Abstract:

Outpatient practices are evolving into nontraditional models of care in an effort to maximize efficiency and patient volume. This has led to team-based models and the integration of telehealth and virtual visits. As patients now receive medical care from multiple sources and providers, the authors surveyed 796 patients’ preferences when receiving their care. Results indicate that most patients over age 65 prefer provider consistency and in-person medical care. Convenience is a preference for patients with higher household incomes.

An aging population and the increasing complexity of integrated chronic disease management have increased the need for primary care providers.(1) To meet this increased need, traditional models of care are being challenged.

Integrated delivery systems have responded with the evolution to team-based care and the emergence of novel practice models such as increased use of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) as well as increased use of technology in the form of virtual visits.(1-3) These new models are intended to improve access, decrease costs, and improve quality, but their effect on patient satisfaction is unknown.

Team-Based And Continuity of Care

Team-based care, defined as care provided by more than one provider in a collaborative fashion, was introduced to healthcare with the goal of decreasing provider burnout, improving quality, and decreasing costs.(4) Team-based care has been shown to improve hypertensive, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease outcomes in clinical studies,(5,6) however, the realized benefits have been otherwise inconsistent. The care model also has been shown to increase costs and can have a negative financial impact in fee-for-service environments.(6)

Continuity of care can be adversely affected when patients are managed by multiple providers, which can negatively affect clinical outcomes. Studies have shown continuity of care can decrease mortality and overuse of procedures and reduce hospitalization in longitudinal primary care settings.(7-9) Relatedly, comprehensive care models, in which physicians care for their patients in both outpatient and inpatient environments, have been shown to decrease hospitalizations and improve patient experience.(9) General provider consistency also has been associated with improved patient satisfaction and medical compliance.(10,11)

A systemic review addressing patient satisfaction with team-based care versus standard treatment showed inconsistent data with either a positive relationship between team-based care and patient satisfaction or no relationship.(12) Given current healthcare system practice trends toward team-based care models in the context of inconsistent evidence, we sought to investigate patient preferences regarding team-based care.

Methods

We distributed a 13-question survey to all patients in the Division of Community Internal Medicine outpatient clinic of Mayo Clinic Arizona over a six-week period from January 29, 2018, to March 9, 2018. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that the study was IRB-exempt as an anonymous survey. Thus, consent for participation was not obtained.

Mayo Clinic Arizona is located in metropolitan Phoenix-Scottsdale and provides longitudinal primary care.

The Division of Community Internal Medicine comprises about 25 providers, six of whom are PAs or NPs. The providers are all primarily outpatient providers, using a Mayo Clinic hospitalist division for inpatient care. The providers are divided into three teams of 7–8 providers. When patients are unable to see their assigned provider, they usually are seen by a provider on the same team to promote familiarity and continuity. Additionally, the physicians staff an acute care clinic with residents in a rotating fashion. NPs and PAs support the physician practice panels, but they also have slightly smaller patient panels of their own.

It should be noted that Mayo Clinic tends to attract relatively medically complex patients, and some patients have an additional primary care provider elsewhere. Internal medicine residents also see patients in CIM, but they were excluded from this study.

In all, 1,731 eligible patients received surveys; 796 surveys

were completed. The survey was anonymous with no patient identifiers. There were no exclusion criteria, and the survey was English language only. The optional surveys were handed to patients at the beginning of their appointments; anonymous collection boxes were placed at the nursing station located outside the exam rooms.

