Abstract:

Comprehensive, detailed documentation in the medical record is critical to patient care and to a physician when allegations of negligence arise. Physicians, therefore, would be prudent to have a clear understanding of this documentation. It is important to understand who is responsible for documentation, what is important to document, when to document, and how to document. Additionally, it should be understood who owns the medical record, the significance of the transition to the electronic medical record, problems and pitfalls when using the electronic medical record, and how the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act affects healthcare providers and health information technology.

“Medicine is the only world-wide profession, following everywhere the same methods, actuated by the same ambitions, and pursuing the same ends.”—Sir William Osler

Recent attempts to improve patient healthcare include scientific breakthroughs, medical innovations, and technological advances. Medical records occupy the last category; they are a portal through which all medical staff can investigate the history of the patient to learn about prior medical care, understand the established diagnoses and response to outlined treatments, and synthesize this information in preparation for further evaluation and treatment approaches.

A well-documented medical record serves two worthwhile purposes: (1) it reflects the patient’s history and corresponding medical care, thereby allowing for continuity of care; and (2) it can provide a defense for a physician facing allegations of malpractice by detailing adherence to the standard of care.

Current technologies are bringing medical records into the 21st century through innovative software and hardware computer programs. As healthcare professionals, we must understand that despite the changing platform via which we interact with the medical record, the basics of the medical record remain the same, as does its purpose: to provide information that allows for optimal patient care.

This article reviews who is responsible for documentation, what is important to document, when to document, how to document, who owns the medical record, the transition to electronic medical records, problems and pitfalls when using the medical record (EMRs), and how the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act affects healthcare providers and health information technology.

Documentation

Who is responsible for comprehensive documentation? Succinctly stated, everyone who provides care to a patient is responsible for documenting the care and recommendations that have been provided and articulated to the patient. Medical records are legal documents that are used to demonstrate the thought process leading to the diagnosis and treatment options. All patient encounters should be documented, whether the encounter is in person, over the telephone, or by electronic communication. The documentation should be created contemporaneous with the discussion.

Documentation can be delegated to an assigned recorder during an emergency situation such as cardiac resuscitation. The delegated documentation should be carefully reviewed for accuracy immediately after the event, while the details of the resuscitation are fresh. This is important because even if good care was provided, incomplete documentation can give the opposite impression. The paper medical record recommendations also apply to the EMR, which has been adopted by healthcare entities across the country.(1)

What to Document and Why

Clinical notes should be well thought out, be clearly written, and give a detailed picture of the clinical situation. They must include important information including the patient’s name, age, and gender; the source of the information; and the date and time of the encounter. Additionally, relevant history and details of the physical examination with pertinent positive and negative findings should be clearly stated in the medical record. The conclusions should include a working differential diagnosis and working plan of action, including investigations, consultations, treatment, follow-up, and rationale for the workup and treatment. It is important to document all information shared with the patient, both written and verbal, and to define the patient’s understanding of the plan of action and any refusal or disagreement. The medical note should be signed by the provider.(2)

Good clinical practice and informed consent are inseparable. Respect for patient autonomy in clinical practice is of great moral significance in our society. The moral and legal responsibility of obtaining medical informed consent depends on transmission of appropriate information to the patient. We believe patients’ choices must be made independently and based on the full spectrum of medical knowledge, and not coerced by members of the healthcare team or by third parties, such as family, friends, or payers. Equally, we believe patients must be competent to consent: they must understand, remember, consider, and believe the clinical information given to them about the specific and alternative treatments. The moral foundation for the requirement of medical informed consent in general is not disputed. The medical record must stand on its face to document the clinical, moral, and legal responsibility of the physician to provide the patient with the information to make an informed decision. It is the fiduciary responsibility of the physician to meet this standard.

