analyzing Readmissions Patterns: Assessment of the LACE Tool Impact. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, Schreier G, Ammenwerth E, Horbst A, and Hayn D, eds. Clifton, VA: IOS Press. 2016;25–30. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-645-3-25.

Grion AM, Gallo U, Tinjala DD, Daragjati J, et al. A New Computer-Based Tool to Reduce Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions in Hospitalized Geriatric Patients. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(4):267–75.

Radley DC, Wasserman MR, Olsho LE, Shoemaker SJ, et al. Reduction in Medication Errors in Hospitals Due to Adoption of Computerized Provider Order Entry Systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(3):470–6.doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001241.

van Walraven C, Dhalla, IA, Bell C, Etchells E, et al. Derivation and Validation of an Index to Predict Early Death or Unplanned Readmission After Discharge from Hospital to the Community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–7.

Kipnis P, Turk BJ, Wulf DA, LaGuardia JC, et al. Development and Validation of an Electronic Medical Record-Based Alert Score for Detection of Inpatient Deterioration Outside the ICU J Biomed Inform. 2016;64:10–19. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2016.09.013.

Hackmann G, Chen M, Chipara O, Chenyang L, et al. Toward a Two-Tier Clinical Warning System for Hospitalized Patients. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:511–19.

Rothman MJ, Tepas JJ, Nowalk AJ, Levin JE, et al. Development and Validation of a Continuously Age-adjusted Measure of Patient Condition for Hospitalized Children Using the Electronic Medical Record. J Biomed Inform. 2017;66:180–93. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2016.12.013.

Parrish WM, Hravnak M, Dudjak L, Guttendorf, J. Impact of a Modified Early Warning Score on Rapid Response and Cardiopulmonary Arrest Calls in Telemetry and Medical-Surgical Units. Medsurg Nurs 2017;26(1):15-19.

Topics

Technology Integration

Systems Awareness

Performance

Related

Manage Your AI Investments Like a PortfolioWhy Training Employees Pays Off TwiceDeveloping a Thicker Skin as a Leader