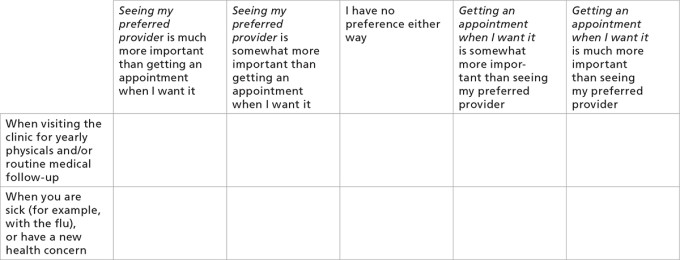

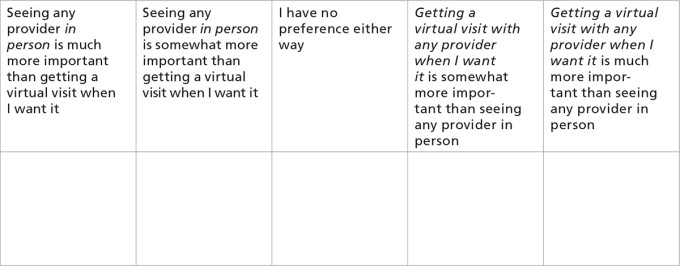

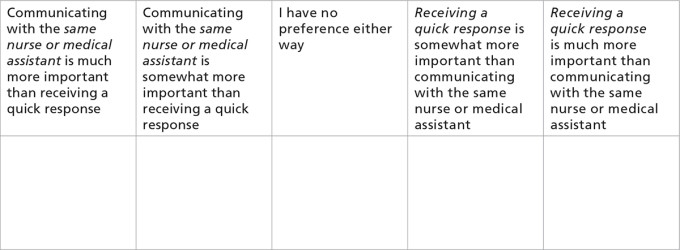

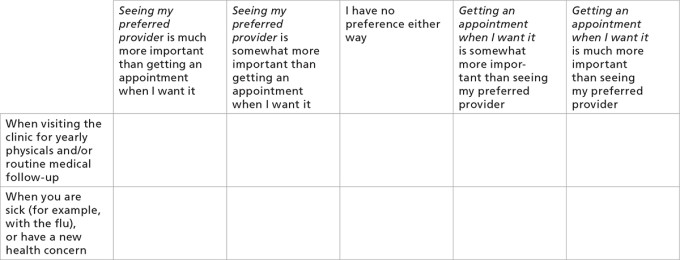

Four discrete choice experiment scenarios were used to assess patients’ preferences: 1) when visiting the clinic for yearly physicals and/or routine medical follow up; 2) when sick (for example, with the flu) or have a new health concern; 3) virtual visits vs. face-to-face; and 4) when communicating with nurses and medical assistants. Virtual visits were intended to include Internet-based encounters, such as the use of messaging and video.

For each scenario, the patient was to select among five choices to express preference and importance. The level of importance could be expressed as “much more important,” “somewhat more important,” and “no preference.”

The survey included questions regarding demographics such as age, gender, education level, income, age of children at home, time as a patient at the Mayo Clinic, primary provider (physician vs. NP or PA), and primary provider preference (medical doctor or doctor of osteopathic medicine vs. NP or PA).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize outpatient practice model survey responses. A chi-square test was used for categorical variables and Fisher’s exact test was used when appropriate. Differences between age groups were determined by Pearson chi-square.

P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). The Cochran Armitage test was used to assess the association between age and responses for annual visits and virtual visits.

Results

Males and females were well-represented among survey respondents, most of whom were older than 65, with no significant differences of preferences between them. Most of the survey respondents reported an annual household income of more than $100,000, and nearly all reported at least some college education. Most of the patients had been at Mayo Clinic for more than five years, and the overwhelming majority were assigned to a MD or DO for primary care as opposed to a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. See Table 1 for a detailed breakdown of patient demographics.

Age and annual household income were significant factors in patients’ preferences. Regarding annual exams, 84.5 percent of patients younger than 65 preferred seeing their regular provider while 90.6 percent of those older than 65 felt the same (p<0.05) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Seeing regular provider vs. timely appointment (p < 0.05)

When further dissecting and comparing age groups — younger than 35, 35–50, 51–64, and 65 and older — there were significant differences among the groups, with those preferring to see the provider increasing with age (53.3 percent, 57.5 percent, 69.5 percent, 76.5 percent respectively; p <0.05).

As for acute visits, 41.7 percent of those aged 65 and older preferred their regular provider while 41.5 percent of those younger than 65 preferred an appointment when they wanted it (p = 0.7949).

Regarding virtual visits, 71.7 percent aged 65 years and older preferred face-to-face visits, while 53.4 percent younger than 65 preferred the same (p < 0.05) (see Figure 2). The Cochran Armitage test for trend revealed an increased patient preference for virtual visits (Z = 5.108, p = <0.0001) as the probability of being younger than 65 increased. Similarly, for annual visits, preference for provider consistency increases as the probability of those 65 and older increases (Z = 3.06, p = 0.001).

Figure 2: Preferred face-to-face visit

When communicating with nurses and medical assistants, of total patients answering age demographics, 32.5 percent preferred the same person while 48.4 percent preferred a quick response (p < 0.05).