Physicians and all healthcare providers must recognize that informed medical choice is an educational process and has the potential to affect the healthcare provider–patient alliance to their mutual benefit. Healthcare providers must give patients equity in the covenant of informed choice by educating them to make informed choices. This type of healthcare team–patient relationship becomes a true partnership with shared decision-making responsibility for treatment approaches and outcomes. The medical record must reflect this informed decision-making between the healthcare provider and the patient.(3)

Special Situations

When transferring the care of patients for the evening, the weekend, before a vacation, or for any other reason, we must remember that the individual assuming the responsibility for the patients’ ongoing medical care does not have the same depth of understanding about their medical conditions as the healthcare provider who is handing off the patients. The handoff should document, verbally and in the medical record, the expectations regarding the patients’ condition, the ongoing care required, any pending investigations, any pending consults or reports, any unsolved medical or social issues, and what is anticipated for long-term care. The record should clearly document who is assuming responsibility for medical care, including start and end times with specific dates.

Discharge Summaries

At the time of discharge, it is paramount to document the detailed hospital course, including treatments, complications, and intercurrent illnesses. Clearly document what people were consulted, their recommendations, and all actions taken in response to those recommendations. Identify all investigations and actions taken. Identify pending investigations and who is responsible for following these results. All follow-up actions should document what was done, by whom, and when.

When to Document?

It is best to document contemporaneous with the events, because memory about details fades with time, other events may occur, and there may later be disputes concerning their sequence.

Case Study: Delay in Documentation

A patient is discharged from the hospital, and the discharge summary has not been completed before the patient is readmitted under the same physician. The patient’s second admission is complicated, with prolonged hospitalization ending in death. When the physician completes the discharge summaries for both events, laboratory finding for the second admission are inadvertently included in the first discharge summary. How might this discharge summary compromise the physician? At a subsequent mortality review, there is an inference of a delay in responding to these lab results, with delayed diagnosis and treatment resulting in the adverse outcome of death. Only after detailed review of both admissions was the true sequence of events established and the inference of malpractice negated.

The lesson learned is that a delay in documentation can result in uncertainty regarding the sequence and timing of actions. This can have negative consequences for healthcare providers in terms of reputation and potential for litigation.

Electronic Medical Records

The EMR is here to stay. Healthcare providers must take the time to learn how to use the software and give the same attention to documenting patient care in the EMR as when using a paper record. A significant disadvantage arises because of the length of the EMR, which can make it difficult and time consuming for healthcare providers to find the signals among the noise. A major advantage of the EMR is that it includes tools to help with decision-making and to alert the user to potential problems (e.g., drug interactions). When using such tools, it is vital to write a clear note in the record that documents the thought process that led to the chosen treatment options. The EMR must identify a true partnership between patient and provider, with shared, informed decision-making responsibility for treatment approaches and outcomes.

Informal interactions can become a healthcare provider’s nightmare.

Remember that patients have a legal right to see the content of their own medical record at any time and for any reason, although the physical record belongs to the person or organization responsible for its creation, which is the physician’s office or the healthcare corporation or hospital. The owner of the physical record is responsible for controlling access by others in accordance with privacy law.(4)

Problems and Pitfalls

Informal interactions can become a healthcare provider’s nightmare. Information given or received by telephone without documentation often is forgotten, but can be vital to patient care and prevention of allegations of negligence. Informal discussion in the hallway or supermarket may lead to decisions to do or not do something. If there is an adverse outcome, the reasoning and lack of documentation will be missing.