Variations among annual household incomes were perhaps more stark: 55.4 percent of those with annual household incomes greater than $100,000 were interested in getting prompt nursing replies rather than speaking with the same person, while 37.5 percent of those with annual earnings less than $100,000 preferred the same (p <0.05). Of those with annual household incomes greater than $250,000, 28.6 percent would prefer a prompt virtual visit as opposed to face-to-face visits (p <0.05), while 12.8 percent of those earning less than $100,000 annually said they would choose the same (p = 0.0026) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Preferred prompt virtual visit

Discussion

This study shows that patients fundamentally still value the doctor-patient relationship, particularly for yearly physical examinations. This is consistent with findings in a previous study by Pereira and Pearson.(10) However, this is discordant from review findings by Wen and Schulan, which cited studies suggesting that patients had higher satisfaction with team-based care.(12)

There are statistically significant differences between age groups above and below age 65, but more than 80 percent of patients surveyed preferred seeing their regular provider for yearly exams. In contrast, the doctor-patient relationship appeared to be less important for acute visits, as there was no significant difference between choice of consistent provider versus a timely appointment with any provider.

As with other studies, convenience seems to be more important for some patients when accessing the medical system, including telehealth, for acute problems.(13,14) Virtual visits, while potentially a popular and cost-effective model that also improves access, were not uniformly preferred by patients in our study. Those 65 or older were the least likely to choose this option, but there was relative popularity among those patients aged 35–50. Potential reasons for the differences between the age groups could be understanding of or comfort with technology, preference of visit type because of constraints of time, or different values between generations and age groups.

Virtual visits also were more popular among those with household incomes greater than $250,000 and those with higher education levels. This could be secondary to time constraints on those with higher wage positions, comfort with or knowledge of technology between higher and lower educated groups, or possible value differences between higher and lower income and education groups.

This study has some limitations. This is a single-center study conducted on a relatively homogenous patient population. The survey was given only in English, lending to possible misunderstanding by those who do not understand English or for whom English is not a primary language. However, the difference in survey results offered in other languages would presumably be small. English-only surveys were chosen because of the low number of non-English speaking patients in the clinic.

Ethnicity was not queried in the demographic information and may lend to differences in answers among ethnic groups; therefore, generalizability of this study to institutions with higher racial and ethnic patient heterogeneity may be inappropriate. Additionally, there were some unanswered demographic questions. Finally, some discrete choice experiment responses were discarded because the answers were not interpretable (i.e., the respondent checked two or more responses).

Nevertheless, this information can provide a direction for both large integrated delivery systems and small medical practices looking to optimize patient experience. Overall, provider consistency, in the right setting, was highly preferred by those studied. Aiming to increase this experience for patients would seem to lead to higher satisfaction for institutions that perform a significant number of annual exams.

Increased team-based care, expressed by patients as getting any provider in a timely manner, would be supported for institutions and practices with higher acute-based visits. A balanced approach of offering both provider consistency and timely appointments with any provider would be a benefit for institutions with the means and appropriate patient appointment type.

If a system or clinic has a large number of patients in the 35–50 age group, higher education, or household income greater than $250,000, offering virtual visits could benefit patients. This study could be duplicated at institutions where demographics differ from those in this study to better relate to local preferences.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study negatively supports the use of team-based care, favors the use of consistent providers in annual exams, but supports the use of team-based care for acute issues. With the right patient demographics, virtual visits could be offered and preferred by some patients.

References

Xue Y, Goodwin JS, Adhikari D, Raji MA, Kuo YF. Trends in Primary Care Provision to Medicare Beneficiaries by Physicians, Nurse Practitioners, or Physician Assistants: 2008-2014. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(4):256-63. doi:10.1177/2150131917736634

Auerbach DI. Will the NP Workforce Grow in the Future? New Forecasts and Implications for Healthcare Delivery. Medical Care. 2012;50(7):606-10.

McGrail KM, Ahuja MA, Leaver CA. Virtual Visits and Patient-Centered Care: Results of a Patient Survey and Observational Study. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(5):e177. Published 2017 May 26. doi:10.2196/jmir.7374

Zomorodi, M. Exploring New Paradigms for Team-Based Care. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2018; 79(4):219-22.

Proia KK, Thota AB, Njie GJ, et al. Team-based Care and Improved Blood Pressure Control: A Community Guide Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(1):86–99. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.004

Kottke TE, Maciosek MV, Huebsch JA, et al. The Financial Impact of Team-Based Care on Primary Care. Am J Manag Care. 2016 Aug 1;22(8):e283-6.

Maarsingh OR, Henry Y, van de Ven PM, Deeg DJ. Continuity of Care in Primary Care and Association with Survival in Older People: A 17-Year

Prospective Cohort Study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(649):e531-e39. doi:10.3399/bjgp16X686101Romano MJ, Segal JB, Pollack CE. The Association Between Continuity of Care and the Overuse of Medical Procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1148-54. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1340

Tingley K. Trying to Put a Value on the Doctor-Patient Relationship. The New York Times Magazine. May 2018.