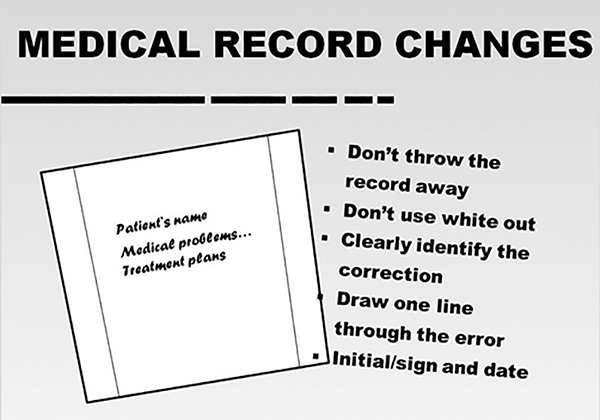

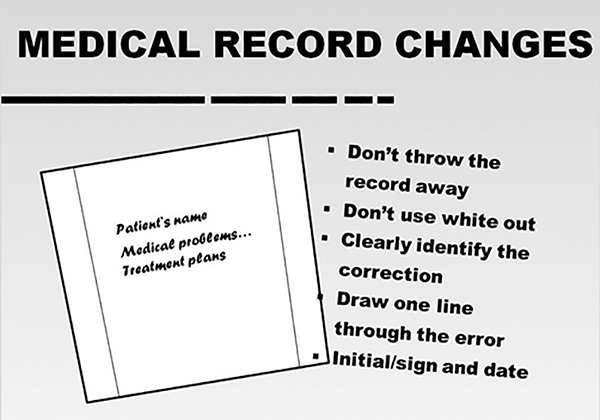

It is important to correct the medical record with precision. In the EMR is it important to indicate the reason for the change and carefully enter the correct information. An EMR should have an audit function that will indicate who made any entries or changes and when these changes occurred—both date and time. If an EMR allows deletion, it should store and permit access to deleted text. The golden rules of correcting the medical record are as follows:

Never allow others to use your password.

Never use someone else’s password.

Never make changes after a patient complaint, or after learning of a legal action (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Guidelines for making changes to the medical record.

A common cause for legal action is improper handling of lab results or diagnostic tests: for example, a test wasn’t performed, the results weren’t reported, the information was sent to the wrong location, the diagnostic test wasn’t interpreted, results were filed before they could be reviewed, or information was not acted upon. Healthcare teams must have a fail-safe system to track, file, and document the results of these tests and how they acted upon the results.(5)

Case: A Case of True Syncope

An emergency department physician (EDP) diagnosed a concussion in a 14-year-old female basketball player who struck her head after experiencing true syncope while playing pick-up basketball. The paramedics had documented a rapid dysrhythmia that resolved spontaneously. The EDP noted an epsilon wave on the electrocardiogram (ECG). The EDP forwarded the ECG to a pediatric cardiologist for a second opinion. The pediatric cardiologist highlighted the abnormality on the ECG and documented the possibility of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD). There was no direct communication between the physicians. The pediatric cardiologist intended to send a report to the EDP, but it was sent to a different physician with the same surname. The patient’s family physician never received a report of the ECG.

A year later, the patient suffered sudden death playing high school basketball. The autopsy revealed that she had ARVD. The lessons learned are all directly related to communication errors. There was no direct communication between the EDP and the pediatric cardiologist; as a result, the pediatric cardiologist did not communicate the possibility of a serious medical condition to the EDP, and no one arranged follow-up for a potentially dangerous medical condition. The EDP did not follow-up because he or she received no communication on the concerning ECG in this patient with true syncope and documentation of a rhythm disturbance.

HITECH Act

The HITECH Act was signed into law in February 2009 (HITECH Act, 42 U.S.C. & 300jj-11). Its purpose is to promote the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology in healthcare. The HITECH Act includes incentives for healthcare providers to accelerate adoption of the EMR among providers. Importantly, the HITECH Act gives the government more bite in its ability to prosecute healthcare providers who violate the Act. The Act is a powerful tool for attorneys to use when requesting an individual’s medical records. The Act directs healthcare providers to provide the requested information within a short period of time and at a reasonable cost.

Conclusion

Healthcare providers must understand who is responsible for documentation, what is important to document, when to document, how to document, who owns the medical record, the impact of changing to electronic medical records, problems and pitfalls when using the medical record, and how the HITECH Act impacts healthcare providers and health information technology. Healthcare providers must implement practices and policies that will meet all the documentation policies outlined in this article.

References

Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, et al. Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:1628-1638.

Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA. 2005;293:565-571.

Paterick TJ, Carson GV, Allen MC, Paterick TE. Medical informed consent: general considerations for physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:313-319.

Rodwin MA. The case for public ownership of patient data. JAMA. 2009;302:86-88.

Singh H, Thomas EJ, Sittig DF, Wilson L, Espadas D, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Notification of abnormal lab test results in an electronic medical record: do any safety concerns remain? Am J Med. 2010;123:238-244.

Topics

Risk Management

People Management

Related

AI Doesn’t Reduce Work—It Intensifies ItManage Your AI Investments Like a PortfolioWhy Training Employees Pays Off TwiceRecommended Reading

Operations and Policy

AI Doesn’t Reduce Work—It Intensifies It

Operations and Policy

Manage Your AI Investments Like a Portfolio

Operations and Policy

Why Training Employees Pays Off Twice