Pereira AG, Pearson SD. Patient Attitudes Toward Continuity of Care. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(8):909-12. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.8.909

Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patients’ Satisfaction and Reported Acceptance of Advice in General Practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25(157):558-66.

Wen J, Schulman KA. Can Team-Based Care Improve Patient Satisfaction? A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e100603. Published 2014 Jul 11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100603

Polinski JM, Barker T, Gagliano N, Sussman A, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. Patients’ Satisfaction with and Preference for Telehealth Visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):269-75. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3489-x

Coster JE, Turner JK, Bradbury D, Cantrell A. Why Do People Choose Emergency and Urgent Care Services? A Rapid Review Utilizing a Systematic Literature Search and Narrative Synthesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(9):1137-49. doi:10.1111/acem.13220

Survey

The outpatient primary care practice at Mayo Clinic is interested in your opinions about access to medical providers. We are always working to meet our patients’ needs and enhance our patients’ experience. Thank you for your participation in this anonymous survey.

What is your age?

Under 35

35–50

51–64

65 or older

What is your gender?

Female

Male

Prefer to self-describe ________________________________

Prefer not to answer

For how many years have you been seen in Mayo Clinic Primary Care (Family Medicine or Internal Medicine)?

Less than 1 year

1–5 years

More than 5 years

Which best describes your main primary care provider? This is the provider assigned to manage or oversee all of your care at Mayo Clinic Primary Care.

Medical Doctor (MD) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO)

Nurse Practitioner or Physician Assistant

I don’t know

Which type of healthcare provider do you prefer to manage or oversee your primary care?

Medical Doctor (MD) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO)

Nurse Practitioner or Physician Assistant

No preference

When making appointments, sometimes patients need to choose between getting an appointment at a time that is convenient for them and seeing their preferred primary care provider. Which best describes your preference in the following two scenarios? Please choose one box for each scenario.

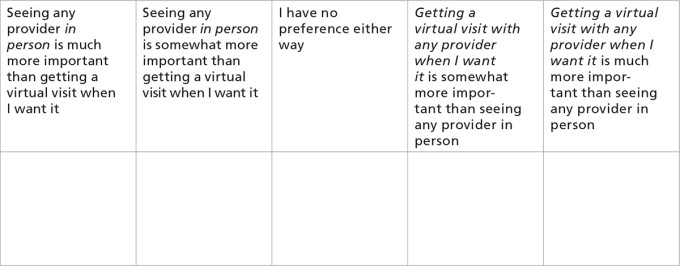

Virtual visits are computer- or phone-based patient interactions with a primary care provider. Mayo Clinic may have them available in the future. Which best describes your preference regarding virtual visits with any primary care provider versus face-to-face visit with any primary care provider for urgent healthcare concerns? Choose one box.

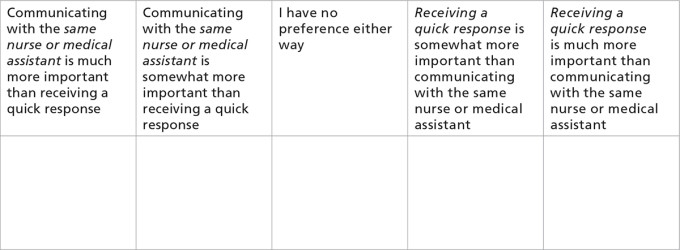

Patients can often have their needs met (medication refills, paperwork, and appointment requests, etc.) through a phone call to their main primary care provider’s nurses or medical assistants. Which best describes your preference regarding communication with nurses and medical assistants? Choose one box.

What is your annual household income?

Less than $50,000

$50,000–$99,999

$100,000–$250,000

More than $250,000

Prefer not to answer

What is your current marital status?

Single, never married

Married or domestic partnership

Divorced

Separated

Prefer not to answer

Do you have children under the age of 18 at home?

Yes

No

What is your highest level of completed education?

High school

Some college or associate’s degree

Bachelor’s degree

Master’s degree

Professional degree (example MD, JD)

Doctorate degree

Prefer not to answer

Topics

Quality Improvement

Working with and Through Others

Related

Applying Cross-Functional Team Methodology in Healthcare: Critical Considerations from Lived ExperienceHuman Resources: Motivation and Employee RetentionDoes Your C-Suite Really Operate as a Team?